I've come a long, long way - The Windmill, Croydon

Disclaimer: this post mentions beer and pubs frequently. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

You can pre-order Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here

I asked the opinion of a long-time admirer of this newsletter if switching to covering pubs and beer last week was too much of a change. She replied that it wasn’t as it’s still about identity and belonging. These two themes are always at the forefront in my writing and if I err please tell me!

I you need to know what a desi pub is please read this.

This year marks a milestone that I’m slightly embarrassed by. I was around 15 when I had my first pint and here I am 30 years - and many - hangovers later detailing pubs and beer in a (hopefully) responsible way. I’m not uncomfortable with the amount of alcohol I’ve drank in the subsequent three decades but I am conflicted about the age I was when I embarked on this boozy existence.

What’s funny is I didn’t even think it was that rare until I mentioned it in a story I filed and the editor said “you may want to explain how you came to be served at 15”. The answer is in the 1990s IDing was not yet prevalent and I don’t ever remember being declined service in this country (visits to America were different).

Drinking in the 90s, 00s, 10s and 20s has meant there’s some haunts that I’ve visited for a long time, like the pubs around Arsenal and Crouch End (Auld Triangle, Nicholas Nickleby) and Lewisham (the Talbot, Ravensbourne Arms). What these pubs have in common is they are all now, sadly, dead (although the Triangle appears to be returning in some form) but their atmosphere - or vibe if you like - lives on in my soul.

That sounds melodramatic but I can be whisked back to one of these ghost pubs in seconds by meeting an old friend, tasting a familiar beer or hearing a unique phrase. Their residual memory shouldn’t be a surprise as I’m sure we have a section of our brain for pubs in a similar way we do for other parts of culture, such as music.

On this subject, a psychologist I heard on the radio recently said we tend to remember songs we first heard in formative parts of our lives, such as when we moved to our first non-parental home. The same goes for pubs: I’m sure the ones you remember best were experienced when young, especially when you first felt ‘free’ from the folks.

Desi pubs, for South Asians, are no exception and many have departed with much sadness leaving us with a gap in our drinking lives. The first desi pub I visited frequently on my own (I think my dad took me to one in Pinner when I was younger than 15) was the Blue-Eyed Maid on Borough High Street. It’s now boarded up and Jay the landlord cannot be found - if you’re reading this, Jay, thank you! His army of brown door staff were an early example to me of brown empowerment.

Other desis (slang for British-Indians) have treasured memories of Glassy Junction and the Horseshoes in Southall - I’ll revisit both in later newsletters. While I think of Steve Collis, who I interviewed here about Old Monk rum; he has fond memories of two desi pubs that are now dead - The Alpine Horn in North London (demolished) and the Ballot Box in West London (worse than demolished, it’s a Wacky Warehouse).

Writing my book on desi pubs I’ve always been scared that a pub I feature will close and I’ll have to expunge all the information from the guidebook. It’s doubly bad as these are often pubs that have a working class demographic and the cost of living crisis is a wrecking ball to these communities. Luckily this hasn’t happened yet apart from the first desi pub I visited for the book which so happens to be the nearest to where I live (sigh).

This is the story of the Windmill in Croydon.

In 2011, Darshan Barot visited the Windmill, was greeted warmly by the punters and decided that being a pub landlord would give his family a better life. He was running a post office seven miles away in Coulsdon but he wanted a business he and his wife, Dipta, could run and, most importantly, stamp their distinct desi identity on.

The pub before Barot took over was described to me by former Croydon resident, Libby Bradshaw, as “not exactly rough, but not not rough”.

Dipta had worked at the Regis in Norbury - a desi club (now dead) - catering for Indian weddings that would’ve been hard work. The Barots are different to most desi landlords in that they are Gujarati (rather than Punjabi) so the food they had when growing up in Mumbai was mainly vegetarian. They’re also Hindu not Sikhs - this makes them outliers, as Sikhs from the Punjab set up the first desi pubs so that their community could have safe places to drink and play Bhangra music.

When they arrived in this country, though, Darshan’s uncles introduced him to non-veggie food.

“I don’t eat beef, though, because I’m a Hindu,” he says. “I must have only visited pubs twice before I came here [top the Windmill]. It was a recession and we were planning to buy a restaurant. We thought English people love curries and pubs are closing - so why not serve curries in a pub?”

Like most desi pubs, though, the dishes that were the most popular for his punters (he retained all the locals giving the pub a lovely Irish/Asian feel) were “non-traditional fare” - ie not Indian takeaway staples. The standouts were desi lamb and chicken kolhapuri (spiced and cooked with coconut).

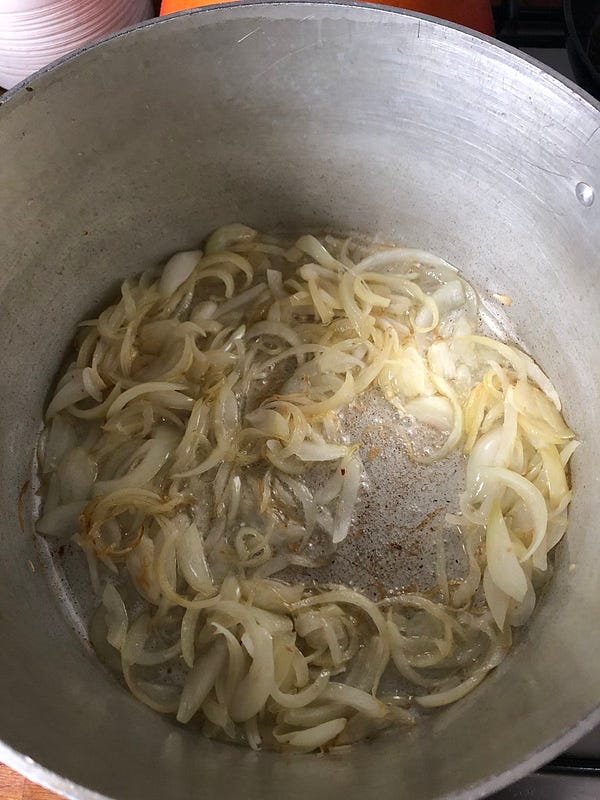

“Desi” when used in the context for a dish means it’s cooked home-style. This means it is cooked “bhuna” (one explanation is here) which was interpreted by my mother to mean slow cooking onions until they brown, using fried spices and then slow cooking meat. Whatever “bhuna” means here the curries always have a rich texture and tender meat. They’re my absolute favourite.

If you’re curious this is broadly the recipe I use.

Whatever the case these amazing dishes were served by Dipta through a hatch to the Windmill’s diverse crowd - during match days Crystal Palace fans would love coming here and would rub shoulders with the desis. You can even marvel at the “tapas”-style dishes here with this menu I found here and here.

Libby, who now runs the Twelve Taps in Whitstable, particularly enjoyed the food after the pub was transformed by Darshan (pictured below) as she lived round the corner and was really surprised by what they were serving.

“It always had a nice atmosphere [when they took over],” she says. “Even when there was football on the telly. It never was blokey, or a bit full-on. We’d have fresh pakoras while drinking beer - it was tapas-style and you could order little bits off the menu.

“I’d never had pakoras that fresh before - they were brilliant. It quickly became the favourite pub of a few people I knew. I went there with some Asian mates and I still associate this part of Croydon with Asian food, especially the curry house next to the Safari Cinema [possibly the Akash].”

It seems I’m not the only one who is whisked back to ghost pubs like the Windmill at a brief mention (I posted online I would be writing about it a few days ago) and Libby admits after seeing my post she couldn’t stop thinking about Dipta’s pakoras. It also made her miss what she lost - Whitstable doesn’t have a desi pub culture.

Croydon has a massive desi pub that still stands. The Crown and Pepper - the other side of the town to where the Windmill stood - was refurbished in lockdown and I have interviewed the owner, Raj, for my book. It serves Chinese food as well as Indian food, and adapted well to meet a changing clientele - I once worked for a few weeks in the office block opposite it a long time ago, which has recently been turned into what some describe as luxury flats.

“We opened here,” says Darshan. “Because it was heaving at the Crown. For the first one and half years here we didn’t do food as we wanted to get to know the customers first. We tried the chilli chicken and salt and pepper prawns and they loved it.”

The Crown is a sports bar-style desi pub (football and cricket are popular at desi pubs) and is aggressive on pricing - they try to steal the takeaway food crowd as well as people looking for a restaurant or gastro-pub dining experience. The lockdown meant Raj could pivot his business to a takeaway model and serve a wide area - he has a large kitchen.

The Windmill couldn’t make such a change because it's located in a residential area and as the hatch suggests is a home-style kitchen. The day I visited it was creaking to a conclusion with few beer options as a gas delivery hadn’t arrived. This did lead to some merriment, though, as a few of us decided to hit the African Guinness, including one guy who needed a painkiller after visiting the dentist.

I took some photos - noticed the for sale sign - and Darshan admitted at the end of the interview there were only a few days left of the pub.

Darshan’s plan when we last spoke was to open a desi pub in a village. This is a trend that I’ve seen elsewhere and I’ve even visited a pub in the Cotswolds run by Kyle Mahli, who is steeped in desi pub heritage. His father, Bera, runs the Red Cow in Smethwick, which I wrote about here.

Kyle, who is in his early 20s, told me proudly that he pulled his first pint when he was aged eight and is totally at ease in a pub where all his locals are white. He took over the Ivy Inn after the previous owners failed to make it a foodie destination and alienated their locals, who never felt welcome if they just fancied a pint.

I’ve also arranged to meet Mauli Dwivedi at the Brewers Inn in Cambridgeshire who told me over the phone that he even goes hunting for some of the food he serves. (To be honest I’m not sure if that is a desi pub as they mainly offer traditional food, but I’m willing to bend my argument for a good narrative!)

What all these desi publicans have is a sense of wanting more from pub life than competing with Indian takeaways and the various food outlets towns and cities offer. Put simply a village pub will give them a monopoly of decent Indian food even if that means they have taken a different course from desi trailblazers who first opened pubs to create safe spaces for their communities.

But that’s not to say they stay as white enclaves as Kyle discovered when people from Birmingham and London started driving to the Ivy Inn to experience a bit of village life. It was really nice, I have to admit, to sink a pint of UBU Purity on a warm autumn day, to the sound of birdsong. It’s difficult though as rural areas can often be hostile, as I write about here, so I guess that makes them trailblazers too.

Darshan and Dipta always have already been groundbreakers - as their regulars will attest - so the countryside could be a good fit.

The headline is from Saint Etienne’s Nothing Can Stop Us. The band’s Bob Stanley and Pete Wiggs were from Croydon.

It’s hard to predict what I fancy writing about next week but I may explore Southall and the oxymoronic notion of a white desi pub landlord.