The Lamb, Lamb's Conduit Street - time to play the polyphon

Artefacts of segregation - AKA segregationana - are among us and this is no bad thing as my time at the Lamb in Lamb's Conduit Street shows

If you like this story and want to support similar ones on this subject please donate here. If that link doesn’t work for you then you can also use my Ko-Fi here.

If you’ve not done so already please buy Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here - hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years” and winner of the British Guild of Beer Writers best book 2023.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

I am a journalist who writes for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

Sometimes the perfect antidote for the trauma of the past is the present. After publishing numerous incidents of segregation in pubs, the last one demonstrating how this racism was class-based, I haven’t explored how certain artefacts of exclusion reside with us today.

Maybe I should create a new word for the phenomenon of segregation artefacts: segregationana. And today’s pub has plenty of that and much more. But these relics show that this isn’t something that can cause us pain - in fact it can be the opposite.

My book presents many examples of former segregated pubs that have now become not only welcome to non-whites but are run by desis and are inclusive for everyone, regardless of race. Previously, non-white patrons would either be not served or be told to drink in the public bar. But now these spaces are the opposite with little nods to the past of how class-ridden Britain was.

And was is the key word here. Because although it would be politically convenient - and wrong - to say class (and logically racism) doesn’t exist in Britain in 2024, it is the case that some of us can live lives not entirely ruled by the notion of being discriminated against because of our background.

Or maybe I was just in a good mood when I visited today’s pub, found a nearby archive and wrote this piece.

Lamb’s Conduit Street is one of London’s great thoroughfares. On a concrete-grey autumn morning, it still somehow retains the feel of a country lane and a village vibe despite the daily migration of hired e-bikes.

According to John Conen in Holborn and Bloomsbury Revisited, Lamb’s Conduit Street ‘is living proof there still is community spirit in Holborn’ and you can feel it in the surrounding houses and the people who reside there.

I bump into 82-year-old Violet who tells me about hiding doughnuts from her son who is worried about her diabetes. I see the families walking to nearby Coram Fields and, less quickly, to Great Ormond Street Hospital.

The workers slow in step before they join the bustle of High Holborn, like they are flowing against the tide of the ‘conduit’ of Conduit Street brought to the area by Sir William Lamb in 1577 - perhaps the first act of aforementioned community spirit when Lamb ‘gifted’ 120 buckets to poor women to sell water.

This is the place to be not behind a desk.

It’s 10am and I head to the Lamb to speak to general manager Ralph Parham who runs the Young’s pub with his partner William Morris after they moved here a year ago from the Old Red Lion in Kennington. I wait in the dark for the staff meeting to end and then Ralph turns the lights on. The show begins.

I’m here to see the Polyphon, a Victorian music box, which fills the air with a tinkling tune which feels to me contradictorily both innocent and sinister when Ralph winds it up. It used to be operated by coin - a token - which was given to you if you made a donation, but now it only works this way. I recorded this video of it.

“If it’s a busy Friday night it doesn’t go down [well],” says Ralph, “but Saturday afternoon if people are interested we give it a little go when it comes up in conversations.”

Ralph shows me about 20 or 30 different tracks in a cupboard. These are giant metal discs with punched holes and Wikipedia describes the mechanics of the musical process:

When the Polyphon operates, the resulting disc projections, called plectra, engage with a series of ratchet-like star wheels, each with nine projections, that sit in a gantry. Each star wheel, when moved through 40 degrees on its axis, plucks a tooth on the instrument's comb. The tooth resonates, sounding a predetermined note.

“It’s kind of like a mechanical, circular harpsichord,” concludes Ralph. “In Victorian times people would sit around and listen to this - what else would you do! This might be a rumour but the current track is a death march and one of the general managers had a friend die and she put this on as a tribute.”

A dirge before my first pint.

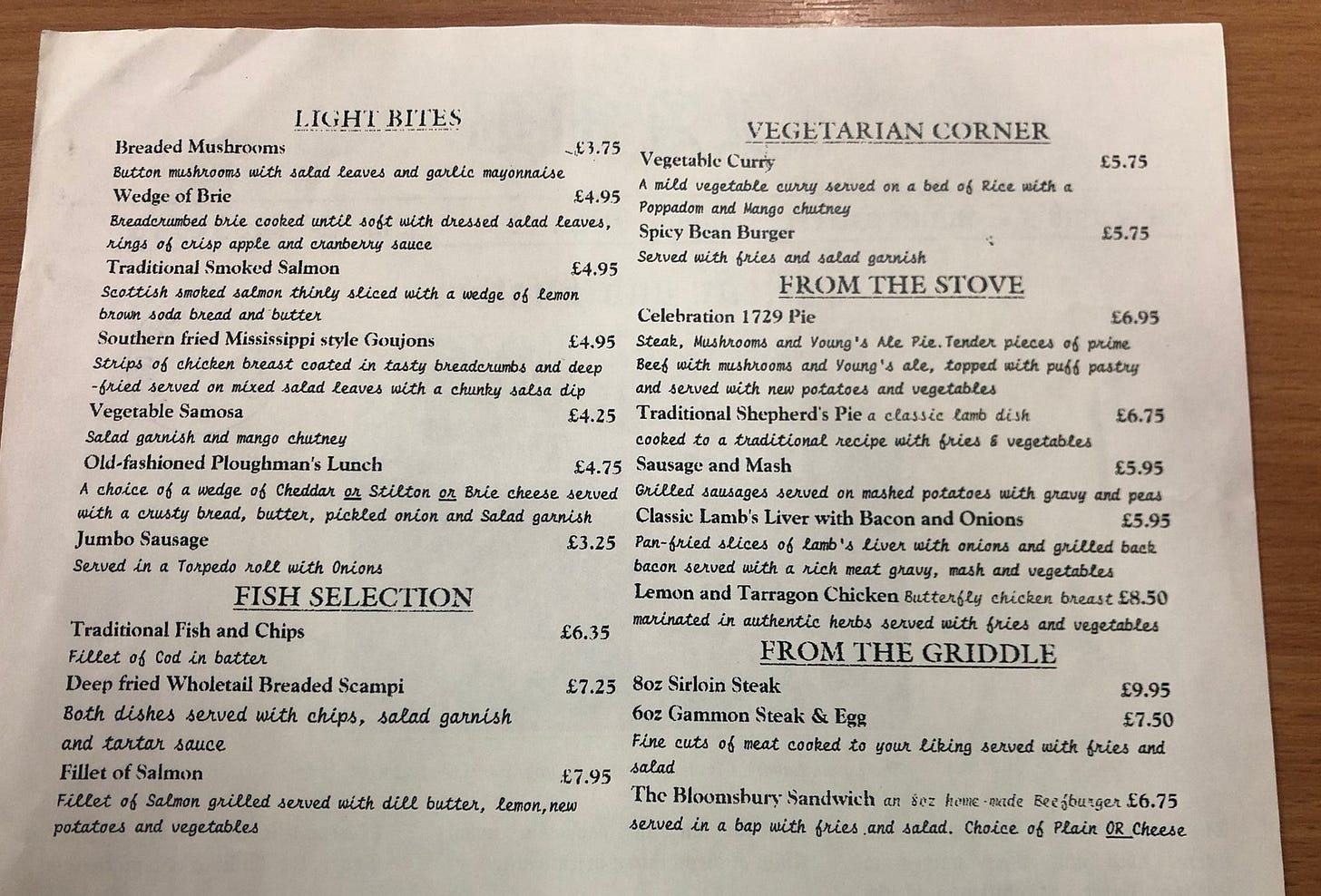

A photo of the Lamb I found taken in 1986 shows little has changed today with the exceptions of carpeted floors, metal-railed tables and Beamish. Today there’s the same amount of cask pumps and William points out this is the second-most successful real ale Young’s pub, behind the Lamb and Flag in Covent Garden. (More on cask ale’s plight here from Pete Brown).

In 2024, there’s so much history residing in the Georgian building on the walls, bar and doors. The 1890 photos of musical hall greats who once appeared at the now demolished Blitz-hit Holborn Empire. A barrel of “Morueco Amontillado Sherry”. A frosted glass Lounge sign.

But it’s the snob screens in the Lamb that are the biggest hint to its prejudiced past when middle class drinkers wanted to shut out others from their view. I take a photo of Ralph through one and he’s keen to point out how they not only affected those deemed lower classes but even the Lamb bartenders.

“They could have privacy not just from the other side of the pub,” says Ralph, “but from the bar staff as well. You open it to order your drink.”

The pub had a revamp in 1956 when Young’s took it over, previously it was a cider house, and Ralph reckons the snob screens survived and still have the original 170-plus-year glass.

Ralph finds it amusing that as a gay person he’s living and working among all this archaic segregationana.

Especially because he got some unexpected abuse for hosting events that made members of the LGBTQ+ community welcome. And here we are mindfully listening to a harpsichord-sound tinkle in the background among the snob screens of the Lamb.

Because pubs like these might have been segregated and a hotbed of class warfare but now they’re just here, living and breathing their inclusion. But it’s a busy old place and Ralph needs to crack on and serve the lunchtime crowd who drown out the sound of the past unaware they’re walking through a museum of segregationana.