'A powerful force of social cohesion' - The Red Lion, West Bromwich

The Black Country institution's stain glass windows retell the fate of the diaspora arriving after Indian partitioned in 1947

Disclaimer: this post mentions beer and pubs frequently. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse. It also features descriptions of alcoholism as well as racism.

A lot of people have signed up to the free weekly email recently and there’s a question of how to support the work I put into these posts financially. I publish them to promote the book so please pre-order Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here and/or donate £3 here.

One of the reasons why I’m so excited for my book to be published is because it’s going to open up a range of different experiences to people who may even consider themselves experts on desi pubs.

Last week I spoke to pub-lover Nina Robinson who, having grown up with Punjabi parents in the Midlands, knows her way around a mixed grill. She couldn’t believe a Nepalese-run pub in Bristol (Fishponds Tap) I recommended was serving such great food. It was great to receive a text from her saying the place was buzzing and lots of people were ordering curries - when I first visited the business was just taking off.

As you can imagine this knowledge of mine has been acquired by visiting many desi pubs around the country but I still am taken aback when I discover new ones because they usually have an enthralling personal story combined with great food and interesting customers.

I also think I’m continually being flummoxed because there’s still a lack of media coverage - although shout outs to Grayson Perry and Jay Rayner - so it feels like I’m entering into the unknown. I also have to admit I tend to err towards negativity - I like being surprised - but I‘m massively guilty of judging pubs by their exteriors.

If you want to know more about Desi pubs this book is coming in May.@jayrayner1 Great work, Jay. You’ll soon be able to find more around the country when my book comes out https://t.co/qA0lAIA4dUdavidjesudason@masto.ai #he/him @DavidJesudasonThis includes large establishments with car parks - outside of expensive metropolitan areas (ie London) where rents are cheaper it makes sense to have both of these things. I think this prejudice comes from growing up in a car-dominated market town where the worst pubs had parking spaces and microwaved food. Actually, I don’t think I had a properly cooked meal in a pub until relatively recently - another reason why I wish I had desi fare in boozers growing up.

And so to the Red Lion in West Bromwich, recently visited by Grayson Perry (full disclosure: they asked me to appear on the episode but then ghosted me) and with a rich history: since 1997 it took over a white space and then created a popular hub for desis.

The Red Lion’s big surprise is the custodian, Satnam Purewal, the son of original publican Jeet, who is a forward-thinking trailblazer and has shaped the pub to fit his personality. Being a sociology and psychology teacher he’s, as you’d imagine, an articulate advocate of the power of desi pubs. (“Pubs create social cohesion,” he told me. “And that’s the best thing about pubs.”)

But he also has created a modern, family and female-friendly pub. The novel features include a retractable roof, a quiet room suitable for children with autism and table service, which was brought in during the Pandemic but has ensured women avoid “the male gaze” of bar flies. I go into great detail in the book about how refreshing this approach is.

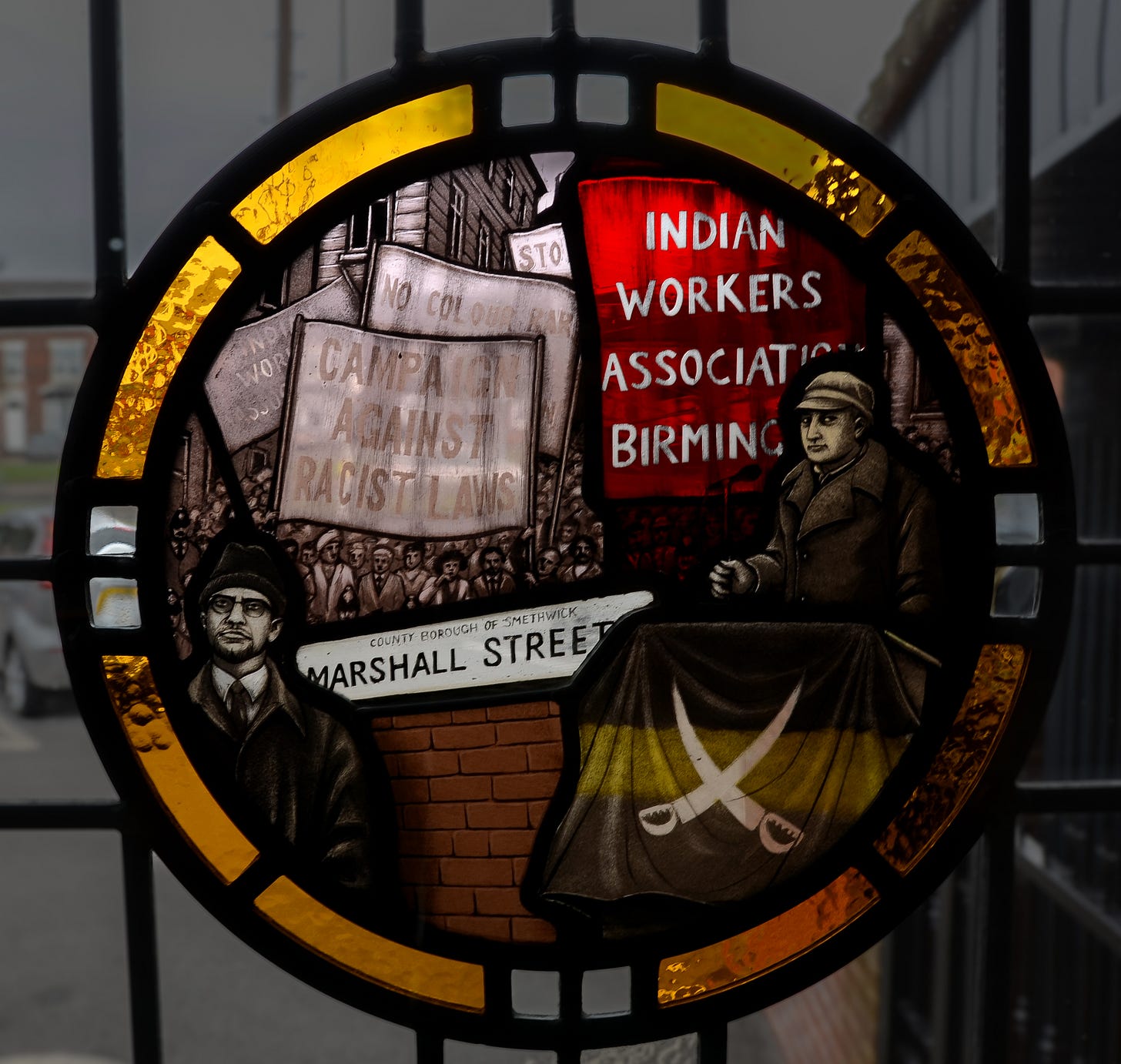

But Purewal has kept the historic narrative and today I want to show you the Red Lion’s four stained glass windows which tell an important story of how the Indian diaspora changed British life. They were created by Steven Cartwright after he was commissioned by Creative Black Country who ordered them to commemorate a guidebook to desi pubs in the area.

Strangers on a train

My paternal family’s voyage from India has never been told. My Dad was born in Singapore and liked the idea of being British, an identity he forged mainly because his father would beat him if he spoke in an Indian (or Malay) accent.

Surprisingly, when he retired to Borneo he would say “no, lah!” to me despite this being a total affectation but still the backstory was never explained. Consequently, I have no idea where he came from in India and when asked he would raise his voice and just say he was British.

My dad was also an alcoholic and I don’t want to excuse his actions but I think one of the reasons why he was such a mess as a person is he never had a truthful personal story - which led me to live a very confused life. Did he come from India? Did I come from India? What do I say when racists tell me to go back to India?

In Smethwick and West Brom it was obvious where the diaspora came from and what their mission was. Punjab. Here for a better life. Dalwinder Singh who runs another excellent desi pub, The Island Inn in West Brom, summed it up: “I came here and I couldn’t speak English.” Now look at him. His punters love him. His son runs a thriving pub in Walsall.

The glass shows how India was being partitioned and this led to huge amounts of violence between different religions. The bloodshed was not something they left behind in India, though.

‘Shitty jobs’

When I researched the life of anti-racist campaigner Avtar Jouhl Singh, who arrived in Smethwick on February 4, 1958, it was by listening to tape recordings he kindly lent me. The time I spent hearing his unique story were some of the most privileged hours of my life but although his tone was calm, his plight, like so many people who worked in Smethwick’s foundries, was brutal and sometimes even deadly.

Laundry black from smog. Twenty four to a house. Warming curry on casting. “Hard, hot, shitty jobs for Black workers.” Through these tapes Jouhl was able to give illiterate workers a voice - he was the only one educated among them. The Bir-Mid chain of foundries were Victorian factories with no ventilation where the Indian diaspora were paid less than their white counterparts but expected to do the hot “donkey work”.

Work hard. Send money. New life.

Mild at heart

On the right, holding a hand of cards, is Jeet, founder of the Red Lion. He’s drinking a pint of Mild which was said to unblock the congested chests of foundry workers. “They used to get all this rubbish on their chest,” Purewal says. “Because Mild was a very weak beer it would clear out all this rubbish.”

It was Mitchell & Butlers’ or Ansells’ Mild. Today the former is still drunk by older desis and is contract brewed by Molson Coors. At the Blue Gates, the landlord Jat tells me it’s the second most popular drink he serves (Carling is No 1) and he sells it for £2.50 a pint - cheapest pint outside of a Spoons, surely? At the Red Lion they sell Banks’ Mild.

“Not many youngsters drink it now,” Purewal says. “But if we get people visiting from London who lived in the Midlands and they see the [Banks’] Mild on the tap they go ‘whoa! I’ve got to have one of those!’ It’s nostalgia for people who live elsewhere.”

The pints of Mild were drunk at lunchtimes too by the desi foundry workers. This wasn’t leisure time, really, because they had to neck the drinks and then rush back to work - quenching their thirst after being in furnaces. Landlords, like Suki in the Vine (best friends with Jeet and near to the Red Lion) started their pub life by serving foundry workers and they would pour the pints ready for them and leave them on the bar.

Colour bar

Jouhl (right) is most famous for introducing Malcolm X, to Marshall Street and the segregated pub, the Blue Gates - which is, as mentioned, now run by Jat. Nine days after leaving Smethwick, on February 21, 1965, the US civil rights leader is shot dead as his pregnant wife and his daughters take cover in Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom.

The Smethwick visit gained national newspaper coverage but more importantly highlighted the plight of the diaspora around the country. It wasn’t just the Midlands that were racist in the early 1960s. And Jouhl drew Malcolm X to the area due to his work fighting the colour bar in the town’s pubs, factories and shops.

Mitchell & Butler may have brewed Mild but the landlords of the town didn’t want to serve it to non-white customers. This is what Jouhl said about his first visit to a pub:

I opened the door. And there were all white men. I asked why and they said, ‘Gaffer [the landlord] doesn’t let us drink in that room,’ and we were allowed to only go in one smoke room and one public bar. I asked why and was told, ‘The gaffer says we talk very loudly and white people don’t like us talking very loudly. And when we talk in Punjabi the white people complain that we are talking about them in our language.’ This was just the excuse, because in real terms it was the colour bar operating, and it was in every public bar in Smethwick and Handsworth.

Johul wasn’t cowed by this segregation and he would get white students to buy him beers in bars Black and Brown customers were banned from. When he was noticed he would be ejected, giving him evidence to use against these racist landlords when their licences came up for renewal.

Purewal says the window is a recognition of all the racism the diaspora put up with when they came here. It’s also one of two memorials commemorating Malcolm X’s visit - the other is a blue plaque in Marshall Street that stands near a desi pub called the Ivy Bush run by Lakhi Singh.

Without Jouhl, West Brom and Smethwick wouldn’t be post-racism as the diverse clientele of its desi pubs prove. Without Jouhl racist landlords would be serving racism customers. Without Jouhl desi pubs wouldn’t be a cultural phenomenon. Without Jouhl my book wouldn’t exist.

Avtar Jouhl Singh, anti-racist campaigner, trade unionist and lecturer, born 2 November 1937; died 8 October 2022.