Lucky number 6: how I became an author

I became a journalist in 2004 but I only gained agency a decade later

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse. There’s one mention of suicidal thoughts.

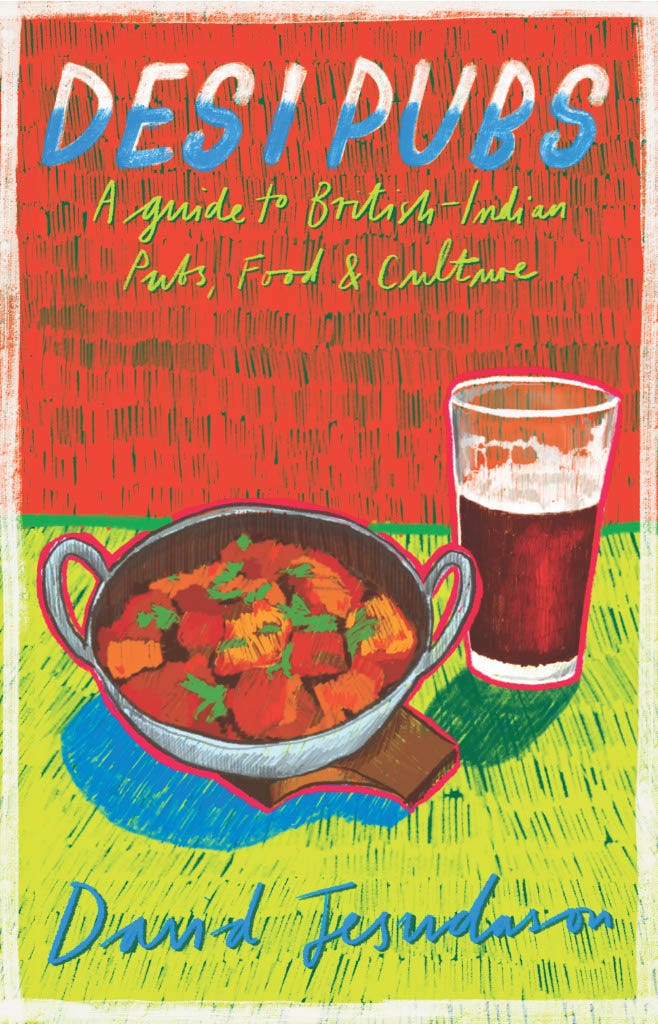

I’d like to thank everyone who has donated to my Ko-Fi here supporting independent writing. If you’ve not done so already please buy Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here.

My book’s out and being read! (Unless you’re someone who buys from Amazon, in which case you’re probably still waiting for it due to a delivery issue. It’s quicker and currently the same price if you buy it direct here.). So I’ve been busy but that’s not entirely the reason there was no email last week.

As you know this Substack comes out on a Friday but I was commissioned by Vittles which meant that two articles by me would’ve potentially arrived in your inbox at the same time. Instead I shunted this piece to this week and is being written as I fly to Prague (but edited afterwards with notes in italics) to give a speech at a brewers’ conference on diversity.

I don’t feel like an expert on this subject, or on many subjects to be honest, as I’ve always felt my job is to tell other people’s stories. Maybe I am “diverse” and that’s all that needs to qualify for such gigs - not just in colour because I am from a working class background with a mother who worked for the NHS all her life and a father who spent long periods unemployed. Note: the talk went well.

But, in many ways, this is what this article is about - my feeling that I’m not special despite evidence to the contrary - and I’m just a number. Especially because when I give presentations, similar to the one I will perform tomorrow, they’ve always gone well. In fact, I’ve always been told I tell stories different to everyone else. But there’s a good reason I feel like a number - I was literally a number in a previous job.

As I write this on the Elizabeth line train bound for Heathrow, two young professionals are talking about how much they earn working in finance. I’m listening to their conversation - they’re the only one in the whole carriage speaking and I’m nosey - and I’m bending myself towards their world. Their base salaries (they also earn commission) is about four times what I earn but they’re complaining about not getting a high enough expense account - it sounds like they’re pretty junior as they’re arguing with HR over getting £35 a day for food during a US trip.

Most of you would probably write off these twenty-something financiers as ghouls but I get drawn into their web and find myself questioning my life decisions. Or decision - the stubborn refusal to now ever undertake work which doesn’t fulfil me and/or help others. It’s this policy that has led me here and has seen me accrue a lifestyle far removed from these two wannabe high-flyers. They pursue money, I chase happiness - both aren’t a gradual linear climb.

I made this decision because in the past I tried to make a better living from journalism and work in an office for employers who paid well but placed no value in what I had to offer. If this sounds like a familiar situation to your life then I can only empathise but I’m not sure I have the solution.

In any case, I’m going to tell you about Number 6.

Disclaimer: details have been omitted because of a non-disclosure agreement.

The second best part of the day was the cycle to and from work. He would drop his two-year-old daughter off and then pedal with the baby seat attached giving him a constant reminder of the life he left behind - before he became Number 6.

The copy would be in the “queue”. And then he would edit it. Once he picked it up it would have his number - not a name - and the Orwellian scene would be complete whenever a writer would shout “whose Number 6?”.

They’d complain about some trivial change - English was often their third or fourth language - and then Number 6 would weigh up whether pushback was worth it. There was another office in India who edited the copy and Number 6’s manager once complained that the Numbers in London were paid too much compared to their Indian counterparts. The writers definitely preferred the Indian Numbers. Apart from when they made mistakes.

Number 6 drank a lot of water so that he could have more toilet breaks. The salespeople in this office earned 10 times what Number 6 did and they were prejudiced fools - he once overheard one of them in a lift say “Indians earned less because they were dirty”.

The manager of Number 6 was a chief editor but she never even logged on to the software even though she was the only one with a name not a number. The one thing she loved to do was handle complaints about the editorial output, which gave her power even though this was a simple task if she was in the office - a big if.

Her brother whom she would boast about was once was in the national news for being racist towards a man of Chinese origins. The siblings had lived in Hong Kong and had many servants - the transition to London was seamless as Numbers became her labourers. Number 6 would often fetch her dry cleaning, her lunch and answer her phone.

There was a ban on drinking alcohol at lunchtime. But this was the best part of the day when he went from being Number 6 to something else, something freer - a short but lovely transition. The Glad was a schlep but he only wanted one pint and when he was there he could be in a desi pub and see empowered British-Indians who called him by his real name.

Number 6 hated the walk back. Once he considered jumping off a bridge.

Hating a job is sometimes a fluctuating thing especially when a boss is changed. The helicopter that would swoop in and micro-manage the Numbers in London was upgraded to a B-52 bomber in New York who would drop explosives in situations that demanded attention. Number 6 became friends inside and outside work with B-52, not least because they supported Arsenal.

B-52 couldn’t change Number 6 to his name on the system but he came to the decision that instead of Number 6 that he would be Number 14, like Thierry Henry’s favoured shirt number. Number 14 now had a manager who empowered him.

Henry! But then the manager left and things got a lot worse. Number 14 was now managed from India. The arguments online got worse and accusations were made.

Number 14 was sent home one day. He wasn’t told why. Three weeks later, his number was up and he was offered some money to keep quiet - even though he didn’t know what he was accused of. Number 14 asked for details and a dossier was sent. Every conversation he had with the other Numbers where he spoke about the Helicopter was revealed even though every Number had complained about her too. Number 14 (and Number 6) had been sold out by his so-called friends.

But he wasn’t a Number any more especially because the pay-out offered him the chance of a new life. Number 14 became a writer and his name was everywhere.

What’s it like to be an author? I’m in shock. I thought about sending the Numbers the book - look what I’ve done! - but I feel sorry for them. They are the ones who have to live with their decisions. My life is full of hope, promise and kindness.

The press for the book has been overwhelming and the launch party (no tickets left, sadly) is on June 1 at the Glad (where else?). My intention is for everyone in the country to know what a desi pub is and for the word desi to enter the English dictionary. Which shows that even a Number can thrive.