Once they accept you, no one will touch you - Century Club, Forest Gate

Peter Patel set up a special bar for Asians in East London in the 1980s offering a very different experience to any other desi pub of the time

Disclaimer: this post mentions beer and pubs frequently. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

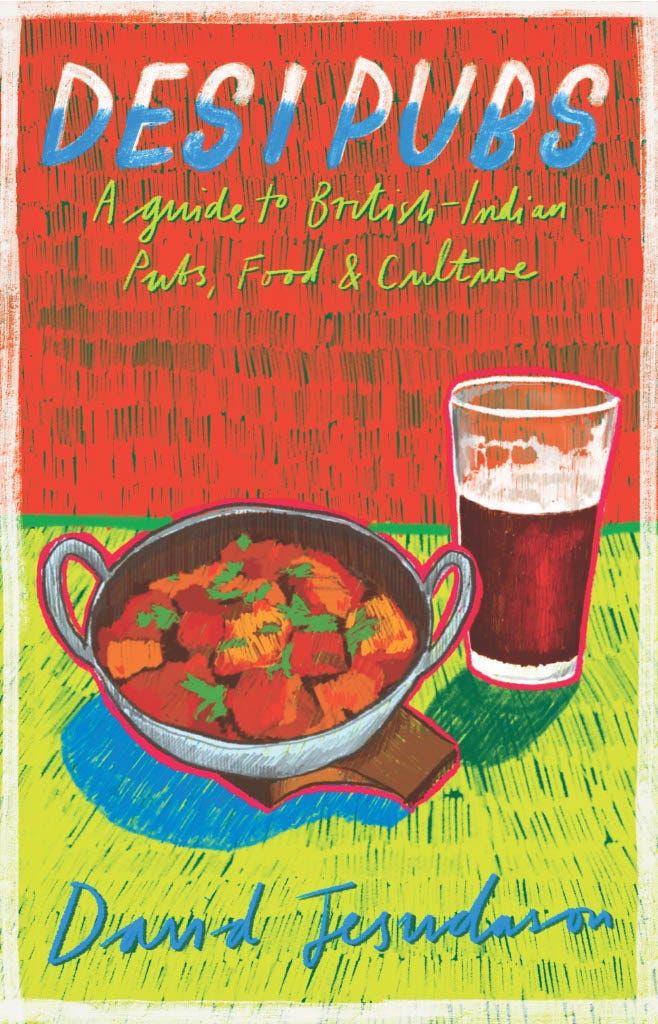

You can pre-order Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here

When Steve Sailopal, founder of Good Karma Beer Co, last week told me that he - like his father decades before him - couldn’t visit pubs in the East End in the 1980s as they were racist, dangerous places that were hostile to Asians, I knew this was a story I wanted to tell in full.

Steve’s father, Lachman, in the 1970s lived in Bow and had to travel to Epping, Essex, where a landlady would serve him and his cousins. Steve even remembers seeing a picture of his elder family members wearing smart clothes visiting this pub. For Steve, not much had changed when he himself was old enough to set foot in a licensed premises. All the East End boozers were racist and his nascent drinking life was blighted by prejudice and the threat of violence.

Except one place - an Indian club called Century at Forest Gate that served sizzling chicken tikka and shish kebabs. Steve visited it in the 1980s with his elder brother and to my amazement (and joy) it still exists today with a new owner who not only remembers fondly those halcyon days but was part of a regular crew.

He, Mukesh Kanbi, put me in touch with the original gaffer, Peter Patel (his birth name is Pankaj but prefers Peter) and I spoke to other Century Club drinkers who found it a vital safe space that was different to the point where the venue even confounds some broad beliefs often held about desi pubs.

Not only do all the people I speak to remember it as a special time with Asians travelling from all over the country to visit but one that’s sorely missed as this part of East London changes.

And it all started at a Croydon laundrette in the 1960s when Peter was just 12 years old.

“In those days everything shut at 5pm,” Peter says. “The laundry would open until 9pm. Next door was a pub which had a piano and I was always fascinated why everything was closed and this pub was open.

“Through a swing door I could hear people laughing and see them smoking, drinking and enjoying themselves. I thought: ‘I want one of these when I grow up’.”

Peter’s Hindu family is from Kenya and they were all vegetarians when they left the African country - I mention this as it was difficult in those days for anyone to be a vegetarian, not just a member of the Asian diaspora, and Peter had no choice but to eat meat at school.

The Patels initially started their new lives in Croydon, eventually moving to Mile End Road, East London in 1972. But the memory of the pub next to the laundrette stayed with Peter so much so that when he passed his driving test in 1976 he took his friends to the outer London town to find a pub that was similar to his childhood recollection.

“We went to the Wheatsheaf,” he recalls. “We didn’t know that in the evening it used to get bikers coming in and they chased us out.”

Peter faced similar prejudice in those days when he visited a pub with friends in Lewisham, South London, where I now live. A racist purposely spilt his drink on him, claiming Peter had tripped him up and demanded more than another drink. The atmosphere turned rancorous, the publican sided with the attacker and the Asians were kicked out despite already spending about £40 (the equivalent of £300 today).

“It was a lot of money as a pint used to be under a pound then,” he says. “We did nothing at all. That’s when I decided we needed something for Asian people. Not many Asian people went to the pub - it was mainly white people. When we went most people were all right but one or two wanted to pick a fight.”

Not only fights but shootings. And it seemed fulfilling his lifelong dream of setting up a pub was difficult. In those days, Peter recalls, licences were only given to wet pubs and he wanted to serve Indian food and when he applied the relevant authorities said the venture sounded more like a restaurant.

“Indian people,” he says. “Don’t want to go to the pub and have a curry afterwards when the pub is closed. They want to eat with their drinks. There was one club in Wembley [called Premier].”

Watneys bought into the idea that running an Indian club/pub was feasible from the example set by the Premier in Wembley and even agreed finances with Peter but the brewery’s volume demands were too high. Instead he went to the bank for the money which allowed him to set up a freehouse and run things the way he wanted.

He chucked in his job at a newsagent and in 1988 he set up the Century Club but there was one group that he wasn’t prepared for: Asian gangs.

Peter may have risked groups of bikers in Croydon and racist landlords in Lewisham but his tenacity to provide something safe led to a band of loyal customers, which was the perfect riposte to all this prejudice he had experienced. As someone who’s first pint was in a racist pub similar to the ones Peter endured, I love the idea of a brown person’s beer initiation being in the opposite type of place - a venue that is full of fun, life and free of hate.

Especially if that person is older than me, which shows that my horrible market town pub experience with people shouting ‘taxi’ when I walked in wasn’t ubiquitous, wasn’t universal.

Hitesh Joshi is now 57 years old and is visiting the Century during the Arsenal v Man U match on 22 January with his twenty-something son Neil, who is a Gooner, like me (and Steve Sailopal). “We’re absolutely going to win the league,” Neil tells me as his United-supporting friend storms out in disgust. Wait. Is this an Arsenal desi pub? Few care, I guess. Well, I do.

Among the chaos of the match and the banter at the bar (I got carried away when the winning goal went in, jumping from my seat) Hitesh is a calm, laid-back presence. He’s seen it all before and probably realises his son’s (and mine) excitement will dissipate when Arsenal’s title push runs out of steam. Or maybe he’s just savouring the passing of time in a special place.

“My first beer was a shandy in Cornwall,” he says. “But my second beer was here. Not only do I come with my son now but I brought him here, with my missus and my daughter when they were quite young.”

This is quite a surprise. Because the first desi pubs were traditional hard-drinking male environments and it’s rare to find somewhere that the whole family was welcome. At first I attributed this to the place being run by a Hindu and frequented by desis of a similar religion - later Bollywoods (set up by boxing ref Jumbo Bassi then run by others) opened nearby catering for a Punjabi crowd. But Peter says all types of Indians drank here - including Muslims - and the idea of Hindus being more reserved than Sikhs is probably a myth.

Whatever the case, there was something safer about the Century. “The white guys who drank in here were police guys,” claims Neil.

Ah. Now this is something that makes sense when I walked past Forest Gate police station to get here. But the story of the police involvement was by design and something that Peter sought to guarantee the success of the venue that saw people travelling from as far as Brighton to visit.

“In the Indian criminal world,” Peter says. “We were known as a police pub.”

He breaks into laughter but the reason behind this was necessary for survival. When he first set the bar up he would be approached by Asian men for protection. “I wouldn’t say it was organised crime,” he says. “More a bunch of thugs getting money off the Asian businesses.

“The boss will send all of his lackeys in and then he would come down to my club like he’s not associated with these guys. He’ll say ‘Give me £500 or £1,000 and I’ll make sure they never come down again’. But I’d been living in East London since 1972 so I knew what the score was.”

Peter then tells me of a similar situation where a desi pub owner in Wembley ended up being ruined by the same racketeering and how he ended up dying prematurely through alcoholism. So you would imagine to solve such a problem a radical solution was needed.

“How did I stop them? By not being scared of these guys.”

The atual answer was to hire a bartender called Kathy, whose husband was a special surveillance officer. He helped organise a couple of plain-clothes police minders who would protect the business and they had to be Asian officers so they could blend in with the desi crowd.

At the time Peter was the cook at the Century and he fed his CID minders from a small kitchen (which has since moved to the back of the building). There never was a menu just Indian food cooked to order.

“Everyone wanted to work the nightshift at the station,” he says. In fact, the Century got such a good reputation with the police that they used to hold their leaving dos there.

When I walk to the Century Club to meet sports journalist Mark Machado I pass the police station and then numerous shops which could be the Century at first glance. I’m a bit discombobulated after being asked by a guy with a strong Indian accent if he can cross the road - I’m assuming it’s his first visit to the UK and he’s worried about jaywalking laws. I say yes and then seconds later hear a car screech behind me.

When I arrive I’m slowly buzzed into the ‘club’ - you don’t have to become a member these days - and sit in the modern, rejuvenated establishment. It’s plush and full of glass features - I’m later told by current owner Mukesh that the reason why is that he owns a glass factory.

These days everything is more relaxed but the food is top notch. Mukesh admits to me he took the place over so he could keep a venue that the uncles could meet in to exchange stories of the old days and where he could host business contacts as well as playing cards with his mates.

We order a few staple dishes - I particularly enjoyed the tandoori prawns from the menu. Mukesh tells me I can ask for what I like similar to when Peter was the chef, something that might not last when he hires a bar manager who can publicise this great place as more punters means a busier kitchen.

It’s not making him money but then that never was the entire point of the Century. Peter stayed for 30 years (he had a 15-year lease he renewed once) and towards the end it was difficult as his wife had a stroke. He also had to compete with other Asian bars and clubs, such as Bollywoods, William the Conqueror, the Rising Sun and Gymkhana in Ilford.

Many have closed but the Century is still there: Britain’s first desi police pub.

Next week I explore how inclusive desi pubs are for women.