Willesden Legionaire Club - ‘You can’t go on because you’re coloured’

It's 1984 and a working men's club is taken to court for its colour bar

If you like this story and want to support similar ones on this subject please donate here.

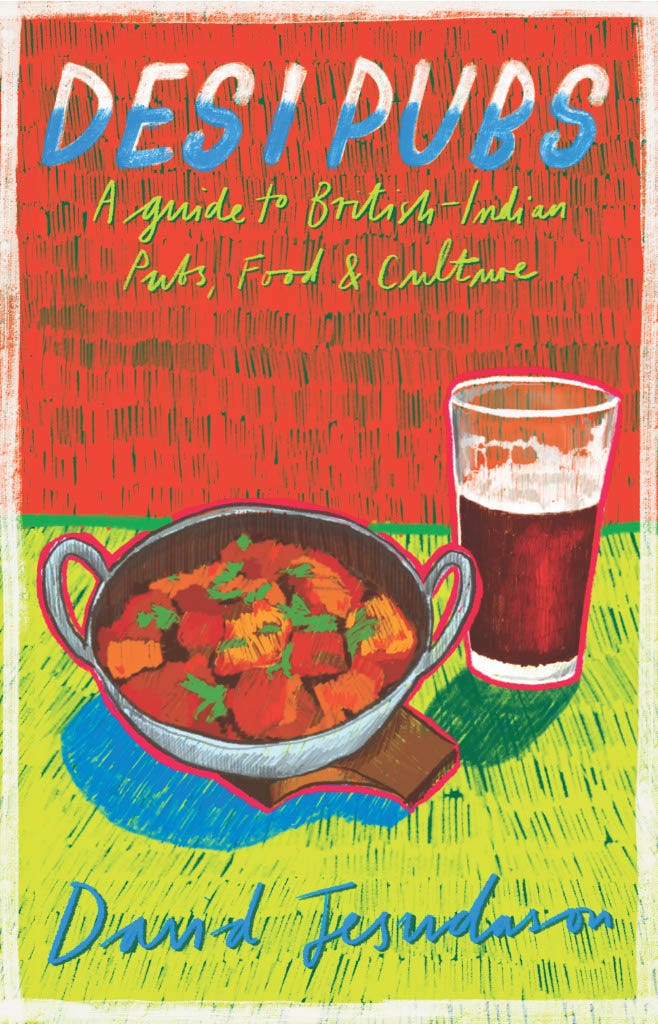

If you’ve not done so already please buy Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here - hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”.

If you’re looking for information on BrewDog Waterloo this link will help.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

I am a journalist who writes for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

Finding unarguable examples of the colour bar from the 1980s onwards is very difficult unless I do a lot of footwork like I did here - and even then this example of segregation was operating under my nose at my local pub.

But there were a few successful modern law cases that took hospitality operators to court for discrimination on grounds of race and won. Today’s example centres around a musician who took on a racist-run club which barred him for being non-white and then admitted they only had white members, like the Handsworth Horticultural Institute.

The information here was mainly drawn from newspaper archives but there’s also a valuable interview from a friend Brian Damage who performed in the 1980s at clubs and pubs as a music act - I knew him when he was one half of a comedy double act and ran a comedy night in Fitzrovia.

I also would like to thank New Zealand beer writer Mike Donaldson for his help - it really was an international effort this week!

This might be a story of racism but it’s also a trip back in time to an era when people visited clubs and pubs a lot. When entertainers could earn a decent living if they were willing to put up with a few, well, hardships.

“London had thousands of pubs,” says Brian Damage, “and you could work every night of the week if the pub had the money.”

In the days before big screen TVs, the internet and more than four channels, it was possible to earn a decent living as a music act playing pubs and clubs in your local area - especially if you lived in London and owned a car.

Brian was one of these acts on the cabaret and music circuit. His Irish parents were pub musicians and he followed them into the trade when he was in his 30s after buying a pub directory around 1983.

He would ring the pub directly and speak to the landlord to see if they had music, keeping a foolscap (330 × 200mm) folder of the results. Brian found that he would be booked by one in 20 pubs he called, which shows that he was persistent but also the amount of live music that was booked at the time.

His act was music with “old” jokes in between “tried and tested by other comedians” - it’s only when he discovered the alternative comedy scene in the Greyhound, in Sydenham, South-East London, a few years later did he seriously sit down and write his own material.

“If you wanted to play [music] somewhere nice the money was rubbish,” Brian admits, “But if you wanted good money you were singing to drunks, idiots, the local arsehole pub. The clubs were a bit more upmarket.”

Despite this Brian preferred singing in pubs because there was only one person to impress - the publican - “if they’re behind the bar and happy it doesn’t matter if the punters aren’t happy”.

Often he would be booked in pubs if a new publican wanted to get rid of some locals and he would regularly perform to an audience who’ve turned his back to him.

The reason why he put up with this humiliation in pubs was clubs, such as the Legionaire in Willesden, north-west London, had about 10 entertainment committee members and any one of them could approach him and offer him feedback, such as “can you liven it up a bit?”

Brian tells me comedian Roy Chubby Brown wasn’t a committee fan as well and used to say “I did a gig for the TUC club. Named after the committee - ten useless cunts.” They also had an older demographic in the audience and Brian says they made you feel unwelcome for just being younger.

Pete Brown, beer writer and author of the book Clubland - How The Working Men’s Club Shaped Britain, said those on the entertainment committee (and the entertainment chairman) were members of the club first and foremost with a few using the role to gain experience to become an actual promoter.

“Others took the job for a power trip,” he tells me, “it was the highest status role apart from the [club] chairman. If you were booked by a club you did it on their terms - it didn’t matter who you were.”

Brian one day in the mid-1980s was booked by the Legionaire. He walked in before his set and met the entertainment manager, Lou Hines, who greeted him by saying: “Look around, do you notice anything? No niggers! Out in the street, yeah, but not in here.”

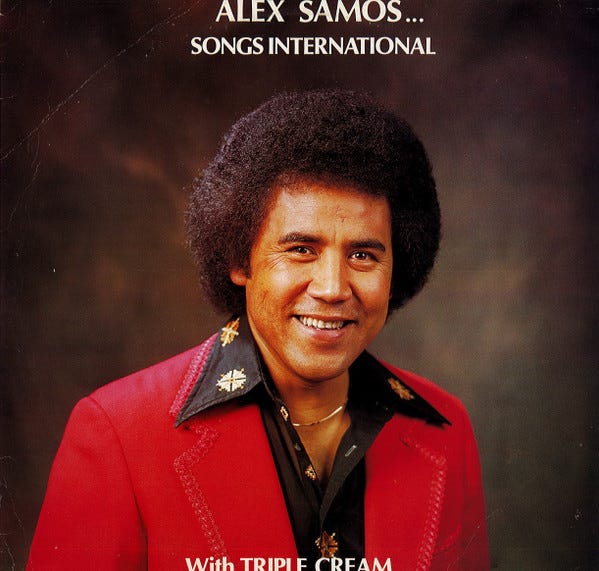

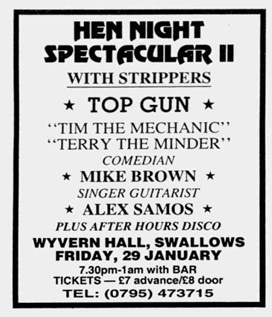

Alex Samos was a New Zealander of Polynesian parentage, a teacher who came to Britain in 1967 around the age of 29. He became a musical act shortly after he arrived after undertaking singing lessons with a British tutor.

He was registered with an agent from at least 1976 where he would regularly play Chaplin’s in Swallow Street, Mayfair and was once billed as a future TV star.

According to one of his backing singers, Dave Brock, 65, Alex was a gentle, family-man type of person who appeared a lot younger than 47 in 1985.

Alex’s music was described by Dave as covers of Latin American tracks and was percussion-based - Dave would hand out instruments to audience members and give them “something to rattle”. The music, he says, was the cha-cha-cha, that type of thing.

It was common for acts then to be on the books of numerous agents, with Brian saying they wouldn’t give you much work, usually calling at short notice if someone cancelled. One of Alex’s representatives confirmed to me he would play gigs with the likes of Jim Bowen and working men’s clubs, even a gig in a nuclear power station site.

Dave reckoned Alex could earn up to about £150 (£450 in today’s money) a night and would also have a sideline in selling his own records, which were still cheap to press in the mid-1980s even for a small run of 100.

When Alex appeared on mixed bills - the Legionaire was a single act night, though - he would close a first half or open a second half. He was a light entertainer, like Brian, and not a headline act.

Brian would see Alex’s name on posters but as he rarely performed on mixed bills he never met him. Alex, like a lot of his contemporaries, was an act until at least 1993 - when entertainment moved into the house courtesy of Mega Drives and Sky.

“Most of us never met each other,” says Brian, “but you would get to know who played in a certain pub. Word went round he was discriminated against. Clubs were normally safer than pubs but they were just as capable of pissing you off.”

Alex was booked to play the Legionaire in December 1984 for a £60 fee. This was the third time he had played the club and he was prepared for hostility because the club entertainment manager had tried to bar him on his last visit.

During that second booking he had said to Alex: “You can’t go on because you’re coloured.” After a major row, Alex had eventually been allowed to perform but Hines - the man who had used the racial slur when talking to Brian - rang one of Alex’s representatives to complain.

Cindy Denham, Quality Acts, remembered that Hines threatened her by saying “I was to remember the policy of no coloured acts”.

Now the club wanted Alex to leave the premises when he arrived and his agent George Fisher was told Alex needed to be replaced because of his colour. This time the club “won” and Alex was barred for not being white.

He took legal action against the club and, in a case backed by the Commission for Racial Equality and Equity, won £500 (£1,500 in 2024) compensation for injured feelings and loss of earnings in August 1985.

“I hope this would stamp out discrimination by clubs against coloured performers,” Alex told the press at the time. “I thought it was an affront to my dignity. I was outraged.”

Club secretary Michael Riordan confirmed none of the 500 members were non-white but feebly retorted that “no coloured people had applied to join”.

He then tried to deny there was a colour bar because Samos had performed three times before and the excuse was committee members said he’d played too much at the club.

“If a club cannot change its mind,” said Riordan. “I don’t know why we are running clubs. A white entertainer would’ve got the same treatment.”

The club president conceded, however, that Hines would not be standing for re-election the following year and if they had known of a colour bar “we would’ve squashed it immediately”.

Whatever the excuses, this was the first successful legal action against a colour bar for entertainers and it highlighted the obvious racism of the club. It even gained international coverage with the story reaching Alex’s place of birth, New Zealand.

At the tribunal, even chair Stella Hollis said she was surprised by revelations that discrimination on the grounds of race was widespread within the entertainment industry.

Alex concluded: “This has achieved what I set out to do: expose this nonsense.”