The Black Boy pub, Tottenham - ‘It was disempowering and shaming’

How a black women's action group took on a brewery and won

If you like this story and want to support similar ones on this subject please donate here.

If you’ve not done so already please buy Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here - hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

I am a journalist who writes for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

Today’s article goes deep into issues that some might say fall under the umbrella of the “culture war” - note parenthesis, because I feel strongly that a lot of these subjects are either fabricated or wilfully misunderstood. It’s a phony war.

Take last year’s Gollywog scandal that surrounded a pub in Grays, Essex that flouted hate crime laws when a publican decided to display racist caricatures. In a public building.

Some people will say she’s not racist (yeah, right) but the point is putting up a sign on a door that said: “We’ve got gollies on display, if you find this offensive please don’t come in” is a colour bar with similar justification to many historic examples I’ve published. Too many to link.

I feel like someone like me might revisit the Grays pub in a few decades and detail how absolutely bizarre it was that people would defend the publican’s actions at the White Hart Inn and how it was turned into a binary defence of a certain type of Britishness.

But today I want to look at a subject that gained prominence in 2023, when Haringey council changed a Tottenham road name after consulting with the community in June 2020 amid the Black Lives Matter protests.

The road was called Black Boy Lane and it was changed to La Rose Lane, because some locals felt it was inappropriate due to the connections with slavery and racism. Others objected and felt it was virtue signalling especially because some similar place names are based on royal connections.

While a commonsensical view is provided by black feminist writer Stella Dadzie who told me that poet John La Rose wasn’t even from the local area (he lived in Finsbury Park), it was an expensive process and the signs still say “formerly Black Boy Lane”.

“I asked the woman heading this initiative,” Stella tells me, “if she knew the history of how it came to be called Black Boy Lane. If it was a negative or positive acknowledgement of black presence. And they had no idea - so they just changed the name simply because it has the term ‘black’ in it. Which is just bizarre - it’s a kind of whitewashing.”

This post isn’t about a street sign with a name that may or may not be offensive - it’s about the former Black Boy pub by La Rose Lane which at one time saw its pub's sign torn down after a successful campaign by residents, such as Stella.

Unlike the Black Boy Lane controversy this wasn’t a type of whitewashing.

Baroness Martha Osamor came to this country in 1963 from Nigeria when she was aged 24. Her initial experiences of life in England will chime with many children of the Empire who embarked on a similar journey in the mid-20th century.

“It felt like you were not wanted,” she tells me. “The signs said ‘no blacks, no Irish, no dogs’. No matter how much money you have you can’t get a place to live in but I didn’t think about it at the time, It was when I started having children and I thought ‘oh, my God.’

“We didn’t go into many pubs because of the [no blacks…] signs. If there was no sign it might not be safe unless you were in a group and then they might not want a group of you to come in.”

Martha came to this country to join her husband who was a student. They settled in Tottenham and in the early 60s she found the environment difficult to navigate.

“The hostility was out there,” she tells me. “[It was] everywhere. It felt like every institution was hostile unless someone said ‘it’s a good place, let’s go there’ It was the same as getting accommodation - it was by word of mouth.”

After a few years Martha and Stella became part of Tottenham’s community and by the late 1970s there was a focus on monthly meetings to fight issues that the black community faced, such as racist sus laws and school exclusions, under the guise of the United Black Women’s Action Group (UBWAG).

“It was an eclectic mix of black women,” Stella tells me. “Some of whom were at university, others were living, working and struggling in the community.”

Despite the name including ‘united black women’, these meetings were attended by white socialist allies including men. It was common for the organisers to seek help from local MPs, such as Norman Atkinson, or former Labour party leader Jeremy Corbyn.

They were needed because often an issue, such as black children being disproportionately excluded from schools, would be discussed on a night and then published by handing out leaflets. This was a frustrating process as often white residents would ignore the claims or believe they were lying.

“They would say: ‘You’ve got chips on your shoulders’.” Martha says. “To prove it we needed somebody like our MP. [Atkinson and Corbyn] were so useful to us. International Socialists helped us on the estate we lived on but the Labour party [itself] wasn’t helping us.”

Often black residents would bring examples of racism to the group, such as images in school books, and it was in this context that a complaint was presented about the pub sign at the nearby Black Boy pub on West Green Road.

A white Tottenham resident told me that the sign was present from at least the 1960s and embarrassingly admitted it was very offensive by the 1970s.

“I [thought that I] lived through this,” Martha says, “and now my children have to go through this as well - something has to be done.’

The pub was by a school and Martha and her comrades had children that would have to walk past that sign every day.

‘It’s not just our kids,” Martha says, “when [white people] see the sign it’s what they do to our kids and how they use it to traumatise them. But what do you expect the [black children] will think of themselves?”

Stella agrees that the sign should be viewed in the context of the school and the playground. “Schools then,” she tells me, “weren’t familiar with anti-racist policies and kids were still being called jungle bunnies. When [1977 TV series] Roots came out one of the worst insults to call a black kid was Kunta Kinte.

“This was more than an offensive image - it was recognising that when our kids walk through the school gates they are confronted with a barrage of both passive and aggressive racism.

“It was disempowering and shaming.”

The campaign had begun.

“Our aim was not to burn out ourselves,” Martha says, “it was to raise it. So that people are not encouraged to continue doing it.”

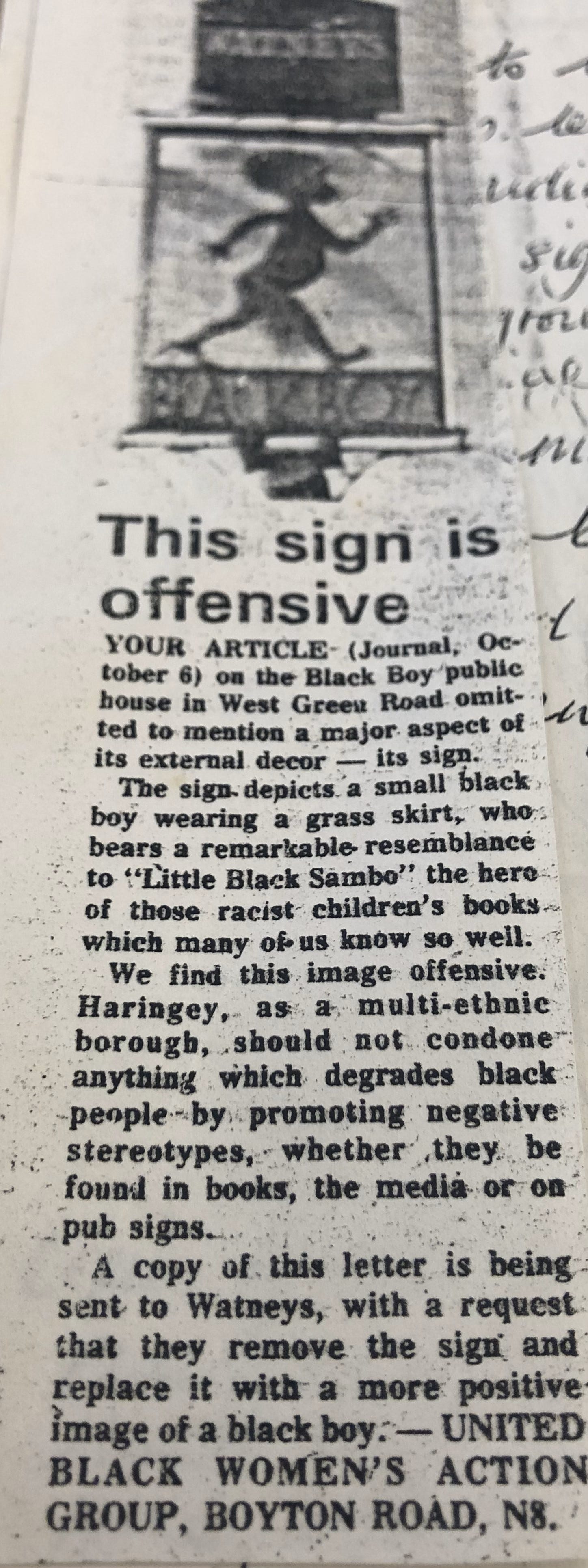

It started with a letter in 1978 to a newspaper after a puff piece was written about the area that mentioned the Black Boy pub. The UBWAG wrote a response pointing out the pub’s sign needed to be described as: “a Little Black Sambo, the hero of those racist children’s books”.

The letter, which was also sent to Watneys, the pub’s owner, requested the sign be taken down and replaced “with a more positive image of a black boy”.

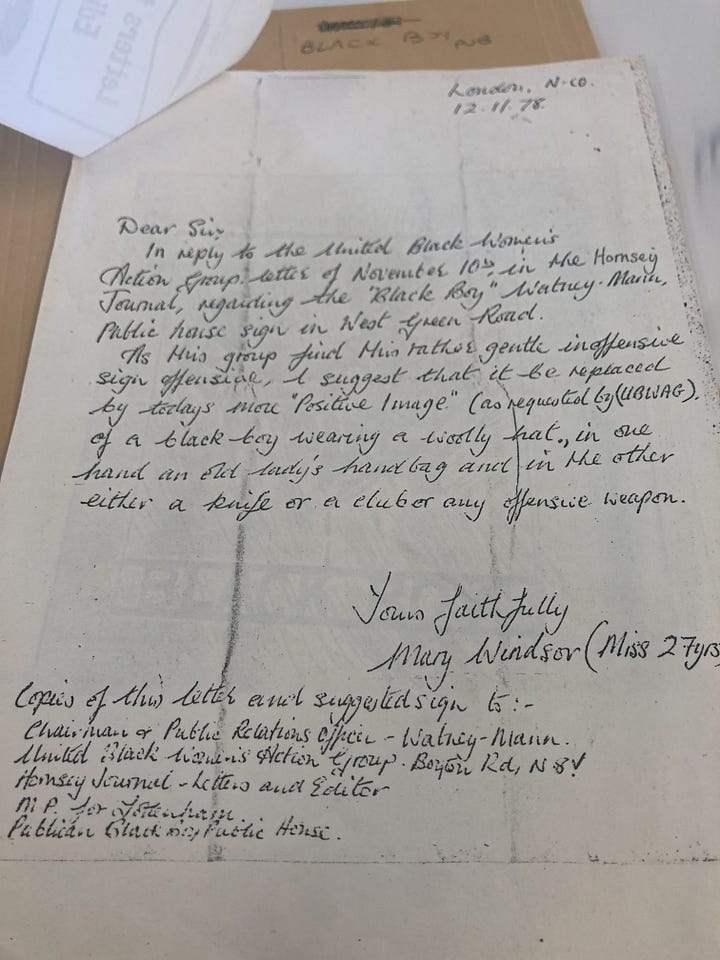

This put the issue in the public domain but like the Gollywogs in the Grays pub many leapt to the defence of the sign with one hideous letter - that was unbelievably printed - saying it should be replaced with a “black boy wearing a woolly hat, in one hand an old lady’s handbag and in the other a knife or club or any offensive weapon”.

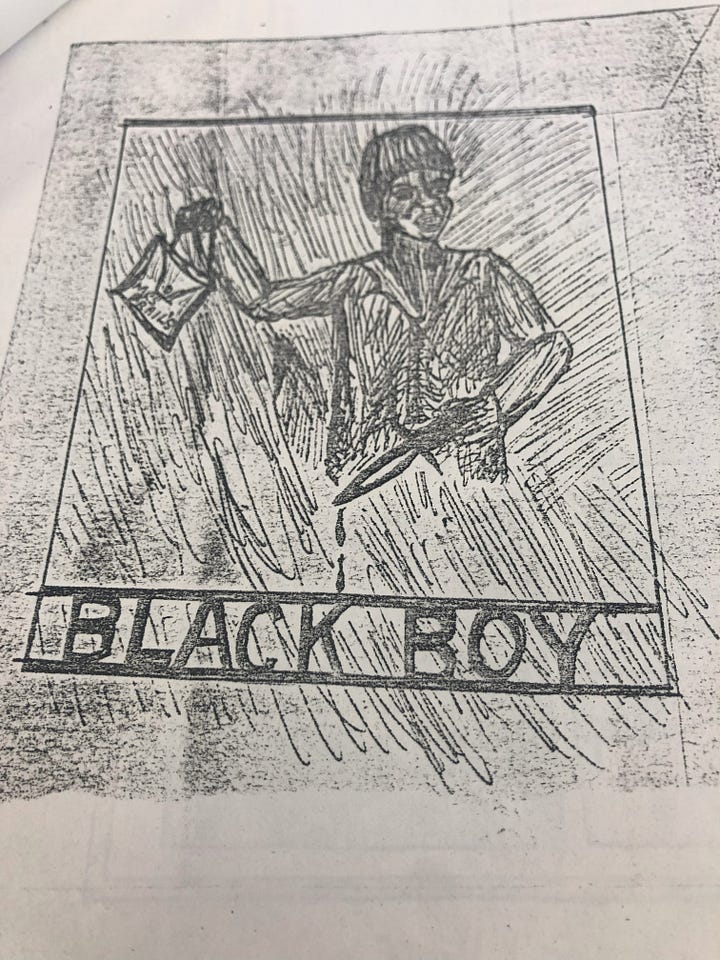

Just in case this wasn’t offensive enough, the same paper printed a scrawling depicting the mugger.

“The things they would write about us every week in the Hornsey Journal and the Tottenham Herald were unbelievable,” Martha says. “They block out the main thing that people like me were objecting to which was the sign and then promote the Black Boy name.”

The controversy, therefore, reminds me of the Gollywogs/colour bar in Grays, Essex.

“These tactics are used all of the time,” Martha says, “and people have short memories. And the idea of a group of people who feel so superior can sit down and say commission a designer to design an image of a black boy - the image of that grass skirt, caricature of a black person is drawn and put up. Can you imagine?”

The campaign was short and successful with Watneys (in the year it became defunct) removing the sign and replacing it with an image of a black horse. I put it to Stella that this was a rare victory from the left, mainly as I have so much personal experience of failure in such matters.

She disagreed that this was an isolated win because they had champions of causes, such as Bernie Grant, (deemed loony lefts) who worked with the black women’s group as Harringay council leader.

“We had quite a few victories in that period,” Stella says, “but in terms of taking on a group that was nothing to do with the council - a brewery - I think we were quite surprised how quickly they buckled.”

“The decision to take down the sign was a financial decision because they would have had black customers,” says Stella.

This week I visited Tottenham and the site of the Black Boy pub which is a shell, boarded up and simply sad. In its heyday it was a multi-roomed establishment with snooker tables and exterior adornments (mock wagons) that hinted at how carriages were washed nearby, according to one archivist I speak to at Bruce Castle museum.

She also remembers growing up when Tottenham was more rustic and she fed police horses with sugar lumps when she was a young girl, 60-odd years ago. But she’s not romanticising the past and remembers that it always was a diverse area with many Jamaicans established well before she was born.

In fact, I spoke to one man who came to this country in 1960 from the Caribbean island when he was aged 17 in the Elbow Room, a humble Craft Union pub, on Wednesday, about the Black Boy. The only thing he can really remember was drinking there and afterwards going to the club opposite, run by Irish people, that had a late licence.

There was no colour bar at the Black Boy, which was later renamed as the Black Grape before it closed in 2012. Just a pub with an archaic sign similar to these that formed an exhibition at the Turner contemporary in Margate.

“It was our community - we weren’t having it,” Stella concludes. “It proved to us that our voice was being heard. Those little victories were important because they were part of our civil rights struggle.”