Tiger Bay, Cardiff - a lesson in diversity

How a rough and ready multiculturalism emerged out of a deprived working class area

This week has been difficult. Not only has it not been safe to visit certain areas, people like me have received a deluge of abuse from those emboldened by current events. So if you like this story and want to support similar ones on this subject please donate here. As this week’s article shows, it’s the type of work that needs to be done to counter the hate out there.

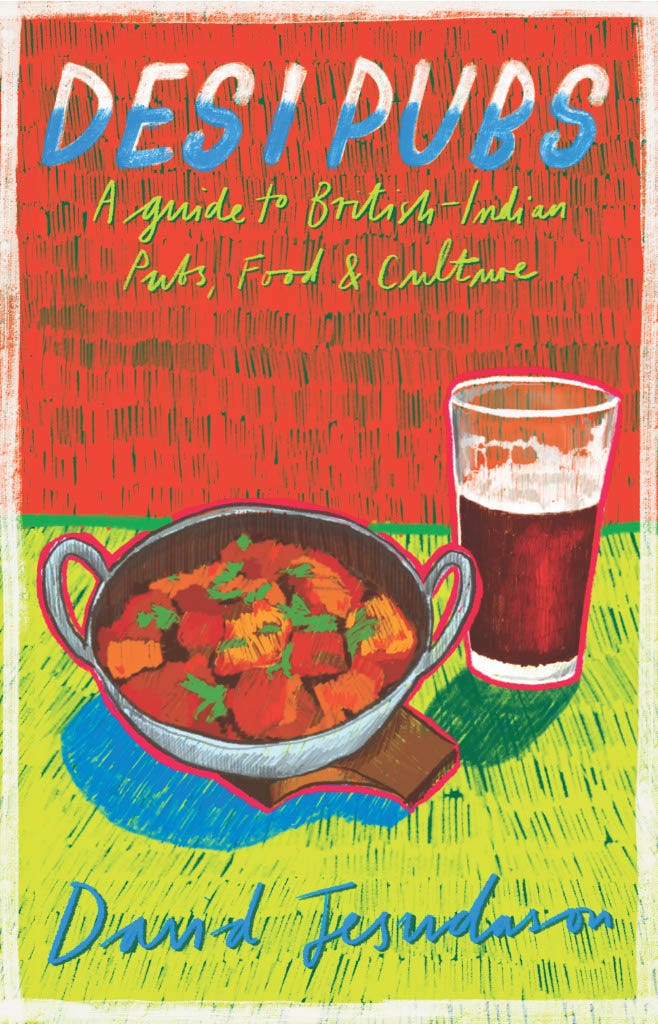

If you’ve not done so already please buy Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here - hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”.

If you’re looking for information on BrewDog Waterloo this link will help.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

I am a journalist who writes for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

Mosques attacked. Cars burned. People scared to leave their houses.

Current events are depressing but we need to react to them. If we don’t then the idea that far-right looters, rioters and criminals have ‘legitimate concerns’ will take hold despite this narrative first being peddled by shysters, such as Farage or Yaxley-Lennon.

To legitimise the ignorance of these far-right terror groups would be an insult to this country’s rich history or diversity - the extremists will have you believe that there was a Utopian time in British history that was economically charged by a grafting white population.

This will come as a shock to 17th century weavers in India who found their livelihoods bloodily stolen by the East India Company, who used weapons to drain the wealth from Asia. It will be a surprise to the men from the Punjab who fought against racist segregation to fire the British car industry. It would probably even startle my mother who worked her whole life for the NHS.

But they don’t care about history or even personal experiences of racism because they’re inconvenient to their false narratives.

Their violent acts are also an insult to this country’s history of inclusion. Often I don’t write about this facet of the past because it’s tricky to find sources - “Black Man Allowed In Pub” isn’t a headline that’s ever been printed.

But today Kieran Connell, senior lecturer in Contemporary British History, at Queen’s University Belfast, who is about to publish a new book Multicultural Britain, speaks to me about historical diversity in the UK.

The one great example of how migration into this country wasn’t a new experience and had inclusive elements is in his first chapter which focuses on 1940s Cardiff and this is what I will be mainly discussing today - the story of Tiger Bay.

Before I start though, you might wonder why Kieran - and I - focus on the past so much if we now have a multicultural country but current events show we have to. In fact, Kieran believes it’s vital for us to do so.

“Because the debate has been hijacked by the far right,” he told me on the day of the recent General Election, “And the Overton window has been dragged all the way to the right by successive generations of the far right despite [until 2025] them not winning a seat in Westminster [Kieran says Oswald Mosley wasn’t far right until after he was an MP] - I would argue they’ve still been successful in dominating the debate around race and immigration.

“What I can do as an academic - and what you can do as a journalist - is drag that back and force people to reckon with what is the fundamental nature of multicultural Britain.

“It’s just the reality - and it’s not just the reality of London, as my book shows, or even big cities of Birmingham, Nottingham and Cardiff - it’s actually affecting small towns. Milton Keynes, to give you one example, is now far more diverse than Birmingham was even in the 1980s.”

Kieran’s book, which is published mid-September but available on Amazon, doesn’t celebrate multiculturalism without highlighting racism - the two often go hand in hand - but shows time and time again that multiculturalism exists through the toil of white and non-white working class people.

His book is filled with stories, such as the white sex workers in Bradford who saw their brown boyfriends (and pimps) be subject to colour bars and of British people seeing their lives changed by an influx from other countries.

To be honest he’s not like other academics I’ve interviewed, growing up in a traditional working class mining town in the East Midlands informs his worldview and makes him - aside from his sources - an embedded vital voice.

After all, there’s a reason he was one of the first experts to be quoted in my book when he said about white people who stayed to see their areas enriched by desi pubs: “In a rough and ready way they’re the vanguard of multiculturalism.”

Today is a celebration of those who are the vanguard of multiculturalism.

Cardiff’s Tiger Bay in 1947, according to African-American sociologist and anthropologist St Clair Drake’s archives, was a cosmopolitan rival to London’s East End. He spent a lot of time immersing himself in the bay’s culture and keeping a diary of his experiences when meeting the diverse inhabitants.

Ebony Cafe, Cairo Lodging House, Singapore Cafe, Satar’s Arab Lodging House: St Clair was agog with the vast array of different cultures and how they appeared to mix merrily with Welsh people in parks, on the streets and at sports clubs. This was a different vision to the American South.

During the second world war, the US army - with its legions of African-Americans - was stationed in bases near to Tiger Bay. This meant that in 1947 not many people cared that a black guy, nicknamed the professor, was being a flâneur, in a time when Jim Crow violently opposed the mixing of races in St Clair’s homeland.

The African-American soldiers formed relationships with the local women and this led to mixed-race children being seen running happily through the Tiger Bay streets. That’s not to say there weren’t moral panics about “inter-ethnic” relations during the war but, in general, authorities wanted to portray a facile permissiveness to counter Nazi ideology.

Post-war life was difficult though for mixed-race children, such as Roger Burnham, who was born in the early 1900s to a black seaman and a mixed-ethnicity woman from Southampton. When he left the Bay he would be shouted at: “look at the black man” or “look at the nigger”.

Newspapers decried mixed-raced people like Burnham as “Britain's half-caste problem” and they were seen as at the bottom of the non-white hierarchy.

As well as the large mixed-race population, in 1947 Tiger Bay, there were more than 2,000 Muslims including a 700-strong Yemeni Sufi community, which led to many cafes-cum-bars being opened, which are vividly described by Kieran.

These were large, semi-clean rooms with a strong smell of food in the air. “A counter selling groceries alongside hot food, cups of tea, lemonade, and anything from Australian wine, meths and ‘near beer’ to diluted whiskey sold at seven shillings a cup.” They could legally sell alcohol until 11pm - one hour later than the pubs in the area.

An aerial bombing of Peel Street mosque, in 1941, meant that establishments like Cafe Cairo would be multi-functionary, doubling as temporary places of worship and gambling dens. Craps, a dice game popular among African-Americans and Caribbeans, caused lookouts to be stationed watching for police with sums as large as £20 gambled.

But the cafe culture in the Bay, according to Kieran, was most strongly associated with sex work and Maltese cafe owners/pimps. They officially employed white women as waitresses who in reality spent their days sleeping with ethnic-minority seamen; these punters in turn risked being robbed, cheated or beaten up in bar fights, when paying for sex.

Tiger Bay, Kieran argues, was like red light districts in Balsall Heath, Birmingham and Bradford in that it gave white women their first insights into racialised people.

“The key point of the Cardiff chapter,” Kieran tells me, “is you see this really rough and ready multiculturalism emerge out of these very deprived working class areas.”

Kieran tells me that the white people in Cardiff during this time understood race on a sliding scale when coming into contact with Yemenis, Somalians or West Indians, because of the British empire - race itself being an empirical construct.

“Most historians up till recently,” he tells me, “understood the empire as something that happened overseas. And [their view] was it didn’t impact the mother country very much. In more recent times historians have shown that this is completely wrong and the empire was a really big feature in everyday life in Britain as well.”

He then goes on to argue that the rapid decolonisation of the British empire - starting with Indian independence in 1947 - caused significant trauma.

“This trauma,” he says, “is being processed - or not being processed - at the very same time you have these living, breathing signifiers of Britain's colonial past not even just moving in next door, not only drinking in the same pubs, not only applying for the same jobs but getting into relationships with local white women.

“This causes some of the biggest psychological trauma, not just among politicians like Enoch Powell, but teddy boys and skinheads.”

I’d argue that this amnesia about the past is still causing trauma and opportunities to divide today. History - despite a lack of knowledge of it - keeps repeating itself.

The Coloured International Athletics Club (CIAC or ‘Kayaks’ to regulars) was a place where ethnically diverse residents come together to play sports, primarily rugby, and to socialise afterwards with drinks. But delving deeper shows it was a lot more than a simple sports club in Cardiff.

“Some people,” Kieran says, “wanted to turn it into a formal pan-African, anti-colonial, political organisation. It was more of a space of sociability - of chewing the fat, shooting the shit. But that in itself is political. In the late 1940s, there was a younger generation of mixed-race men who were trying to turn it into a ‘respectable enterprise’.

“That again was political because it was pushing back against the discrimination that affected mixed-race people when there was focus on the sanctity of the ‘white race’.”

Ordinarily ‘half-caste’ (this is an offensive term I know too well, being ethnically half Indian, half Malay) people were expected to be at the bottom of a hierarchy but this was upended at the CIAC.

In fact, the younger members of the CIAC identified with Bill Douglas, who was born in Britain in 1917 to a West Indian father and white mother, and became one of the earliest black players at Cardiff Rugby Club.

In 1948, the CIAC organised a black-tie event to celebrate Douglas’s success after he made 39 first-team appearances for the team, with the CIAC inviting white members of Cardiff Rugby Club.

Announcements were placed in Tiger Bay shop windows and St Clair attended the night which was held ‘not at a dingy clubhouse’ but in the convention room of a city-centre hotel rented for the occasion.

“He [St Clair] entered the hotel,” writes Kieran, “without any of the stares or comments that might ordinarily greet someone from an ethnic minority in central Cardiff. In the hotel lobby, he spotted five white girls and two black girls chatting with a group of four white boys.

“Further on, four or five boys of mixed ethnicity were trying to set up a large keg of beer.”

One of the attendees was CIAC stalwart Alan Sheppard, a Guyanese former seaman and illegal bookmaker, who once said: “Gambling has always been thought of in this country as a gentleman’s game but they haven’t wanted the bloody poor man to do it.”

Prior to the guests arriving at the event, socialist Sheppard was dressed in a newly pressed suit - sans his weather-worn hat - and was told he had to toast the king. Drake overheard him being shushed when he said “I have never toasted any bloody king and I don’t intend to now”.

After the dinner was served by an all-white waiting staff, Sheppard gave a speech but read the room and in the end did toast the king. This lead to knowing grins among the Kayak boys - but it was Bill Douglas himself who fittingly summed up the occasion by saying: “It’s good to see a Cardiff team with both black and white faces. I’m proud to represent Tiger Bay where I was born.”

“The guests then danced,” writes Kieran, “with no evidence of colour-bar induced awkwardness.. There is something important about a group of young mixed-race people rejecting the hostility directed at them in 1940s Britain, and in defiance, trying to articulate a sense of pride in their own formations.”

It’s a lesson for those who need to be taught that British history is interlinked with empire, diversity and overcoming racism. The history of Tiger Bay is a series of events that are an inconvenient truth for the demagogues who seek to sow hate.

They would rather it remained hidden.

Multicultural Britain - A People’s History by Kieran Connell is available on Amazon

Recently I wrote about McColl’s brewery and men’s mental health for Pellicle, mixing Guinness for VinePair and appeared on BBC Sunday Morning Live talking about desi pubs