El Vino, Fleet Street: 'the sexism and exclusion was so petty'

Anna Coote took on the misogynists and details the fight to end sexual discrimination in bars in the UK

These articles are vital and entirely funded by me, so please donate here to continue to support similar investigations. If that link doesn’t work for you (or if you’re paying by Mastercard) then you can also use my Ko-Fi here.

I am a journalist who writes for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

I’m offering my book, Desi Pubs, at Amazon prices. I can have it sent to you very quickly for £12.29! Message me on Bluesky for copies. There’s a review of it here.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

Today’s Substack is about how the fight to end sex discrimination in public bars resonates with the battle to end the colour bar. Not only do the parallels demonstrate how making pubs and bars more inclusive changes wider society but the methods to do so by campaigners were very similar.

Peaceful but brave tactics were required in the face of ignorant racism and - in today’s case - sexism.

And because of the relatively recent campaign one of the main protagonists was more than happy to speak to me about how she and her fellow feminists helped change the law - and crucially - helped enforce it.

Usually when I delve deep into the past to look at how exclusion was ended I have to rely solely on archive material unless I’m given unique access, such as this article about Avtar Singh Jouhl. So it's an honour to speak to Anna Coote who took on the sex discrimination at a central London pub, El Vino, and won.

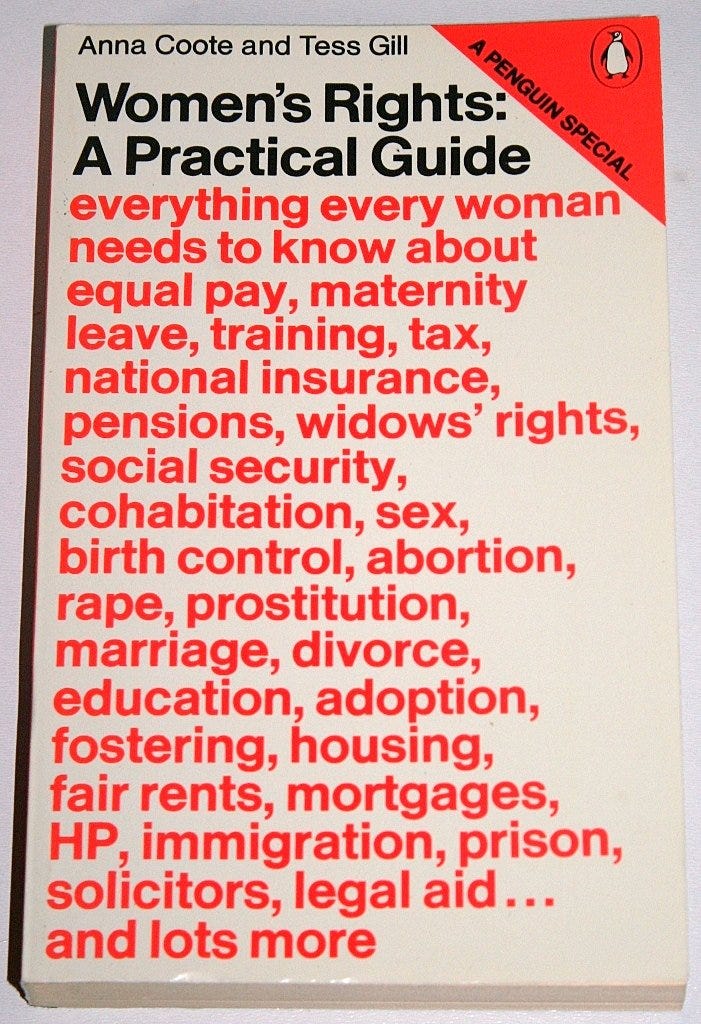

She - and feminist comrade Tess Gill - firstly led the fight to outlaw discrimination by campaigning to get the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 passed and then made sure that the law was enforced by taking El Vino to court and winning their case successfully in 1982.

The El Vino case explains how sex discrimination in pubs became illegal - worth noting, though, that private member clubs were (and still are) allowed to ban women - and how this eventually opened up (most of) British society to all.

When you come out of the north bank side of Blackfriars station and walk to Fleet Street you can’t help but notice the position of wine bar El Vino and how it’s a gateway to the City and Temple.

It has a modern frontage and is now part of the Davy’s chain, but its ornate sign hints at a past when its convenient position would entice Fleet Street hacks, politicians and lawyers to use it as a vital part of the old boy’s network.

This was an archaic past, though, and all these influential people were ‘old boys’ because even into the 1970s, it was a bar that had misogynist rules set by owners, Tory MP David Mitchell and his brother Christopher, and enforced by manager Paul Bracken.

“Senior QCs drank there and big-shot journalists,” Anna tells me, “and so did the women but the women had to sit down and get their drinks bought for them at the bar, and brought over to them and they weren’t allowed to stand.”

Their defence was that it was “old-fashioned chivalry" despite El Vino being accused of a male club masquerading as a pub. Christopher Mitchell even told a licensing renewal session in 1977 that women “were treated with decency and courtesy".

This risible defence led to numerous protests including the visit of a group of 50 feminists called “Women Against Chivalry” who entered the premises in 1978 wearing suits, ties and false moustaches leading to the bar being shut and the police called.

“El Vino stood as a symbol of an ordinary drinking place,” Anna Coote tells me, “that wasn’t a private club and they were not letting women buy drinks at the bar which was very petty of them. But at the time the men were hanging on to their control over how their favourite pub was being run.

“And it wouldn’t have mattered half as much if it hadn’t been the place where lawyers and journalists [met] - because Fleet Street was still operating at the time and the newspaper offices were there.”

***

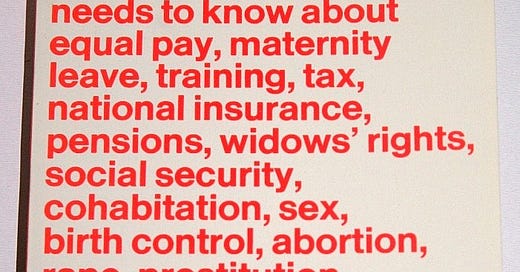

Anna and Tess Gill had written the influential Women’s Rights: A practical guide, in 1974 which sold very well and soon became a Penguin Special edition.

It established them as prominent campaigners and had given Anna confidence to push hard on campaigns, one of which was the need for Parliament to legislate against discrimination on grounds of sex which many feminists demanded.

“I don’t think I was hounded out of places for being very radical,” she says. “I was surrounded by like-minded people and it wasn’t a hostile environment. [The Sex Discrimination Act] was a big part of my life at the time.”

When the act was passed in 1975 the women’s rights campaigners recognised the new law would only be fit for purpose if it was tested in court because some parties - such as El Vino’s owners - would outright flout it.

“We felt [the law] was a turning point,” Anna says.

The law outlawed discrimination in terms of employment, education and access to goods, facilities and services - the latter was where El Vino was at fault. However, like race legislation that banned the colour bar it made discrimination a civil matter so it relied on victims of discrimination to take legal action.

I believe, albeit in hindsight, this led to colour bars operating in plain sight, such as this one, as those marginalised often feared the law but Anna disagreed that it should’ve been a criminal offence.

“I think criminalising sex discrimination,” Anna says, “at that point when people barely knew what it was [was wrong]. It was about what was right at the time and even to this day I’m not sure I would want to criminalise sex or race discrimination of itself. You need to outlaw it and you need to have a means of address.”

In any case the Equal Opportunities Commission backed the side of the women’s rights protestors and Anna recalls how this was received in the press with some saying the commission based in Manchester should change its address to ‘Personchester’.

Her involvement with El Vino began when she was approached by Tess, who was a lawyer and wanted to test the new act in court. Tess had the necessary legal contacts and the duo employed a barrister.

They used the El Vino as a way to change the law and they didn’t see themselves as patrons of the bar. Anna says they went to El Vino with a couple of male lawyers and were refused service and this was all the proof they needed.

“It was to get the law enforced not to get drinks at the bar,” Anna tells me. “It was purely a matter of principle. Neither Tess nor I wanted to spend a minute inside El Vino’s drinking wine or buying drinks!

“It was to make sure this symbolically important pub was available to women if they wanted to. And they shouldn’t be ignoring this new piece of legislation that had come through in 1975.”

Other parties were taking other cases to court to test the 1975 act, such as discrimination at work, but this was the first action in the section of the act on access to goods, facilities and services.

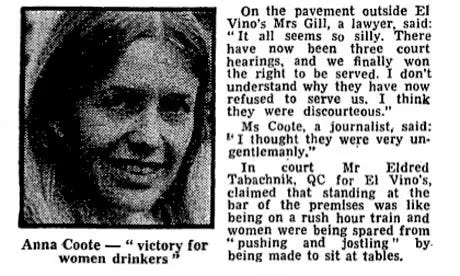

After failing in the courts in the 1970s, it wasn’t until November 1982 that Anna and Tess won their case at the Court of Appeal forcing El Vino to end its sexist practices. Days after the verdict El Vino lifted its lifetime ban on Anna and Tess - not that they were minded to drink there.

“It feels like a long time ago,” admits Anna, “but things have changed rapidly [since]. They have and they haven’t - certain things you’re still not allowed to do but then things happen in a different way. I think white women have had a better deal of it rather than women of colour.”

Perhaps how much things have changed were shown when Anna visited El Vino with her husband for drinks when they were invited by the new owners.

“There was an Australian barmaid,” she laughs, “and it was just completely different.”