Brockley Barge - how JD Wetherspoon broke its colour bar

The shocking tale of racial segregation operating in a London pub unchallenged

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

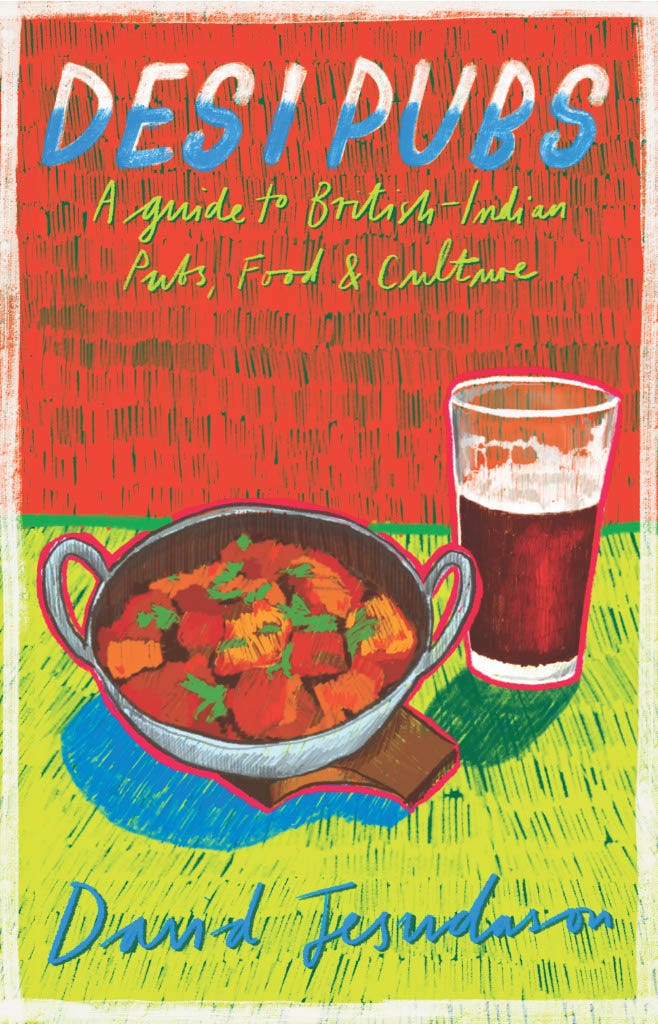

I’d like to thank everyone who has donated to my Ko-Fi here. If you’ve not done so already please pre-order Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here.

This article should be paid content. In fact, it was commissioned but I chose to withdraw it from the publication as they wanted to change it too much from the initial brief. There’s no bad feeling about this decision and sometimes you have to value a compelling story above financial concerns. But if you like it please pledge some funds here as it took a lot of time to put together.

Today’s article is a difficult read. It’s about a pub that was segregated while no one cared - apart from the people who had to be separated from other drinkers. It’s also about the type of pub that has been in the news recently - the kind that hangs Golliwogs, puts a sign outside warning those ‘offended’ to stay away and then claims it’s not racist. (Can we bin the word ‘offensive’? It’s more than ‘offensive’ when what’s being committed is a criminal act.)

But worst of all this is about a pub that remained segregated until the mid-1990s.

Today it’s part of the JD Wetherspoon chain, which is not known for its inclusion or diversity, but it’s worth considering its record dispassionately. And moving away from a discourse that ridicules the punters of such establishments - for example tweets that joke about the customers being ‘gammons’.

That’s not to say the argument against the way the chain operates isn’t compelling and the charge list includes the way its workers and suppliers are treated not to mention how much disinformation it displays against the EU - founder Tim Martin played a prominent part in using his venues to spread Leave campaign lies and propaganda. For some Pro-Europeans, Spoons is the byword for what is wrong with Broken Britain.

I don’t want to evangelise about the chain but I do want you to understand that this story wouldn’t have been able to be told without the steps it took when it acquired the pub and the access they gave me to interview staff and customers. I’m not saying that the pub I feature today is a utopia but it’s the most diverse pub in the area I live in and has a very community-minded landlord - he’s technically a manager, but he’s really a custodian.

So it’s Friday and it’s time to take an unexpected trip to the Barge.

“Here,” says Ken Jauval. “You had a white bar and you had a black bar.”

Jauval is talking about the Breakspeare Arms in Brockley, Lewisham in South East London, which closed around the mid-90s. He is part of a large community in the area with Caribbean origins - Saint Lucian in his case - and is with his friend Kilroy Gladstone, who came to Britain in 1957 from Jamaica. Unlike Gladstone, Jauval has a London accent as you’d expect from anyone who grew up in this country from the age of nine and is aged 60 (he told me he was “nearly 60" in August last year).

In fact, Jauval is a fast, excitable talker and when he recalls the Jamaican pubs in the area, such as the Golden Anchor in nearby Nunhead (the only one left with a Jamaican landlord, Lana) or the bars owned by Ivan ‘Leggie’ Legister and an elusive ‘African’ called Nelson, he becomes even more animated.

However, when he talks about the reception he received when he visited the Breakspeare Arms there’s more pauses as he considers his words carefully. “There was a problem,” he says and then laughs nervously. “There was a problem. There was a problem. I don’t know if you want to write about this: but they had a thing with white and blacks.

“It had a colour bar. It wasn’t acceptable to me but you played along with it.”

It was something that had to be accepted because Jauval remembers his dad not being served in the pubs in the area at all, such as the Brockley Jack – now a Greene King pub/theatre, which last time I went had a black bar manager. This discrimination he says was common in the area with the nearby Maypole (which is now flats by Brockley train station) also segregating on grounds of colour - and he believes it only really stopped when the Breakspeare Arms was reopened by JD Wetherspoon in 2000.

Jauval explains how the pub was divided into two and he would see his white school friends in the side that he wasn’t allowed in. What other locals tell me is that the Breakspeare Arms had an “Irish bar” and a “black bar” which was segregated to the point that the only people who could freely go between the two internally were staff as the bar was the only visible passage between them.

Hearing this information was gut-wrenching and the manager of the Barge today, Caesar Kimbirima, confirms it happened, going on to tell me that there even were separate toilets for white and black customers up to when the pub closed.

“The pub was divided,” Kimbirima (pictured) says. “There used to be a bar in the middle for whites and one for blacks - the same as the toilets as well. Their toilets were outside.”

After spending so much time looking at cases of the colour bar nationwide it appears that the worst modern case was in my eyeline the whole time - in fact, perversely, I remember going to the Barge one morning and writing the Wikipedia page on UK Racial Segregation on my laptop.

Ged Freel is a retired teacher originally from Newcastle who is spending some time reading his newspaper in the Barge before I interrupt him. His mother was Irish, he taught Primary school kids in Greenwich and bought a house here in 1984/1985 with a few other blokes - “We were old mates. And thought it would be cheaper to get a mortgage.”

Freel has the softest of North-East accents, having spent so long in London - he has strong roots here now as his grandkids go to the school that Jauval also attended. He, as you can imagine, doesn’t speak fondly of the pub when it was the Brakespeare Arms and although he’s the only white customer I’ve spoken to about the colour bar he’s quick to point out that his wife is black.

“They used to call it the black bar,” he says about the mid 1980s. “And the Irish bar. I used to come to the black bar. The Irish bar was really stiff and reserved - they used to come in ties and that sort of thing. This side of the bar [the black side] was [comparatively] like a lunatic asylum.

“We never came in here a lot because the Wickham Arms was more civilised in those days.”

(As a sidenote the nearby Wickham Arms was fun in the noughties but could be a bit loud when football was on. When I visited last summer it had changed so much that there was a play area for kiddies. Freel joked by saying in the 1980s “it had the more sophisticated Millwall supporter! It’s a contradiction in terms but in those days they were into football and not racist.”)

Freel also believes the colour bar at the Brakespeare may not have been deliberate “but it just became rigid with very few Irish guys going to the black bar and very few black guys going into the Irish bar”. When I ask him if black guys would get served in the Irish bar he does pause and say “I never saw it happen, actually”. He also can’t remember the separate toilets as it was so long ago.

The biggest problem Freel witnessed in those days were the fights. “I used to have an Australian neighbour - a big guy. He used to come in here and look for a fight.” I also ask him about the nearby Maypole and he says he never went into it out of principle because it was a “shithole” which eventually got closed down because of drug dealing.

In fact, a lot of the pubs that I speak about here had all sorts of criminality going on including murders. “There were stabbings,” confirms Kimbirima about the Brakespeare. And the way the area gentrified meant that one step was missed from all these boozers, as they turned from “rough” pubs into pricey gastro pubs. The only exception being the Brakespeare which lay shuttered for four years until it became part of the Spoons chain in October 18, 2000.

Because of this it’s rare to see groups of drinkers of colour in any pub apart from the Barge (or possibly the Brockley Jack).

Kimbirima is a remarkable man, so much so he was interviewed by the BBC about his transformation from being a child soldier in Angola to pulling pints in Brockley. He’s so full of life now and optimism that it really shows how strong humanity can be.

“My way to run a pub is to make everyone feel the same,” he tells me. “A lot of people who used to come here to fight stopped wanting to fight. I did this by treating them with respect and making them feel welcome.”

Kimbirima is telling me the steps he took to change the pub and, although he arrived in 2014, he’s uniquely placed to talk about its shocking history. He spoke to many of the locals about the colour bar and gained more intel from the first bar manager who had to take radical steps to make the pub safe and inclusive - barring scores of troublesome punters.

“I spoke to a lot of the [black] customers from the 1980s,” he tells me. “Sadly, a lot of them have passed away now. What they told me was they weren’t allowed in the white toilets or white bar. ‘That’s for whites, your bar is over there’ they would be told.”

You can see why Freel got the impression that it was divided out of customer choice, though, because the black bar was larger and sounds a lot more fun - a DJ would often play records, for example. But it was a colour bar nonetheless.

“When I came in 2014,” Kimbirima reveals. “On the second day, I noticed the pub was segregated - not because they were told to do this but this was the mentality of the customers. That’s when I started talking to people asking them why they sat on a particular side.”

Marchelle Moore is one of the staff members Kimbirima manages and she started working at the Barge in 2006. She confirms that it was very segregated. “You would have people of colour on one side,” she tells me. “And white people on the other side.”

The steps Kimbirima took to desegregate the pub were simple. He moved tables around especially if it were the ones that regulars used to like - “slowly, slowly” it started changing. “And now when you walk in you see a variety of people everywhere,” he concludes.

Moore confirms that this simple trick worked. “As the years have gone by,” she says. “It became more mixed. So it's now more a family-orientated pub with more of a mix of ages, colours and nationalities - and it’s just more relaxed. Before you’d come in and look around where to sit to not invade anyone’s space.”

The zero tolerance policy Kimbirima and his predecessors took to trouble-makers meant that the locals who came here for a drink got behind his approach. When he started in 2014 it had door staff - and I know this first hand as I drank here from about 2005, because I remember watching the cricket (the Ashes that year were memorable) when it was on free-to-air TV.

“I kept the door staff for three months,” he says. “Until I got to know the customers and area. There’s always the occasional argument but if you compare it to what it was like in the Breakspeare time it’s huge.

“I believe now a customer feels safe without the door staff. Now families come until 8pm.”

Kimbirima sometimes gets compliments for his approach but he’s keen to say it’s the JD Wetherspoons’ way of doing things and he’s just the manager. “It was a tough beginning,” he says about 2000.

“The mentality of the customers was that it was ‘still the Brakespeare’ where they were allowed to do what they want. We told them we have company policies in place and we don’t allow those things - the people who were barred tried to come back in but the staff knew a lot about them.”

Looking on Rightmove, a four-bedroom house in Brockley can sell for around £1.5m with the area being pitched (rightly) as leafy. The marketing bumf will also mention the good schools, coffee shops, gastro pubs and delis but you’ll never see a reference to the Brockley Barge - I mean, it’s a Spoons, right? But I hope this shows how it played its part in making this part of London safe, inclusive and family-friendly.

One of the reasons I was drawn to this story apart from its locality to me was because it shows how these type of pubs can offer social cohesion despite possessing a racist past. There’s plenty of stories like this in my new book - out in two weeks - praising desi landlords who acted like Caesar Kimbirima did. It’s not a glamorous job but it’s essential because they’re at the frontline fostering diversity - I think an academic calls it “the vanguard of multiculturalism”. Without them Britain really would be broken beyond repair.

https://twitter.com/DavidJesudason/status/1654088364503474176