A watershed moment for women in desi pubs

I’ll never experience the feeling British-Indian women have when entering a desi pub full of men. So it's time for a few different perspectives

Disclaimer: this post mentions beer and pubs frequently. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse. It also features descriptions of alcoholism as well as racism.

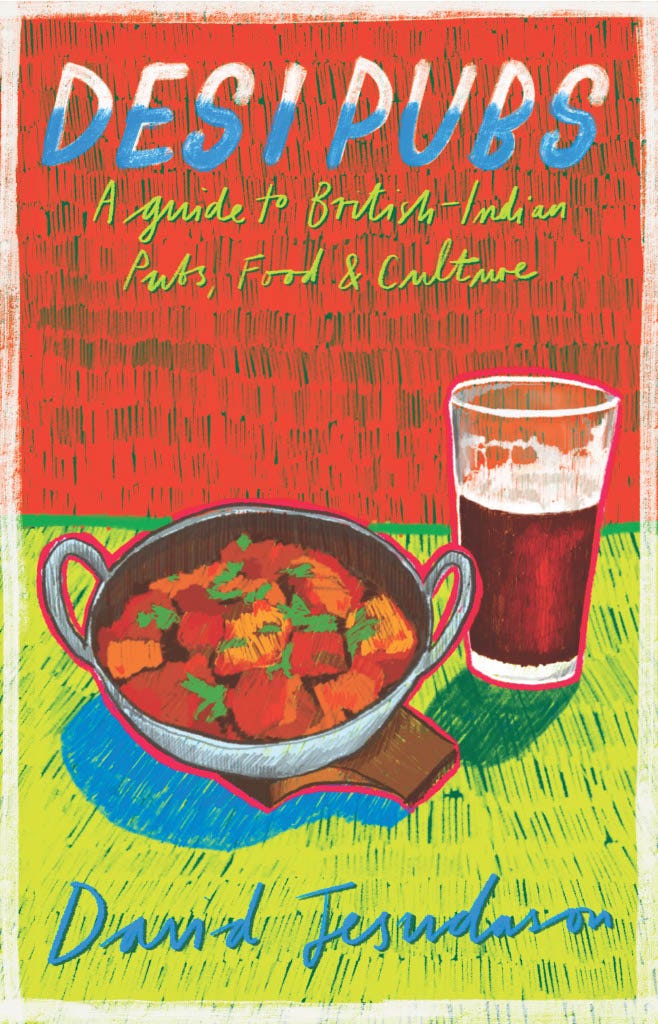

A lot of people have signed up to the free weekly email recently and there’s a question of how to support the work I put into these posts financially. I do them to promote the book so please pre-order Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here AND donate £3 here.

After interviewing more than a hundred British-Indian landlords for my book a few trends emerge.

The first is the aptness of the gendered term ‘landlords’ because as far as I know the only ‘landlady’ is Megha Khanna at the Gladstone, Borough, south London - compare this with all pubs nationally where one in three licensees are women. Despite this disparity, Meg throws herself into the role, and runs the bar with her brother Gaurav, but she’s also an outlier, as desi pubs were traditionally male spaces - something I want to explore this week.

The second is the number of Sikhs I speak to who originate from the Punjab region of India - it’s no surprise that ‘Singh’ is by far the most common name in my phone’s contact list. It’s a regular occurrence to see signs claiming to serve ‘authentic Punjabi cuisine’ and Sikh heroes plastered on the walls, as the Scotsman in Southall, west London exemplifies.

Without lapsing into stereotypes it’s fair to say that Punjabis have a strong drinking tradition and one which is easy to romanticise because they had the vim to carve out safe havens but this overlooks the social problems that can lead from it. Some even say that Punjabis - especially the men - are the loudest, most raucous of the Indian diaspora with women on the receiving end whenever this behaviour tips into excess.

In the era when British-Indians sought to find safe spaces to drink and set up their own pubs (1960s onwards) misogyny was rife and the first desi pubs weren’t an exception to this especially as they - like all drinking establishments then - weren’t family spaces.

Nowadays, of course, this has changed and the bad days of the uncles sitting at the bar passing judgement on women has been eradicated in the establishments I’ve visited. And there were exceptions like last week’s article on the Century Club proved.

However, when I put this to food writer Sejal Sukhadwala she says I’m not in the position to comment about desi pubs being female-friendly because I’ve never experienced the feeling she’s had when she’s entered a desi pub that has a majority male clientele. And, of course, she’s right.

So today I want to put a woman’s voice front and centre and that’s where Nina Robinson, Lecturer at Birmingham School of Media, comes in.

“My mum and dad had their 50th anniversary [at the Red Cow in Smethwick],” Nina tells me by Zoom - she’s recently had a knee operation, can’t walk and has been looking forward to this conversation as much as I have.

“This shows a change in Indian family life in Britain facilitated by these pubs. In the past the only Indian functions you would have were weddings and this was the only time families would get together. Now we have other celebrations.”

Nina feels this has been important in making family members have closer relationships with each other, especially for fathers who could be more emotionally distant. Just the fact that her parents saw her being more affectionate to her own children made a huge difference.

“This level of affection allowed us to have these celebrations,” she says. “I’ve done research into Punjabi ancestry and farmers, villagers never used to celebrate themselves or have these kinds of relationships with each other.

“The fact that women are now in these spaces means they can organise things in a different way that’s not centred around the Gurdwara and religion.”

Which is a huge contrast to Nina’s childhood where she grew up in a hard-drinking, male-dominated Punjabi family in the West Midlands where her dad worked in the iron foundries. There’s no point in romanticising their lifestyles as there were many alcohol-related deaths and substance abuse loomed large.

“My uncle was a video cameraman,” she says. “He did weddings and [his family] used to drink so much. His son died before him with liver failure. My uncle wore a Bagh-style turban and outwardly you would think it was quite religious but he drank a lot. The last time my Dad saw him at a wedding, he had drunk so much that he was on the floor.

“That was the indignity of that level of alcoholism.”

During these weddings, Nina tells me, the women would sit separately and have soft drinks on their table, while the men had bottles of spirits. This was at odds with women like her mother who yearned to join the men in the pub.

“She only recently started going,” Nina says. “Now you can’t bloody get her out of them!

“My mum’s mother-in-law, her bibi [respected woman], was the same. I have vivid memories of when my Grandad would come back from the pub and she would take his coat and smell it. These places would have a mystique to them because the women wouldn’t go.”

Nina says the earliest desi pubs in the West Midlands were the social clubs and her father, Balwinder, used to go to Samra in Walsall which opened late and was full of Punjabi men drinking hard. Her 71-year-old dad she says was a “determined drinker” but, luckily, knew when to stop.

“The women,” she says. “Would have bloody good fun, though. They’d be a samosa production line and at weddings I remember being stuffed in rooms with so much singing and dancing.

“The men were the boring ones drinking. We’d be having proper fun - telling lewd jokes and making up lewd rhymes.”

She admits that “Christmas was awful” because her brother refused to stop drinking even when he was vomiting black bile. And her brother-in-law is a functional alcoholic who also has problems with restraint even though his dad died early.

All this irresponsibility, you might think would make Nina a teetotaller but she now loves pubs, a romance which blossomed when she was a student in Oxford.

“I went to my first pub when I was doing my A Levels,” Nina tells me. “And I really had to research which pub to go to. I didn’t want to go to one where there might be trouble. It was in the white part of Walsall.

“Even now I have this fear factor. I need to know certain things about it before I go in. I make sure there’s no England fans and even football [on the TV]. These are always key factors of whether I go into that pub or not. First of all it’s my race and my experience of pubs being quite racist places.”

Then it’s whether the pubs are male spaces. The very first desi pub Nina went to was the Grove in Handsworth, before it was refurbished, in the early 2000s. It was a very different incarnation to modern desi pubs, such as the Soho Tavern or the Keg and Grill in Birmingham. She went with her brother who knew that she’d love the prawn pakoras served there and she’d just got her degree and was feeling “nothing could touch her”.

“It was all Punjabi men,” she says. “Growing up it was the same and it was the bastion of the men. And if you go into those environments as a female you’re either a whore or giving a bad reputation to your family.”

Nowadays, Nina feels most desi pubs have changed and become family-friendly especially the Grove which when it was refurbished became more inclusive.

“It became more acceptable for women to go there,” she says. “And the real turning point was when I thought it was OK for my kids to come to this pub on a Saturday night. The fact that I felt like I could do that in a really busy pub was a watershed moment.”

That’s not to say Nina isn’t aware of the struggle it was initially for men from the Indian diaspora to carve out safe spaces when they lived in a hostile country many years ago. Her family couldn’t walk in the street after Enoch Powell’s infamous Rivers of Blood speech and racial segregation was still rife.

In fact, she confirms her father was subject to a similar prejudiced act in this essay I wrote about anti-racist campaigner Avtar Jouhl Singh which I wasn’t able to confirm before publication. I wrote:

Jouhl also tells of non-white drinkers being given glasses with handles, presumably so white customers wouldn’t use the same vessels as them, but I am unable to corroborate this account. In any case, the segregation and abuse Jouhl and his flatmates faced was very real.

“[My father] went to the Belle Vue pub [in Birmingham],” she says. “It was white-owned and they used to go there all the time despite it being racist. They used to get a really bad vibe when they went in there and they used to give white people straight glasses and the Indians used to get the glasses with handles.”

This settles it. When I promote the book after it’s published I want to create some commemorative beer glasses without handles and explain the cultural significance of this move.

Recently I visited the Tap & Tandoor in Solihull which bills itself as an Indian gastropub and serves craft and cask beer alongside very high-end Indian dishes, which have a Tapas-like feel. It’s run by Ajay Kenth, while his wife Shivani owns a street food restaurant in Moseley called Zindiya.

Shivani has a hand in the pub business - there’s another Tap & Tandoor in Peterborough and one soon to open in Southampton. Apart from Meg in the Glad, I think she’s the nearest I’ve come to finding a desi pub ‘landlady’ on my recent travels. But like Meg, she’s involved in the operation of an establishment that is updating what we can expect from an Indian-run boozer.

What she tells me about old-style desi pubs, though, resonates with Nina’s experience with her father drinking in Spark Hill Social Club on Friday with other men despite it being next door to a community club the whole family went to.

“As a kid,” she tells me. “We couldn’t even go to the door to see our dads.”

Cutting out whole sections of family life from a pub is a very risky business model and it’s ironic that nearly every desi pub landlord I’ve spoken to took over a boozer that was failing. I can’t comment really on how much things have changed because of my male perspective but when I visited the Grove - the watershed pub mentioned by Nina - it seemed to have a very mixed demographic.

“The key,” Nina adds. “To unlock the desi pub success is how well they cater for women or how comfortable women feel there. What I want to see next is a Punjabi landlady. That’s the only way we’re going to have proper change.

“In [places] like the Copper Fox Grill [in Birmingham] there are women working as part of a husband/wife team. We need them stepping out of the back and really running these places.”

Meg, publican at the Gladstone, is currently in India visiting family but she’s able to speak to me on the phone between flights about how special it is to be a trailblazer, and possibly Britain’s first desi pub ‘landlady’ even though the term was unfamiliar to her at first.

“When I told my friends,” the 36-year-old says. “That I was taking over a pub. They were like ‘oh, my God, you’re going to be a landlady!’ but I didn’t even know what that meant. They were like ‘you’re going to be like Peggy Mitchell!’

“Now, it feels like trendsetting to be a young landlady, as well as an Indian landlady.”

Meg and Gaurav grew up in Zambia, in southern Africa, with a family with Punjabi roots and she describes her parents as open minded, so they didn’t have any objections to her running a pub. In fact, her words echo Nina’s especially with how the drinking culture has recently revolutionised - and not just for the diaspora but older Indians in India.

“On my mum’s side,” she says. “It’s pretty traditional but they’ve changed a lot. There was a time when the men would drink on Fridays and they would close the doors and be on their own. The women weren’t allowed to drink or even go into that room.

“Now that I work in a pub my uncles and aunts have become very open about drinking. They want to get their children involved more especially now they’re older. It’s interesting that you asked me about this because I’ve just been to my uncle’s place and we went out for dinner.

“We’re in Amritsar [a city in Punjab] and it was bring-your-own booze. My uncle bought me some wine and asked if my [female] cousins wanted to share it. They’ve modernised.”

I ask Meg if she found visiting any desi pubs, like the Prince of Wales in Southall, hostile and she says this wasn’t the case and nothing like pubs in Dartford, Kent where she has a flat. “People [in Dartford] do look at me in a strange way when I enter the pub. But I think that’s to do with being a woman going alone to a pub which is a completely different thing.”

The only difference Meg can see with her family now is over the issue of restraint.

“It’s not like a culture,” she concludes. “Where you get wasted and thrashed in front of your family. In some parts of Britain people get really merry with their mum or dad but it’s not like that in our culture. Even if they came to London to visit the pub - there’s still a line that we don’t cross.”

Next week I’ll either be delving deep into how the term ‘desi’ can be used or I’ll examine Handsworth Horticultural Club and its uplifting connection with the Grove.