Island of friends: re-discovering Alex Samos

From Samoa to Britain via New Zealand, almost everywhere Alex visited he was loved. He lived a life of joy and optimism despite the racism he encountered

These articles are vital and entirely funded by me, so please donate here to continue to support similar investigations. If that link doesn’t work for you (or if you’re paying by Mastercard) then you can also use my Ko-Fi here.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse. Today’s newsletter features accounts of racism and exclusion.

Please follow me - Desi Food Guide - on Instagram here. I’ll explain why next week.

I’m a sucker for a happy ending especially as they’re rare in the days when a Labour PM deploys far-right rhetoric in his now infamous ‘island of strangers’ speech. Which makes this newsletter extra special.

When I wrote this article about Alex Samos, who was barred from performing at the Willesden Legionaire Club in 1984 on grounds of colour, I didn’t expect him to be alive.

Not only is he fit and well, but he was more than happy to share how he flourished despite racism. His daughter, Hannah, loved the article and passed it to Alex who gladly filled in all the gaps about how one racist incident was just a blip in a joyful life.

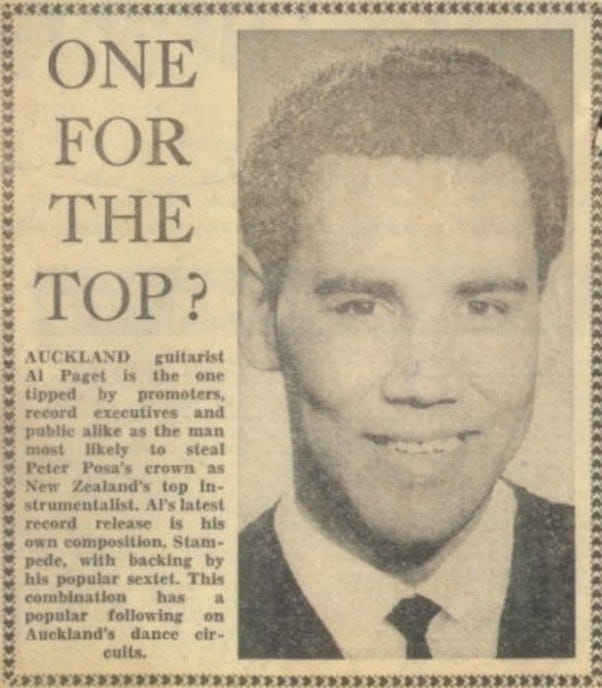

So here’s the wonderful world of Alex Patchett (stage names Alex Paget and Alex Samos).

In 1937, Alex Paget was born in Samoa and growing up he and his friends would regular skip school to play on the beach and in jungles. He was a mixed-race child with parents that were both half-Samoan, half-European, reflecting the multicultural make-up of the Polynesian paradise.

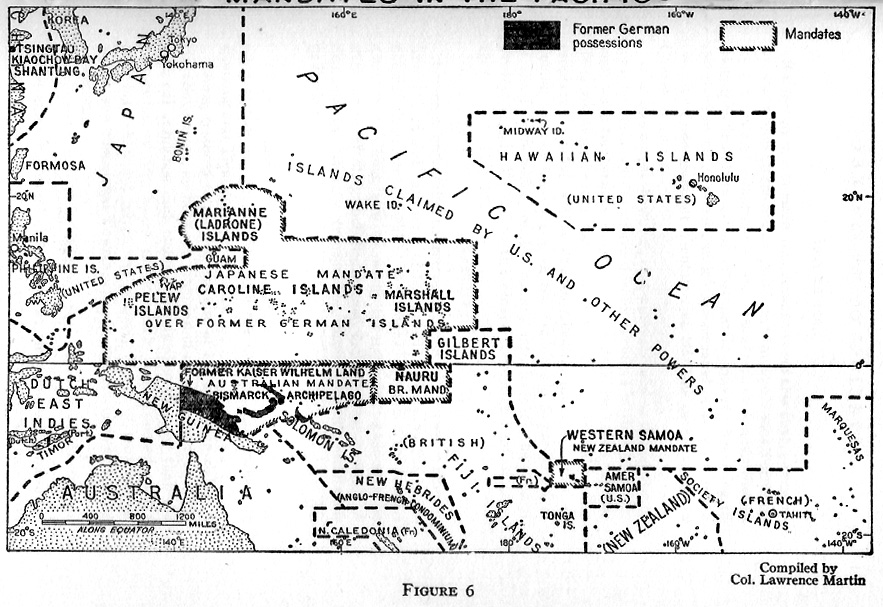

During this time, the Samoan islands were mandated to New Zealand by the League of Nations as the Pacific was divided up between France, the US and other colonial powers.

When he was aged 12 his parents divorced, his mother met a Kiwi and they moved Alex and his siblings to New Zealand. Going to the beach instead of school stopped.

“Seeing apple trees and [the climate] being cold stuck in my mind,” Alex tells me.

But Alex admits it wasn’t too much of a culture shock although he remembers an unsuccessful campaign to set up a white school - institutions in those days were divided by ‘mixed’: whites and indigenous and ‘half castes’: those soley of mixed race.

Skipping school stopped but music soon took over. His brother brought home a guitar when Alex was aged 18 and he fell hard for the life of a musician spending all his time practising or going to see bands in the era of Bill Haley and the Comets.

A year later he himself was in a band during the time Elvis Presley scored his first hit with Heartbreak Hotel. They played Hawaiian music and became the most popular act in Auckland drawing huge crowds at the city’s dancehall where they had a twice-a-week slot.

Alex wanted a new challenge and formed his own band called the Al Paget Sextet. At first the band played a mixture of styles - rock n’ roll, standards, jazz, Latin etc - but when the Shadows became popular they pivoted to two guitars, bass and drums.

In 1967, Alex arrived in London as a solo act - he had disbanded the Sextet but one former band-mate had travelled with him so there was no animosity. The plan was for Alex to work as a primary school teacher in the day and gig at night.

Apart from being taken aback by terrace housing as people lived in bungalows in New Zealand, there was no culture shock and Alex was happy to hang out at Denmark Street with other musicians.

He soon realised that the good money was in cabaret as he could earn the same pay as a night’s performance for a half-hour set (and then perform his cabaret act again at another club). Alex, for example, would play an early gig in Bournemouth and then get back to play a lateshow (1am) in Soho.

The type of music he performed was Latin American with Sambas and “cha-chas”.

During this time Alex would be booked by agents who represented other acts, such as Mike Reid, and he shared bills with the likes of Lenny Henry.

This continued into the 1980s, with live performance being the gold standard until karaoke came along, with pub and club bosses working out they didn’t need to pay acts if their own customers were willing to perform.

Alex also believes the timing was unfortunate because it coincided with the rise of Thatcherism which led to a lot of clubs shutting in the north as her policies started to decimate industrial areas.

“It was the beginning of the end of entertainment in clubs,” Alex says.

Alex also started to suspect that black acts had a rough deal with many telling him they didn’t get booked as much. He later discovered that it was a common practice for clubs to ring bookers and demand only white acts.

“They weren’t all like that but some were,” he admits.

Alex was booked to play the Legionaire in December 1984 for a £60 fee. This was the third time he had played the club and he was prepared for hostility because the club entertainment manager had tried to bar him on his last visit.

During that second booking he had said to Alex: “You can’t go on because you’re coloured.” After a major row, Alex had eventually been allowed to perform but Hines - the man who had used the racial slur when talking to Brian - rang one of Alex’s representatives to complain.

Cindy Denham, Quality Acts, remembered that Hines threatened her by saying “I was to remember the policy of no coloured acts.” Now the club wanted Alex to leave the premises when he arrived and his agent George Fisher was told Alex needed to be replaced because of his colour. This time the club “won” and Alex was barred for not being white.

Willesden Legionaire Club - ‘You can’t go on because you’re coloured’

The details of the incident at the Willesden Legionaire Club - as I reported were confirmed by Alex but a crucial detail was overlooked: the vital role of agent Cindy Denham.

“It was a really unpleasant experience but I wouldn’t have succeeded without Cindy,” Alex says, “because I needed someone to back me up. It was courageous what she did because she could have lost a lot of work.”

Cindy booked acts for a lot of working men’s clubs and would’ve seen a lot of prejudice first-hand by being a woman - Alex has lost contact with her, though, but believes she was the only non-male in this role. By giving evidence to the tribunal she acted as a white ally and the duo were also backed up by Equity.

It perhaps was an easy win because, apparently, when the Legionaire Club submitted evidence for its defence it gave details of an “inclusive” boxing club - but instead of saying black boxers they used the N-word under oath.

“It was a step to stopping all the nonsense in the clubs,” Alex tells me. “I just couldn’t let them get away with it and I hoped it would’ve helped other people too.

The aftermath is also a revelation. When Alex performed at a nearby club soon after the case he wasn’t afforded a hero’s reception - quite the opposite.

“I went on stage and a large section of the crowd booed,” he says, “I walked off. Word got around and I was the recipient of their anger - how do you challenge that?”

Worst still, Alex believes clubs were less dangerous than pubs at the time because at least they had a form of sanctioning of anti-social behaviour. He retells numerous times that people shouted abuse at him, calling him racist names, in pubs.

Alex went back to teaching, occasionally gigging at night - living in Gants Hill in Redbridge, London. Now he’s retired. But live music still played an important part in his life and he performed at care homes until Covid struck.

He has three children and two of his daughters studied at Cambridge. Hannah Patchett had this to say: “It’s hard to imagine the small minds of people who refused to be entertained by a black musician, even as late as the 1980s.

“What my dad did was important because he stood up to racist treatment and he exposed a colour bar. It was an act of resistance. My dad’s an optimistic person and I think pursuing this case showed hope and imagination that we could be better.

“It feels sad, though, that 40 years later, small-minded people (and politicians) still feel entitled to decide who belongs and who can be pushed out.”

I am a journalist who writes for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

I’m offering my book, Desi Pubs, at Amazon prices. I can have it sent to you very quickly for £12.29! Message me on Bluesky for copies. There’s a review of it here.