Handsworth Horticultural Institute - 'I bought a house and the neighbours moved'

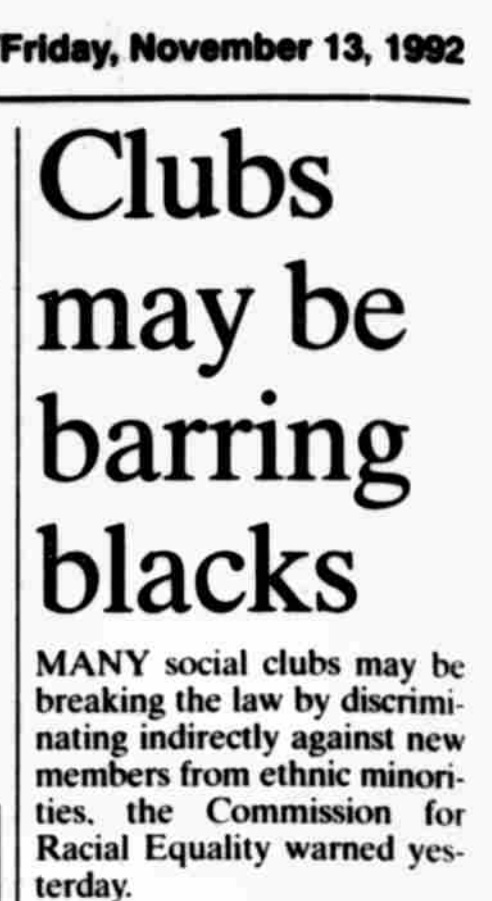

A working men's club in Birmingham was investigated for operating a colour bar in the early 1990s. They weren't an isolated case

This article originally stated that the venue was called Handsworth Horticultural Institution. This has since been amended to Handsworth Horticultural Institute.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse. It can also feature descriptions of racism and segregation.

A lot of people have signed up to the free weekly email recently and there’s a question of how to support the work I put into these posts financially. I publish them to promote the book so please pre-order Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here and/or donate £3 here.

When I was researching the life of anti-racist campaigner Avtar Jouhl Singh (whose stained glass window in the Red Lion in West Brom I wrote about last week) I realised that there was widespread ignorance on the subject of segregation in pubs. University-educated friends thought it was a US or South African event, despite Avtar famously introducing US civil rights leader Malcolm X to a racist pub in the 1960s.

It got to the point where I had to scour old newspapers detailing hate crimes to create a Wikipedia page because a general page on segregation said it didn’t exist in the UK. I also found that all these accounts were from the racists’ perspective with victims (or campaigners, like Avtar) rarely being interviewed. Although it’s embarrassing to say that journalism is 92% white today, in the past it was even less diverse which explains why more weight was put on white people’s accounts.

After having written extensively about the post-war colour bar in pubs across the country I often get asked unanswerable questions on this subject - I don’t know why racists act the way they do apart from they’ve been indoctrinated to believe in white supremacy.

The most common query is people wanted to know how pubs got away with refusing to serve customers or banning them from certain public spaces. The answer is because this kind of informal racism was never fully investigated.

Take a pub near me in south-east London: the Brockley Barge. Before it became a Wetherspoons it used to be called the Breakspears Arms and it was a building that was divided in two: it had a ‘Jamaican bar’ and an ‘Irish bar’ - I use quote marks because those were really two euphemisms locals used for ‘black and white’.

It used to even have ‘white’ and ‘black’ toilets - the latter was outside. This colour bar meant that school friends had to divide when they entered the building and Wetherspoons deserves a lot of credit for putting in a series of practices to end this kind of segregation.

Now the really shocking bit: this pub operated a colour bar well into the 1990s. I hope to cover this in full for one of the publications I work regularly for so I can’t give you any of the quotes I’ve harvested about this horrendous piece of recent history but suffice to say there’s more than a dozen accounts from numerous sources from all backgrounds.

And why was it not investigated? The police were in on it. A London landlord of colour once told me how in the 1980s he barred a racist man who threw a bottle at a black couple only to have a policeman appear with the attacker the next day demanding that he become ‘unbarred’. This is the kind of support black and Asian people gained from the authorities when it came to pub-based racism.

But there is one case - sorely lacking coverage - where a colour bar was taken to court (in similar times to when the Breakspears’s segregation was operating) and the racist perpetrators tried to justify their hatred. Because of the lack of source material there are gaps - consider this a start, maybe more people will get in touch to share their stories - but it allows us, for once, to see the worst kind of racism being challenged at its source.

This isn’t an easy read but that doesn’t mean we should ignore it. So today I want to tell the story of a working men’s club that had no non-white members in a part of Birmingham with a 60% black and brown population.

“The situation was ridiculous,” Councillor Phil Murphy told the Birmingham Post in 1992. “We had a black couple who were good friends with their white neighbours but only [the] white neighbours were allowed in the club. They could not socialise together.

“Members were left with the clear understanding that they must not introduce a black person if they wanted to stay members themselves.”

The Handsworth Horticultural Institute was formed in 1927 and operated as a typical working men’s club familiar to anyone of a certain age or who has read Pete Brown’s excellent Clubland: How the Working Men’s Club shaped Britain. It was a place people went to drink, play pool and darts but crucially they were admitted if they were members.

In order to gain membership, an applicant had to be proposed by an existing member, seconded by another and then the case would have to be heard by a committee. During this two-week process the applicant’s name would be displayed on a board for other members to see. It was said that this process was to weed out any undesirables - drunkards, hooligans - that kind of thing.

“The positive and legitimate side to it,” Pete tells me. “Is that if someone got a reputation as a town drunk, or they’re going to bring the club into disrepute, or they’re known to cause trouble then the committee has the right to say ‘we don’t want you in the club’.”

The “weeding out” process also meant that in the late 1980s and early 1990s all 1,500 members were white despite numbering 40% of the Handsworth population. This was a time when desi pubs, like the nearby Grove, were opening up because other institutions, like this one, were openly racist and segregating non-whites.

Unsurprisingly, residents complained and in 1987 the Commission for Racial Equality investigated the club recommending that it make clear to members that “ethnic minorities” were welcome, write to “ethnic minority organisations asking for applicants” and advertise in a local paper asking for non-white applicants. These recommendations weren’t even put to members to vote on by the club’s committee.

Instead the club refused to comply claiming its admissions process was not unlawful, it was standard policy of similar organisations (“and worked very well”), too expensive to consider, and the waiting list was already long.

“To say it was too costly,” remarks Pete. “Is absolute nonsense. The opposite is true because when the clubs actually gave way and became more open it was because they couldn’t afford to. They thought: The bars are empty. What are we doing excluding people?’”

“By the late 1980s I don’t think there were clubs that had long waiting lists. By that time clubs were struggling to attract people.”

In modern terms, the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) wasn’t by any means a radical organisation especially as it was headed by establishment figures. And in 1992 it saw its remit as not imposing “multiracial membership on any club” but to stop membership being denied on “racial grounds”.

Despite this chair Sir Michael Day said the kind of discrimination that the club was guilty of “would be repeated throughout the country” - which is the nearest you’d get in those days to a charge of institutional racism.

I guess the most telling aspect of the investigation was the methods the CRE used to unearth the truth. They used two sets of four “testers” - half white, half black and Asian. When the white testers entered the club the doormen were welcoming and friendly, while two of the testers of colour reported racial abuse.

I asked Pete about how common it was for a club like this to have doormen.

“They didn’t have them to stop a physical threat,” he says. “Like outside of a nightclub. The doorman would often be this old officious guy. If it became physical they wouldn’t be able to do much but they did carry a kind of authority. They would scare people: ‘Are you a member? No. Sling your hook!’”

The tests were important though as they impelled the CRE to conduct formal investigations and this is where the public body was allowed into the club to interview the decision makers. The reasons they gave for excluding people of colour were telling and remind me of the kind of garbage people say online (Twitter, mainly).

“Surely you’re entitled to your own little island, whatever your creed or colour. Until members nominate them there’s nothing we can do!”

“We’re the minority in Handsworth! Why should we bow to the majority?”

“We can’t just grab them off the streets.”

“They don’t want to join. They can’t afford it.”

“If we opened the doors not many would come. They have their own clubs.”

The club appealed the CRE’s recommendation to change its membership application policy and lost, causing it to have to alter its racist course and foot a legal bill of between £10,000-£15,000 (£22,600-£34,000 in today’s money).

I don’t know when the club closed but I can find a listing of its address and phone number on a webpage created in 2009. It’s also fondly remembered on the internet by some (white) people indulging in nostalgia. This is the only line I can find about the aftermath: “After a long struggle by the people living in the area the membership was given to black people and were allowed in the club.”

Not many stories like this have happy endings. The people of colour abused by doormen, forced to drink in different establishments to their neighbours and sidelined by bigots had to deal with the racist trauma themselves.

Racism is not seen as a public health issue - mainly because many legislators are guilty of spreading poison themselves or tolerating hate. And there certainly wasn’t a healing process as all this was forgotten and no one apologised.

But I like happy endings - I watch an awful lot of Disney films with my children and the media giant’s founder, Walt, was a white supremacist, after all. The best thing I can say about Handsworth Horticultural Institute is that it was bulldozed and its racist ghosts are haunted by the occupants of the building that has replaced it.

The desi publican of the aforementioned Grove now runs his own “Working Men’s Club” there which is a huge community building hosting Indian weddings, celebrations and events mainly held by the desi community. Because what they weren’t expecting was a generation of “invaders” to come here, set up businesses (desi pubs) and then re-invest the money into the local area.

Handsworth’s crumbling working men’s club was a pokey, racist place. But today stands something that does the opposite: the Manor Grove brings families closer in a joyous, loving environment. That’s your modern Britain - and one I’m very proud to be part of.

As an interesting side note Pete mentioned that it only became illegal for clubs to ban women until 2007 - “which is insane!”. Many thanks to his input in this article!

The headline quote is from the Joan Armatrading song ‘How Cruel’. Joan moved to near Handsworth when she was seven.