The Midland Tavern - The joyful world of Cambridge's first black landlord

You would expect the life of Jamaican Albert Gordon to be marked by racism. Instead of colour bars, though, this is a story of inclusion, joy and reggae, reggae, reggae

If you like this story and want to support similar ones on this subject please donate here. As this week’s article shows, it’s the type of work that needs to be done to counter the hate out there.

If you’ve not done so already please buy Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here - hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”.

If you’re looking for information on BrewDog Waterloo this link will help.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

I am a journalist who writes for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

I love Cambridge. Many people ask me why I stay in Cambridge. I used to drive out in the country, especially in the springtime, listening to birds and smelling the fresh air. I’m a country boy and I love the country.

Today’s newsletter was magical to put together. It’s when an archival discovery has so much colour that I feel the characters come to life and we can take a timeout to visit a different world. Transport ourselves to a special place. All this is from one great interview, where our hero, publican Albert Gordon, spoke to Lucy Walker for the Mill Road History Project in 2016.

It gave me the same excitement when I was given the opportunity to listen to the tapes recorded by Avtar Singh Jouhl, but unlike that story this is one where hate doesn’t have to conquered. By now you’re probably used to me writing a lot about racism and when I was listening to Albert, who was labelled Cambridge’s first black landlord, I was expecting him to talk about prejudice at some point. I expected him to be like my dad - also called Albert and a one-time fellow Ford Capri owner - who came here only to be disappointed.

But that isn’t the story here. In fact, this is a tale that will bring a smile to your face and is an unchallenging joyful read - it’s not without its troubles but it’s the complete antithesis of this Cambridgeshire landlord who ruled his pub in the same era with hate and bile.

Albert Gordon grew up in Treasure Beach, southwest of St Elizabeth, Jamaica in the 1940s and 1950s - the third son of four boys brought up by a farmer father who raised cows, horses, goats and cultivated the land. But this was no utopia for Albert.

“Me and my old man,” he says, “weren’t living very well. We had some altercations and I didn’t want to stay there any more. I used to get beaten from him and he used to never care.”

Perhaps the reason was school. Albert’s father paid for his eldest son to be educated and expectations were high with the dad and boys listening eagerly on the radio to find out his exam results.

It was read out as a ‘fail’ and Albert’s father sat there in front of the radio in silence before cruelly pronouncing to Albert: “If you think I’m going to spend another penny educating you - it will never happen.”

“When I heard him say that my whole spirit sunk,” says Albert. “because I used to love school. One of my teachers was a farmer with a small holding - I used to take her things, corn, all sorts of things. I didn’t want to go home for lunch because my dad would stop us going back to school and find something for us to do.”

At times his dad would even take him out of school for months at a time because then it wasn’t compulsory. This led to Albert falling behind and when he was about 13 years old he took him out of school permanently. “I was so hurt by that.” he says. “I didn’t like him after that.”

The eldest brother - the one deemed a failure - had already left home to live with an aunt at Clarendon, south of the island. This left Albert lonely and yearning for education – he would spend all his money on a penny newspaper to practise reading to complement the history and botany books he would find around the house.

Even more spitefully, the second son was sent on a tailoring apprenticeship and Albert’s father proudly bought him a sewing machine when he completed the course. Albert, on the other hand, was sent at 16 years old to work with a second-rate carpenter because his father wouldn’t pay for a proper apprenticeship or any tools - “It was a waste of time.”

The psychological abuse continued with Albert being bought a bike by his dad only for him to take it away two weeks later. “He seems like he didn’t like me,” Albert says.

His mother even left him a goat which had kids, leading Albert to think he would become a farmer - like his dad - until “papa sold them”. Despite impressing white British adults with his knowledge of agriculture at a young age, his dad still discouraged education even when a British professor offered to pay for him to study at Harrow.

“I wanted him to show me love and affection,” reflects Albert, “but there was nothing there. I still love him though.”

Sometimes I used to just go by myself - a pub crawl. I used to love going out, drinking and I used to have a good time.

When he was 18 years old, Albert had his own chance to leave to avoid the beatings that his dad still would dole out over nothing - he even would thrash him with a stick in front of girlfriends. “I didn’t want to go to England in the first place,” he admits. “I wanted to stay in Jamaica. But I waited all day in a passport queue because I didn’t want to stay there with him.”

His three older brothers (one of whom was his half brother) were already in the UK. So he left his younger brother in Jamaica and flew British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) on 14 April 1960 via New York arriving the next day into Heathrow. Albert was completely flummoxed that it was still light after 6pm unlike in the Caribbean.

“It was such a strange experience,” he remembers, “especially coming from Jamaica. [I was a] country boy and not used to town life. It was such an experience. I thought everything was going to be like it is in Jamaica, like open space and you don’t have to lock your door or have a key to get into your house.

“I didn’t like it. I was scared to go outside in case I couldn’t get back in because living on a farm - you don’t have to use a key to get into your house. It was scary and I was a bit frightened.”

His mother was already in the UK, living in South East London in Peckham and Albert knew a few people from his district in Jamaica.

She had been in the UK from 1957, having left Albert’s father after he had multiple affairs with women and fathered other children - Albert’s father was a lot older than her, they were unmarried and she treated the man like a guardian calling him by his surname. In truth, Albert’s father may have acted like a country squire but she was the one supporting the family financially.

“There were a lot of us living in this house,” he said about 16 Highshore Road in Peckham. “At the time you couldn’t get a house from the English people - a Jamaican or, perhaps a Polish person, would rent you a room.”

His mother did the cooking and laundry, and his brother, Justin, who arrived the day before, was also in the house. “It was good to begin with but I didn’t have a job.”

He walked down Rye Lane and passed a TV shop - the first time he had ever seen a television set - and Princess Margaret’s wedding was being shown. “I was fascinated by it - I stood there for two hours.”

After a few weeks he got a job working in a laundry business (“a bag wash place”) which didn’t last long. At lunchtime he noticed his colleagues clocking out and then asked a clerk for his ‘cards’ - she interpreted it as he wanted to leave and he was dismissed.

“My previous work was on my father’s farm,” he says, “so I didn’t know nothing about clocking cards. I didn’t have another job for two weeks or so.”

He got another bag wash job for about six months paying £8-£9 a week, then he worked on the railways cleaning and oiling axle boxes at Rotherhithe Station, which allowed him to be trained to be an examiner (or ‘wheel tapper’) at Clapham Junction for £22 a week.

At the time his eldest brother was living in Cambridge and when he visited he discovered he was earning twice as much as him working for Cambridge Asphalt, which led to Albert moving to the East Anglican city. However, when his brother told him there was a vacancy at this firm he was lying because he just wanted him to relocate.

“I was living with him. Then I was on the dole for a while.”

He eventually got a part-time job at a small-works builder in 1963 before he finally did work at Cambridge Asphalt - “I used to earn £40 a week. Big money! Beer, liquor was cheap!”

In those days in Cambridge, a pint of bitter was less than 10p. “I used to just drink bottles but some English guy introduced me to pints. They say ‘you’re better off drinking pints’. He liked the Dog and Pheasant in Market Road (closed 1993), the Criterion, the King’s Arms, the White Swan and playing dominoes at the Durham Ox (now a takeaway on Mill Road).

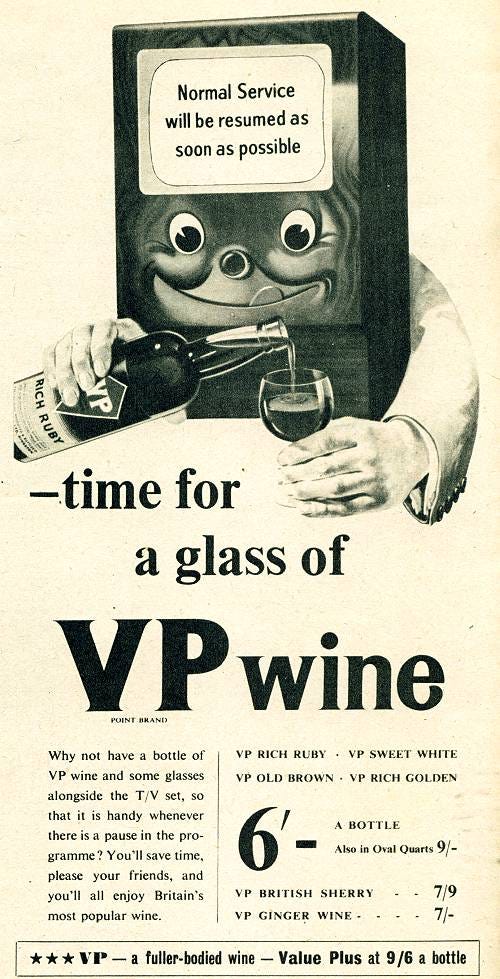

“At the time,” he says, “There were only a few black guys in Cambridge who had houses. We would have parties [at different houses] each week until four or five o'clock in the morning - a few cans of beer, a bottle of wine - mainly VP wine - sort-of a sherry.”

In Mill Road there was a landlord (“Mr Wallman”) who had VP wine on draft who would fill up Albert and his friends’ bottles for 10 shillings (50p). Sometimes he would give them credit if they didn’t have money - “he was such a good old boy.”

None of my children should go through the same sufferation that I had to go through from my dad

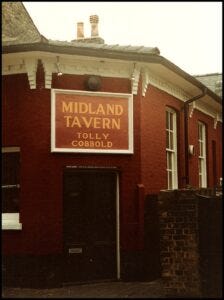

Albert met his future wife, Lorna, in the Midland Tavern (now the Devonshire Arms) on Devonshire Road where he would socialise and play dominos. Lorna ran the pub with her then-husband Michael.

Albert went in there one day after he split with his girlfriend when he was 28 years old (“I was a bit down and Lorna cheered me up”) and he told her that he liked her.

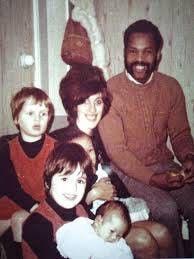

She said she felt the same and revealing to him she wasn’t getting on with Michael (Lorna and Michael were white).

“We made a date,” Albert says. “We started going out. It was the beginning of the affair and then she got pregnant. She told me it was mine and I said ‘how can it be mine when you’re married to Michael?’ She told Michael - and this is why I love the guy - he said ‘at least he’s a nice fellow’.”

Michael and Albert even became friends and they would watch horse racing together - when Michael first asked Albert upstairs, though, he thought “he’s going to do me in! I went but I was keeping my eyes on him, you know?”

Michael even explained and introduced him to the Grand National. “I picked this horse called Gay Trip [in 1970]. He said ‘no, that won’t win, it’s a little pony and the guy riding it is over 40’”.

Eventually, Michael called up his bookie, and put five shillings on Gay Trip to win and the horse romped in on odds of 9-1 but most amazingly was the reason Albert had picked it.

“I had a dream,” he says, “that I was at the seaside in a garden with flowers and everything. Everybody was so happy and they were eating dumplings and fried fish. And I thought … a trip, a happy trip a GAY TRIP - and that was the reason I picked that horse and it won.”

Michael wasn’t as generous towards Lorna and cut back on the money he gave her and their two daughters (Penelope and Lucy) for food, with Albert now also needing to be fed as his job at Cambridge Asphalt was weather dependent. The answer was trips to a cafe in Sawston where haggis was the cheapest item on the menu.

“For the whole week I lived on haggis and chips,” says Albert, “paid for by Lorna. I’ll never forget her kindness to me - that week changed everything for me.”

When the relationship became serious, Albert took on Penelope and Lucy and people would find it strange that two white girls would call Albert ‘dad’ but he used to laugh it off.

It was one of the places to go. It was the biggest cosmopolitan pub in Cambridge. There wasn’t many black people living here at the time and I know not of anyone who is black who has taken over a pub especially in this area

Albert owned a black and red 3L Ford Capri that was so fast that Lorna refused to drive it and it sounded like a jet engine causing him to be stopped by the police on numerous occasions.

“I had to get rid of it,” says Albert, “I was banned for six months. You only had to put your foot down and you’d be doing 30mph in first gear! Only a few thousand were made by Ford after that they were 2.8 litre.”

Lorna needed Albert to be responsible especially as she was planning to support an extended family. So she sold some shares, bought a three-bedroom house in Sawston for £3,500 with monthly mortgage payments of about £22.

A year later in 1972, Michael decided to give up the pub, so Lorna and Albert took a second mortgage out on their Sawston property and in an interview impressed the pub landlord, brewer Tolly Cobbold, who gave Albert the leasehold on the spot.

“We brought an atmosphere to the pub,” says Albert. “It became known as a friendly pub in Cambridge - you could come in there and chat with either me or Lorna. We had a good relationship with our customers. We help them, sometimes [they] ask us a favour - we would jump in a car and take them wherever they want to go.

“People loved us - even now people talk about ‘Albert from the Midland Tavern’. Everyone after tried to build on what we started. A lot of people came and saw how Jamaican people lived and the Jamaican way of life - the happy part of our life. One of the things we gave to them is the music.”

There was no food served but there was music. And, boy, was there music - reggae and soul - and every so often a steel band. There was also Northern Soul and once a month rock n roll with Teddy Boys (often associated with racism) turning up. “I tried to get everything for everybody in there,” Albert said.

It started with Albert paying a man a couple of quid to bring his soundsystem in, which led to a disco stage (it was the disco era) being installed and an application for a dancing licence - Albert wrote to the fire brigade, police and council.

The authorities point blank refused a dancing licence because it was a pub (dancing was for clubs) but Albert was undeterred - he hired a solicitor and was then only given a licence when they installed a fire alarm and fire doors.

Consequently in the early 1970s, the Midland Tavern was the first pub in the country with an official dancing licence. It became so packed it would take an hour to get revellers off the dancefloor with seven staff members pulling pints at once and customers having to fight their way to get to the bar.

“Because of the West Indian vibes,” Albert says. “They wanted to have music. On the Queen’s Jubilee we had a steel band and the whole of Devonshire Road was full of people.”

But to get here it was a bumpy ride with locals, police and councillors worried that Cambridge students were being corrupted by this music and dancing. Albert didn’t care because he was giving the people what they wanted - and apparently off-duty teachers and policemen loved visiting.

As well as music, there was a charity pram race where Albert got the locals to dress up as babies with dummies, bonnets and nappies. They would then be pushed in hired prams to other pubs where they would have to neck a half-pint of beer. The first ‘baby’ back to the pub would win a trophy.

“One man we disqualified,” remembers Albert, “because he missed a designated pub. He started crying so we gave him first prize.”

As well as sensitive locals such as the cry-baby, the clientele would be transient with Albert once hosting a Saudi prince who was a student at Cambridge university.

It was town and gown, with Irish people working on building sites or digging manholes loving pints of draft Guinness (or Guinness mixed with bitter) and they were so keen they would queue outside every day for the Midland’s 6pm opening.

“Those guys would spend so much money in two hours,” says Albert. “They would come in with their muddy boots and leave mud on the floor. I didn’t mind. The money they spent was good enough for me to clean up after them. Sometimes they would spend more in two hours than I would take in the rest of the evening.”

It sounds hedonistic, but Lorna made the pub child-friendly with parties in the beer garden, when she wasn’t upstairs with her own kids. At night, there were lock-ins, which Albert got in trouble with the police over when he was grassed up by someone who was milking a half of bitter all night.

Someone asked me if white people come here. Come down and experience it for yourself: it was a mixed culture. Anyone could walk in and feel comfortable

Albert was friends with a gay couple who ran the Kingston Arms and they would bring their customers to the Midland and vice versa. “We used to have a wicked time,” says Albert. “When people say straight people can’t interact with gay [people] it’s a load of rubbish.”

Lee, one of the publicans at the Kingston Arms, shared a birthday with Albert, and they celebrated with bourbon at the Midland (bought by customers who visited the US) and then went to the Arms to have champagne. “We were so drunk we could hardly move. It was a lovely time.”

Albert was always generous and if people were short of money he would give them pints, probably inspired by Mr Wallman and his pay-me-later VP Wine. But when it got busy they would have to make way for paying customers especially because Albert felt that the punters wouldn’t want to mix with waifs and strays.

Everyone, though, was included in the Midland. In the early 70s, Irish pubs were common and their clientele mirrored this but Albert described his pub as an “international pub” which was reflected in the staff with Italians, Swiss and Swedish nationalities represented, and in the customers. Saudis and Navvies.

It even changed Albert’s identity with him admitting he was more international than Caribbean - “We were people’s people. We were there for everyone.” But Jamaica was in his heart and the cultivation of its land - “I always wanted to go back.”

When the interview was conducted in 2016, Albert was bored and a little depressed at spending his days watching TV - the novelty of seeing a royal wedding at Rye Lane for the first time had worn off.

But Albert’s life offers an insight into a subject matter I’ve touched upon here and here about why black and/or Asian people - who may have been born in rural areas in the British Empire - didn’t move to the countryside in the UK.

“Coming to this country our main thing was to work,” he says, “and earn enough money to go back. We were told if you work here for five years we could earn enough money to go back to Jamaica and start our own little thing. But that was a big lie.”

When Albert left the pub in 1977, Englishman Derek Harvey took over the licence with his friend, Alan running the show. When Derek died, it was taken over by a Trinidadian called Winston Lewis then he was succeeded by a Jamaican, Trevor Jones - who worked under Albert - who again put reggae front row and centre. Jamaican Charlie Douglas took over from Trevor, continued the music, and then Tony Shaw and his wife held the licence.

When Tony left, the pub was put up for sale. Unfortunately, Julian (Albert’s son) failed to get the licence and was turned down by the new owners) maybe because he wasn’t married - which is a shame because Albert planned to make it a family pub, which served West Indian food.

Under auction it was sold to Milton brewery by Punch Taverns who run it today. And Albert left for Jamaica to tend to a bit of land left to him by his dad (who realised, finally, before his death that his hatred was misplaced) where he planned to grow organic food.

The legacy hasn’t been forgotten as the interviews with Albert (hear his voice here) and his step daughter show. The international nature of the Midland continues too with even a pub in Western Australia being named the Albert Gordon very recently.

What the story of Albert and his family shows is that sometimes there was joy in the most unlikely of places for people who called this country their home and forged inclusive spaces in pubs.