A visit to a country pub

When a black Londoner took a walk in the countryside with friends she was confronted with hate and a pub landlord who ignored her

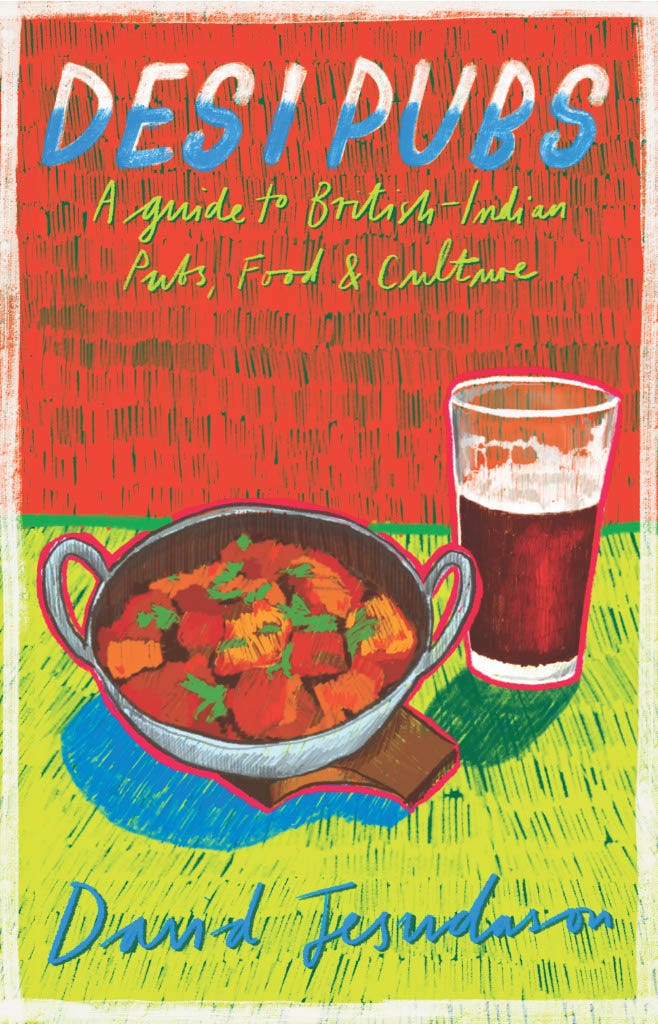

This article took a lot of research to put together. Please donate as much as you can to my Ko-Fi here to support it! If you’ve not done so already please buy Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here - hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”.

If you’re looking for information on BrewDog Waterloo this link will help.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

I am a journalist who covers race issues for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

This is how Melba Wilson navigated rural racism. She was born in Virginia in 1947, grew up in Texas and came to London, where she lives today, in 1977.

She’s a very educated black woman who had to endure a shocking ordeal that shows how daunting venturing out of a urban area can be for anyone who isn’t white.

Melba’s recollection is one that I empathise with having grown up in a market town in this country and been subjected to a lot of abuse whenever I venture into the countryside - in fact I’ve written about rural racism here, here, here and here.

It’s a little vignette into how the countryside was full of prejudice in a time - the New Labour years - that’s often cited (by white people) as being an era when Britain was more celebratory of multiculturalism than now.

“Over the years as a black person your antenna goes up and you have to steel yourself to walk through the pub door and just get on with it. I was so shocked by this incident - it was about 20 years ago - and it still rankles when I think about it.”

Melba Wilson is telling me about her experience of visiting a country pub - as she calls it - in the early 2000s with a bunch of friends.

About 20 or 15 years ago (she can’t remember the exact date) they were walking from Winchester, Hampshire along the Ridgeway National Trail in a group of eight.

She was the only black person in the group but they were long-time friends whom she felt comfortable with and they were celebrating one of the walker’s significant birthdays - a 50th or 60th. They were all fit, accomplished walkers and hoping to cover 20 km in a day with a stopover in a pub that had rooms.

It was one of those classic British days of variable weather that probably contained all four seasons rotating on an hourly basis, Melba understatedly described it as “mixed”. In fact it was so mixed that the group had to use a haystack for shelter from a thunderstorm at the top of a hill.

“We were all looking forward to getting to this pub,” says Melba, “which was our kind of weigh station. It was one of those old English pubs with Tudor beams and we arrived late afternoon ready for a drink.

“People were ordering and trying to sort out where our rooms were. When I walked in [I saw] a group which I later realised were squaddies - there was an army base nearby - and I heard this singing [in a low voice].”

As mentioned Melba doesn’t recall the year this incident occurred nor the name of the pub but in many ways it doesn’t matter because what happened next could happen and can happen in any rural location. In the past and now.

“There was this guy,” she says, “singing: ‘Who let the nigger in the pub?’

“He was surrounded by his squaddie buddies, so I guess he felt emboldened to carry on. He stopped after a while, I went up to him and looked at him. He didn’t show any signs of remorse. The other customers weren’t treating him negatively - it was like they thought you could get away with saying that in a country pub if there was only one black person around.

“It was one of those incidents where you’re shocked that somebody is doing it and then you think ‘how am I going to challenge this?’ I said to my husband: ‘did you hear what he said?’ and I wanted to complain.”

Having experienced this kind of racism, where I’m also the only non-white in the room and no one jumps in to help I can tell you that it's a really difficult situation to navigate. You have to have some record of experiencing this incident if you want to take the legal route but you also don’t want it to totally occupy your leisure time.

It’s simply a nightmare and one which white people don’t ever have to navigate.

“I spoke to the landlord,” Melba says, “he shrugged a bit. I wasn’t left with a sense that he would do anything about it or even speak to the guy. He just said ‘some people are stupid’ And that was it.

“I’ve been in country pubs a lot as my husband is [white] British and we did go to the countryside a fair bit. There’s always that instance where you walk into a pub in the middle of the countryside where people turn and look. Some of that is because you’re a stranger in town but some of it is because you’re a black stranger in town.”

It’s interesting to see Melba deconstruct racism in this thoughtful way despite how traumatic this event was.

“I’m the interloper,” adds Melba. “I’m the black interloper. The attitude is like ‘if you don’t like it you shouldn’t be here’. My friends were appalled but at the end of the day ‘what are you gonna do?’

When Melba told me this I speculated that at the time - remember this is the noughties, the Tony Blair/Gordon Brown years - that she could have reported it as a hate crime and had a fair hearing. But when you’re in an unfamiliar place is that something you can feel confident about?

“We had to cover another 20 miles the next day. The options were limited. I felt angry but I put it behind me, which is what we tend to do when we encounter racism that overt.”

The incident continues to mar Melba’s experience of visiting the countryside and pubs because she loves walking and continues to do so in her local community.

“I still go to the countryside,” she tells me, “and I still go walking but I choose less and less to go walking in the English countryside because I just don’t want to have to deal with any kind of incident. The idea of visiting this kind of pub doesn’t appeal to me anymore.

“Years ago I believed in the goodness of people but now I’m more wary about where I spend my time and the people I choose to spend it with.”

The flipside of this is that London is one of the greenest cities in the world and Melba doesn’t necessarily need to take a train to savour nature. However, it does show how the countryside is daunting for walkers of colour and how we’ve still a country halved: town v country.

And with social-political issues, such as Brexit, the rise of the far-right and gentrification, I believe racism - overt or covert - has risen since the noughties.

In fact, around this time the incident happened I lived in a town surrounded by the Hertfordshire/Cambridgeshire countryside and found it navigable unlike when I had lived in semi-rural areas in the past.

“I love London,” Melba says. “You can experience racism in London but I like the fact it is diverse and for all the reasons that people love London. I don’t worry about being other too much because loads of people are other here.

“This area is quite gentrified but still has a good mix of people. I don’t feel like I stand out.”

Worst of all I don’t see why the likes of Melba should be out there challenging this racism head on. She’s done her bit and it’s time the countryside - and pubs within it - became less daunting places for non-white walkers.