Purple Flame: How Queensbury’s desi pubs lit up Metroland

Kalpesh Amlani co-founded north-west London's the Regency, ran the nearby Honeypot and Spice Rack and now owns the Purple Flame on Honeypot Lane

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

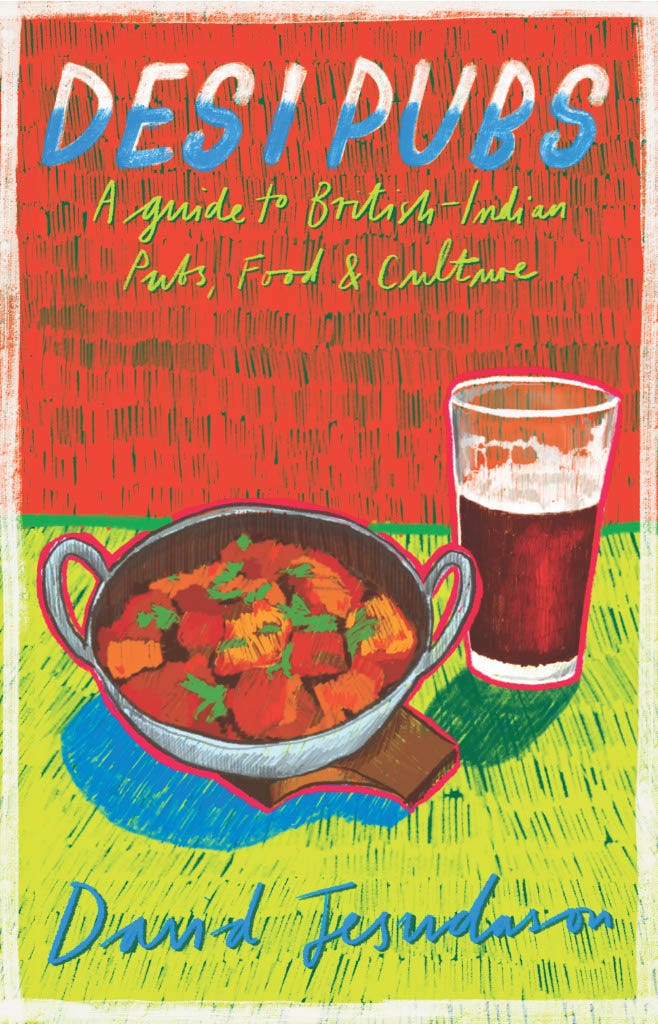

A lot of people have signed up to the free weekly email recently and there’s a question of how to support the work I put into these posts financially. I publish them to promote the book so please pre-order Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here and/or donate £3 here.

Metroland was a name given to suburban areas of Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire - and most pertinently - Middlesex. The enduring phrase was coined by the Metropolitan Railway’s marketing department in 1915 for a “Metro-land” guide aimed at walkers, visitors and, most tellingly, commuters looking for homes.

We called you Metro-land. We

laid our schemes

Lured by the lush brochure

As you can imagine, a place name cooked up by marketers was an illusionary single-identity area that didn’t really hold together as a homogenised land mass. It stretched from Baker Street to the outer reaches of Aylesbury, with the Metropolitan Railway being the only common link for these villages and leafy suburbs.

The arbitrariness of Metroland was a hangover from the way the railway was ‘designed’, which at one time had boldly attempted to link Manchester to Paris (hence Metropolitan as in Metro) until funding was pulled. It’s why the world’s oldest underground line today passes the M25 and the River Chess but splutters to a halt at Amersham in the Chilterns. The archaism continues with it even having a service that runs entirely outside London.

The poet laureate John Betjeman was the “hymnologist” of Metroland with an influential TV series inspired by his 1954 collection A Few Late Chrysanthemums, which contains a set of poems that I love for their pitch-perfect phrases and sounds.

The rhythm of his words make you feel like you’re riding with him as he revels in the tragicomedy of absurd “modern” life. I make no apologies for littering this article with quotes from the TV series and his poetry apart from I fully acknowledge he’s a snob dunking on the lower middle classes (but then so much of British culture does this).

To others, though, the area of Metroland inside the M25 that this article concerns itself with was suburban hell. AN Wilson called the pre-war houses pokey and the housewives of Neasden and Pinner as living like slaves: “No wonder, when war came, that so many of these suburban prisoners felt a sense of release.”

Today, criticism of areas, such as Kingsbury and Queensbury, has become more dog whistle and xenophobic as Eastern Europeans move in and housing gets overcrowded - “It’s sort of Metroland 2.”

Deep in rural Middlesex, the

County that inspired Keats,

magic casements opening on the

dawn. A speculative builder here

at Kingsbury let himself go, in

the Twenties.

A lot of media criticism of Metroland 2 is entirely through the white gaze of commentators viewing it through the old eyes of Betjeman, Wilson and the Metropolitan Railway marketers - it’s seen as a failure because many people are now renting not car-driving householders.

But I think it’s better. Long gone are Wilson’s bored housewives shopping at department stores, and in their place are desis queuing up for Kebabish, paan leaves (photo below) and clubs playing music into the early hours.

Scratch under the surface and this is a vibrant place where people live well and eat like kings. If you look hard enough there’s still a Betjeman beauty in the Modernist buildings and shops, usually bisected by a main road and the bustling neon-glow of the “high streets”. Perhaps it’s always been like this for a while.

Despite being derided for dullness, I was reminded by Danny Birchall that Metroland includes Music House on Neasden Lane where between 1968 and 1975 Trojan Records helped popularise ska, rocksteady and reggae in this country. (Danny, who lives in Neasden, admits that a lot of the inter-war housing is now run down but the place is diverse with most racism aimed at the Eastern Europeans.)

The real “speculative builder” - to borrow Betjeman’s phrase - of this area was a man I met this week who fled from Uganda in 1972, worked at a paan leaf shop and then set up a series of highly influential - and brilliant - desi pubs in the area. He’s the real founder of “Metroland 2” and his name is Kalpesh Amlani.

The architect Hugh Casson classed Harrow-on-the-Hill as Metroland’s capital, with others citing Wembley but today I’d argue the capital should be crowned where the Regency, Honeypot and Purple Flame sit. Fittingly, it has a regal name: Queensbury and these establishments (and the Spice Rack in Stanmore) were all in some way or another built by Kalpesh.

Out of the chimney pots into the openness,

‘Til we come to the suburb that’s

thought to be commonplace

Honeypot Lane is said to get its name from the old path’s sodden clay which would act like glue in wet weather when villagers would use this one-cart track. Before the 1930s the old road would alternate between grass and mud but the opening of Kingsbury Station in 1932 and Queensbury Station two years later caused the population to rise and mass development to take place.

In fact, the road may have been improved so that Brits could have travelled to the British Empire Exhibition held in Wembley Park in 1924, which saw the construction of the national arena then dubbed the Empire Stadium. This type of history, of course, has been covered extensively but what happened when the suburbs lost their “Britishness” is overdue an unbiased reappraisal.

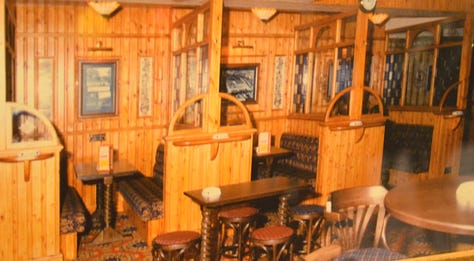

Pubs in the area included the massive Honeypot - still desi, with a shisha lounge and bhangra nights although renamed Everest Spice - and the Purple Flame, which used to be the Symphony - established 1994 - and turned into its current guise by Kalpesh in 2012.

Before these were set up a lot of suburbia merriment was expected to happen in the confines of the metropolitan (ironic, really) parts of inner London.

Cabbie has his mind on a fare to the sun

He works nights but it's not much fun

Picks up the London yo-yos

All on their own down Soho

Take me home

Blur, Best Days

This became a problem in the 1990s when the Asian community needed to find drinking spaces and the authorities didn’t really want to deal with the issue. It’s a leitmotif that features strongly in my upcoming book of the local being racist and unwelcoming to Asians and governing bodies being “unhelpful”.

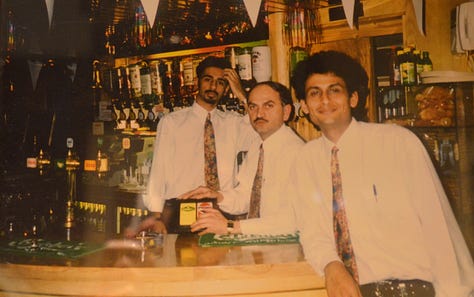

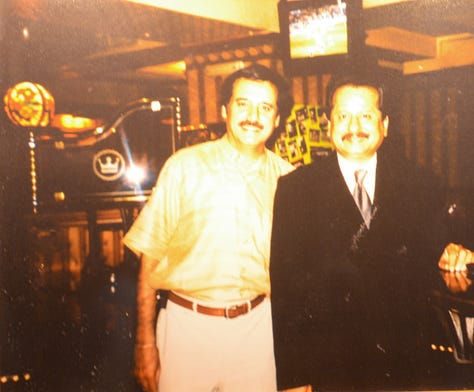

The Regency in Queensbury was set up in 1991 by Navin Sharma, Kalpesh and his brother Nilesh (who now runs desi club Trilogy in Edgware), - the first two were partners, while Nilesh was a director. The brothers’ roots in Queensbury started in 1982 when they set up Queensbury Video and Paan shop - now a minicab company next to the Tube station.

One half of this part of Queensbury is owned by the Church of England and the other by Cambridge University. Despite these establishment landlords, in 1987, they were able to move next door to where the Regency is now setting up Meera Paan House. It closed in 2010 - Nilesh has taken it over, recently apparently, and may set up a new venture.

Meera is important because this was where Nilesh was offered the two shops next door in 1991 and this became the Regency, after the brothers invited Navin to join them as he had successfully run the Premier Club in nearby Sudbury.

The council would only agree to the licence if it was a members’ club rather than a space to serve all of the community – it’s telling that in those days licensing ghettoised drinking rather than embracing diversity. The Symphony also had to be a members’ only affair - which is similar to the story to the Century in Forest Gate.

“Navin and I were partners,” Kalpesh tells me at the Purple Flame. “And we opened the Regency together. It started as one unit [it’s now massively expanded] and it used to be purely men - you never saw women. Then it got a bit modernised.”

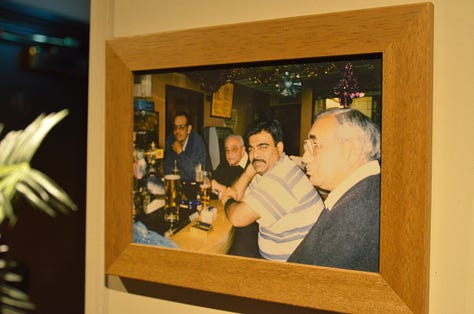

I feature the Regency in detail in my book after a few interviews with its current custodian Rahul, Navin’s son, who has taken his legacy on to the next level. In this great establishment, which is the Sharmas’ take on Kenyan decadence dining, there’s a backroom wall where old photos are displayed detailing the many people who worked at the pub - a lot of them I’ve interviewed because they learnt their trade here and opened their own desi boozers.

There must have been a sense of solidarity among Navin and Kalpesh because both were exiled from East Africa with Navin leaving Kenya in 1971 and his friend leaving Uganda a year later. Jomo Kenyatta and Idi Amin’s policy of Africanisation led many Asians to be exiled and follow similar paths to Navin and Kalpesh.

Sadly, the bond between the two was shattered and Kalpesh doesn’t even know if his photo is hung there despite this being a short walk from where we’re sat. “We fell out,” he admits. “After 19 and a half years. Unfortunately we’re not talking. It wasn’t very nice between myself, my brother and Navin.”

But maybe the schism was good for this part of Metroland as it caused Kalpesh to open the Spice Lounge - which he ran for 13 and a half years - and the Honeypot (2005-2012). The former was always very lively with a late licence (which operates today) and still is a bit incongruous as Stanmore feels to me like a typical Betjeman village despite the diversity in the suburb but Kalpesh has his own opinion.

“Stanmore used to be more affluent,” he says. “But not anymore. Now people don’t want to go to Stanmore. People still treat it like a village but it’s moved on. The people who lived there [when I had the Spice Rack] didn’t like noise.

“We used to have to go to neighbourhood association meetings - they didn’t like someone new coming in, making noise and the roads being packed at 2am.”

He lives in a flat

The linos all cracked

But he’s got plans.

Sleeper, Vegas

It’s a bit rich, I admit.

I wanted to make the point that Asian culture is always being devalued and then I write an article that has quotes from Betjeman, Damon Albarn and Louise Wener. I’m the worst offender when it comes to immediately putting white culture first and my excuse is that’s the way I was brought up. In the suburbs.

My Dad used to work in Aylesbury, Watford and Pinner. In fact, my parents met in St Albans when they first got jobs in Shenley. The M25/M1 corridor runs through me like a stick of rock and I can’t shake it away - recently I was arguing with fellow journalist Will Hawkes, who lives near me, that our part of south-east London isn’t the suburbs. (It is, I now admit, because I’m just being sniffy about outer capital places, such as Croydon).

I guess, like Damon and Louise, I’m rebelling against the suburbia of Sainsbury’s (my first job), Harvesters and the multiplex cinema (the Point in Milton Keynes, although I did see independent films when it became Easy Cinema. Great days.)

I only had white culture growing up apart from when my Dad took me to Metroland (Pinner) when he was working as a gopher for these Asian brothers who took pity on him and got him to pick up printer cartridges they made a living from by recycling.

And turning away from Asian culture is something a lot of desis are guilty of, sports journalist Mark Machado reckons. On the way back from the Purple Flame we - on the Metropolitan line - struck up a conversation about why British Asians don’t champion their own culture enough.

“The Black British identity,” he said. “Is so strong compared to the British-Asian. Asians are so used to hiding their culture in social situations. I remember countless my friends avoided playing Bally Sagoo and instead put on a Michael Jackson CD.

"I had a very left-leaning friend who was of Nigerian heritage. He said: 'Although part of me can't stand Kwasi and everything he stands for, a part of me is proud he became Chancellor’.

“We don't feel the same for Sunak, while Braverman and Patel are the most hated women in the country. I'm not a fan of the Tories and what they’re doing to this country but it's odd that we don't have the same mixed feelings."

I then argued that it comes down to class as I can’t identify with anyone of their privilege and subsequent selfish ideology - even though I know Mark believes the class system is something British-Asians should keep away from. And he’s right as this classicist prejudice is one reason why the brown movement has little solidarity - which is just what people like Patel, Braverman and Sunak thrive on.

Whatever the case, we should champion tangible British-Asian success where we see it and the achievements of the Amlanis and Sharmas are definitely cause for celebration because they show you can start an exciting life again and again. Africa. England. Queensbury. Uganda. Kenya. London.

The Purple Flame is the only bar Kalpesh is left with. But that doesn’t mean he’s slowly giving up serving booze and curries - far from it. The night Mark and I visit he appears later on in the evening despite the bar staff telling me I’ve had a wasted journey. We watch him work the room while the football plays and the grills sizzle.

Kalpesh is the type of publican that causes his customers’ faces to brighten as he remembers their family and the good times they’ve shared. I tell him about my book and when I ask him for a chat he says “of course” and I’m given instant access to his world - the ultimate privilege - where every question is answered truthfully and thoughtfully.

It turns out that he’s a self-taught cook and recently started experimenting in the Purple Flame’s kitchen - the name by the way has no real meaning. “Four of us sat down and just started bombarding words.”

The dishes Mark and I chose were purposely different to other desi pubs - we’re coming to the end of the adventure as my deadline looms and variety is important. We have Methi Gota with onions - round balls possessing a dry heat which demonstrate the chefs’ skills with heat, potato; Chilli Aloo and “Atomic chicken” - chicken pieces on the bone cooked in a fiery red chilli sauce.

“That’s why it’s called Atomic chicken,” he laughs. “We’ve got different levels: chilli chicken, green chilli chicken and Atomic chicken.”

There’s two notes of sadness when I speak to Kalpesh. The first is his partner at the Purple Flame, Sam Desai, died at Christmas. He was 44. “It was tragic,” Kalpesh says. “He was with me for 27 years. He was a barman at the Regency from 17 years old.”

Other people have used the Regency as a stepping stone, such as Abhi Paudel, who owns the Fishponds in Bristol and is thriving. He started working as a bar manager under Kalpesh - the Regency is a great apprenticeship for desi landlords because anyone everyone learns the entire business from bottle washer to front of house.

The second wistful theme is the shrinking empire. Kalpesh says it’s the wrong time to expand because rising costs means profits are a lot lower because ingredients’ prices keep rising - he’s subsidising his customers basically (a common theme recently when I’ve spoken to desi landlords). He’s already had to raise what he charges once and if he does it again then footfall will be affected, despite having a range of core regulars who visit most days.

I ask him, though, what it feels like to start so many businesses and give so many people a chance in the industry. He answers: “The best thing is the buzz.”

I have photos of the Purple Flame and Alpesh but I’ve forgotten my camera’s lead an I’m in Newcastle.

This week I’ve mostly been reading Hancock’s WhatsApp messages. What a ****. See you next time!