The Sam & Nam - my ideal desi pub

My favourite British-Indian public house is only two minutes from the London Overground, overlooks the Thames, and is run by Punjabi Samir Sahni. So why isn't it featured in any pub guidebooks?

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

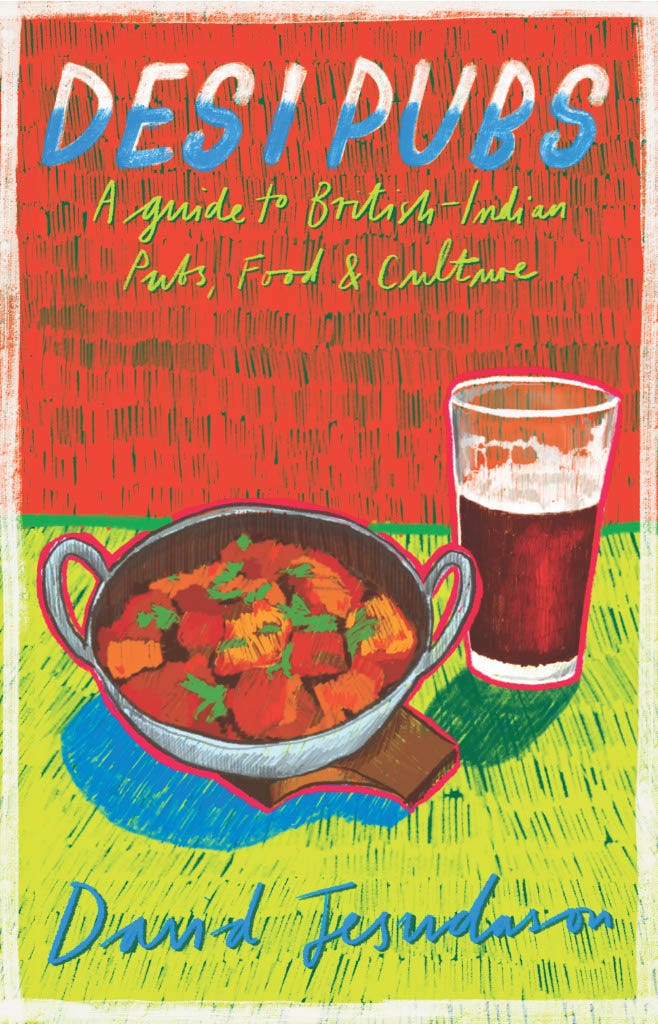

A lot of people have signed up to the free weekly email recently and there’s a question of how to support the work I put into these posts financially. I publish them to promote the book so please pre-order Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here and/or donate £3 here.

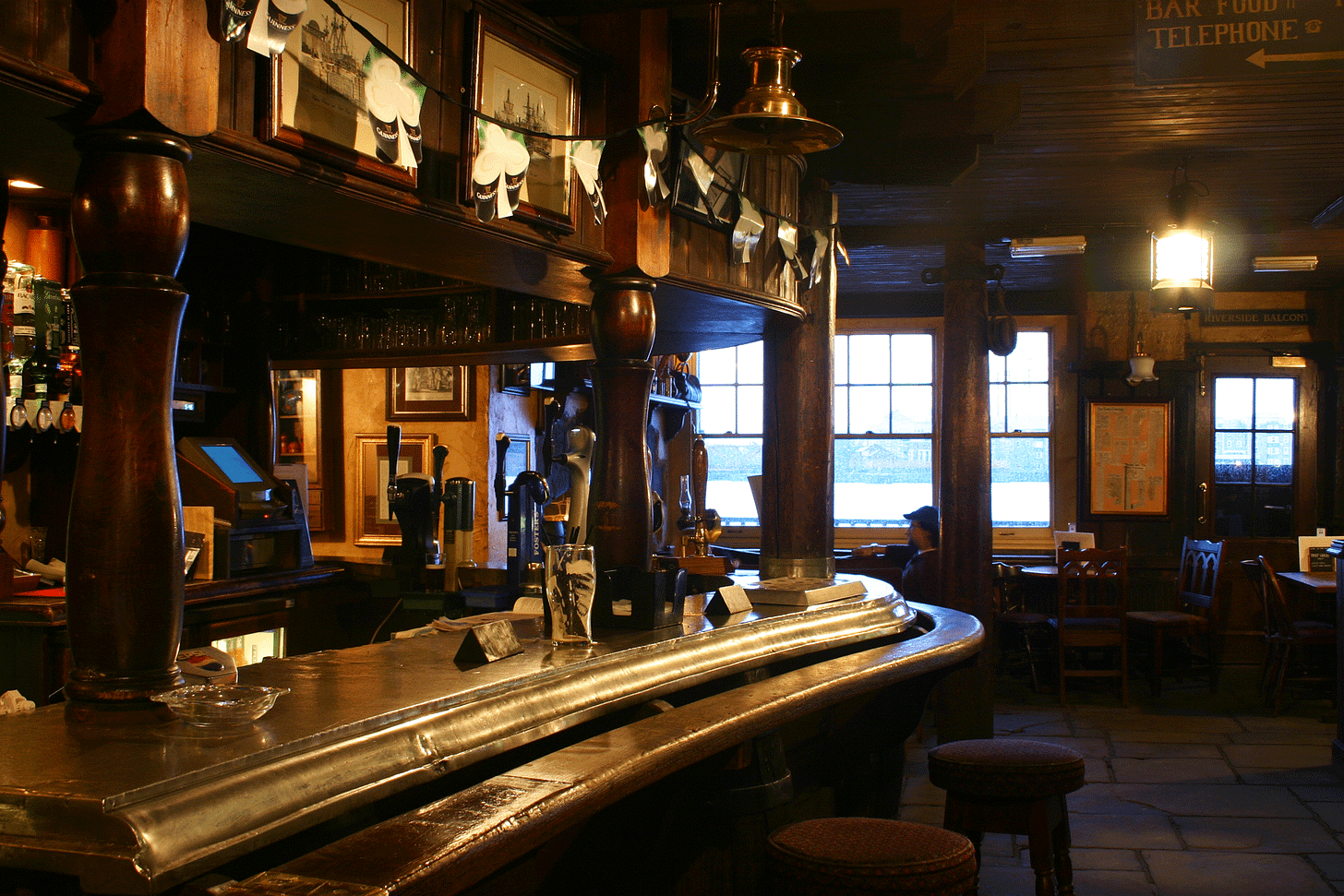

The Sam & Nam is quite unique. It has brown wooden floorboards, panelling and a long bar (with coat hooks) with a terrace that offers unforgettable views of the Thames from the north bank. It’s so close to the river that when a boat rushes past you can hear the waves lap against the sea wall. Near to the Overground (Wapping) it has a diverse clientele and when I visit there’s a mixture of Punjabi, Hindi and English being spoken.

Unlike most desi pubs, it doesn’t serve food - it’s like an old East End pub - I even think there’s a criminal element here but for the normal punter there’s no chance of trouble. If anything it means there’s always drama and the regulars have stories to tell - sometimes the gossip is from Indian villages.

For me it’s refreshing to be in a pub during the day and not feel vulnerable by being the only brown face - they don’t know my name (yet) but nod when they see me. This might change when I feature it in my book - I can’t wait for their acclaim - but it does make me feel angry that other guidebooks overlook the Sam and Nam. Which goes to show how white this type of writing is - has there every been a beer writer of the year award handed to a person of colour?

Anyway there’s always a friendly welcome and it’s genuinely inclusive especially when it comes to its hires - one of the bar staff, Gauri is deaf and is well loved by all of the punters. This is a god-tier London pub by any metric.

It was set up by Samir Sahni, a Punjabi Hindu, (the titular Sam), who went into business with Gurnam (the eponymous Nam) after he needed a loan of £10K to be able to afford the East London pub’s leasehold of £35,000.

It was Samir’s dream to run his own pub. “I want everyone to sit together and go ‘cheers’,” he said, admitting that this fantasy was borne out of being shunned from nearby Charlie’s Tavern who had a racist landlord when he visited. “Five years ago I was sent out of an English pub for my colour.”

When he opened the Sam & Nam they held a havan blessing (like in last week’s Purple Flame), which shows how the area is accepting of all faiths. As well as religion, though, the Sam & Nam is also a hotbed of politics with Samir unafraid to tackle any customer who spews rightwing bile.

He’s used to confrontation because he’s president of the Indian Workers Association (IWA), a communist organisation made famous by Avtar Singh Jouhl, despite spending long hours at the bar. In fact, he’s so busy he admits he forgets to write home and he misses his wife and children dearly but Samir has a new family now - and I’m glad I’m counted among them.

The Sam & Nam is my ideal of what a pub should be - at any rate, in the London area. But now is the time to reveal something which the discerning and disillusioned reader will probably have guessed already. There is no such place as the Sam & Nam*.

The pub - which fits all my criteria of a great desi pub - is actually cinema’s first depiction of a British-Indian boozer and all the above details are taken from the 1978 Hindi film, Des Partes (literally translated means Home and Abroad). The pub is a spitting image for the Prospect of Whitby (so much so I cheekily sent the film to some beer historians who confirmed it was the Wapping pub) but actually was a filmset in Mumbai.

I was tipped off by Steve Sailopal, founder of Good Karma Beer Company, who watched the film in the 1980s and reckoned the look of the Sam informed the way British-Indian pubs were designed. What I wasn’t expecting was for the plot and characters to mirror my research so much that Samir (apart from his gruesome fate) could be one of the many desi landlords soon to be featured in my book.

*My apologies to George Orwell for stealing this line (and the twist) from the essay Moon Under the Water. Fun Orwell fact: he would never buy a round and force people to drink the ale he liked.

1978. I was born that year. 1978. Suki Patel opened the Vine in West Bromwich - said to be the first “grill” in the area. 1978. Pollyanna's nightclub in Birmingham was forced to end its colour bar. 1978. Des Pardes was released.

It was the vision of lead actor, director and writer Dev Anand to feature a story that dealt with the fate of the Indian diaspora when they left for the “motherland”. This was a tale of first generation Punjabis having to pay criminals for false passports to gain entry to the UK and then having their humanity stripped from them.

Despite the years - or because of them - since the film’s release it’s a tough watch especially in the week a prime minister of Hindu-Punjabi descent appeared on a podium with a “stop the boats” slogan. Sunak, born two years after the film’s release, seems so disconnected from the usual fate of the diaspora and in Des Pardes they face criminal gangs who take 50% of their wages. They work jobs like bus conducting and cleaning - with only the IWA supporting their cause - far removed from a man who has a billionaire wife and a life of huge privilege.

The Indians are enticed from their villages with promises of “living like a lord in a Rolls-Royce” and “money rains over there” - nowadays they probably say “you too could be Rish!” . The only escape it seems is to own a pub and even this scheme is fraught with criminality with Samir’s partner being one of the people traffickers. This is where we depart from reality but this storyline keeps the action going with Samir’s plight being investigated by his younger brother, Veer.

In this 2014 article for the Hindu journalist Vijay Lokapally wrote:

It was on a flight that Dev Anand struck upon the idea of making this film as he read a story on illegal immigrants. Issue-based stories always caught his imagination and here was a subject that begged attention.

The use of the Indian Workers Association and a character called Avtar Singh really makes me wonder what story Anand read and based the film on. Maybe it was from the various accounts of the real-life Avtar fighting various immigration acts that barred entry from ‘Black’ countries? I only wonder as it shows how the great anti-racist campaigner inspired so many people but through his own modesty remained fairly unheralded.

It’s interesting to watch a film mainly set in England that has 99% Hindi dialogue. It’s also incredible to see a white character - played by Tom Alter - speak Hindi, Punjabi and English. At first I thought they must have dubbed it post production as it was implausible to have an actor whose accent was both immaculate when speaking in whatever language he chose.

But it turns out that Tom was an Indian, who had grandparents that migrated from Ohio, US to Madras in 1916, and grew up speaking numerous Indo-Aryan languages. He starred in many films before his death in 2017 and had a cricket-mad son, called Jamie, who followed in his father’s footsteps as Tom was also a cricket journalist - in fact he was the first reporter to interview the legendary Indian batter Sachin Tendulkar.

Because of his skin colour he often played British characters - like in Des Pardes - and famously portrayed William Dalrymple on stage in Delhi during the adaptation of the historian’s travelogue City of Djinns.

“My father was a padre [chaplain],” he was quoted as saying in the Hindustan Times. “And used to recite the Bible in Urdu. The language has no religion. I read poetry in Urdu, Hindi, English and Latin. If you love beautiful poetry, you don’t restrict yourself to one language.”

Fiercely passionate about these languages, he had to defend his Indian identity whenever anyone questioned it as this YouTube video in Hindi shows when a journalist asks him why he speaks so eloquently for a white man. His son Jamie also has to face similar prejudice when people online reckon he can’t be an expert on Indian cricket.

The life of Tom shows we shouldn’t make assumptions about languages and people’s identities based on their skin colour. Especially because someone like me who has very dark skin is completely clueless about any language apart from English (and a tiny bit of Malay).

It’s quite incredible that Dev managed to depict a desi pub so convincingly because he wasn’t steeped in drinking culture. In fact, he was a very clean-living healthy man who prided himself on maintaining an active mind - he lived to 88, just two months after the release of his last film.

“But, I am a tee-totaller,” he once told an interviewer. “I do not take liquor and I do not smoke! For my lunch, everyday, I eat only fruits and freshly cut vegetables! I try to keep my mind as creative and as optimistic as possible!”

The way he tackled people trafficking, the colour bar and a desi pub reminds me of my approach to my work and this quote explains his process.

“I see cinema in incidents," he once said. “My first directorial venture, Prem Pujari, was sparked by the 1965 Indo–Pak conflict. Then, in 1970, I was visiting a place called The Bakery, a hippie hang out in Kathmandu. And there was this brown-skinned girl swaying in the lap of a dirty, bearded, bespectacled foreigner. What’s a nice Indian girl doing here? I wondered. That girl inspired Hare Rama Hare Krishna and Zeenat Aman played her in the film. I made Censor after an unpleasant experience with our Film Censor Board.”

Whatever the case his work changed India and Britain because Des Pardes showed how desi pubs were an important part of the diaspora’s cultural DNA.

The full film with subtitles is here