Dartmouth Arms, Forest Hill - Fighting for different versions of the future

The 1960's colour bar at the Dartmouth Arms helps to explain segregation in British pubs

If you like this story and want to support similar ones on this subject please donate here.

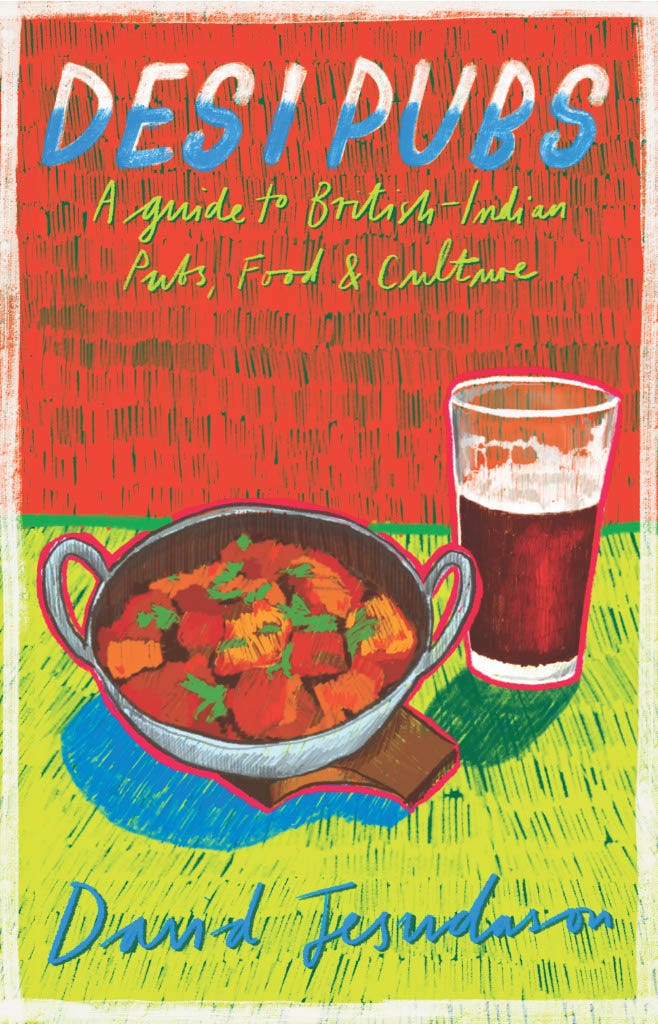

If you’ve not done so already please buy Desi Pubs - A guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food & Culture here - hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”.

Disclaimer: this newsletter often mentions beer and pubs. You do not have to read this if your life has been affected by substance abuse.

I am a journalist who writes for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. I was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023 by the British Guild of Beer Writers.

The last few articles I’ve published here have been about racist issues in pubs and clubs, such as the colour bar, and the various groups who took on the fight against segregation and exclusion. I feel like the stories transcend their setting and are a lot more than a social history of drinking.

They act as a kind of beginners’ guide to how society took on prejudice and provide valuable evidence to how we now have - and still need - inclusive practices and laws. Boak and Bailey recently said they “reveal the history of racism in Britain through the lens of pubs and beer”.

Last week’s post wasn’t really about an offensive pub sign itself but it was about the fight to remove it and how radical street-based politics sometimes can sway those in power. We need to recognise that all the inclusive policies and rules we abide by came out of this fight especially because the hard right wants us to forget this.

They want to obtusely argue that any objection to exclusion or prejudice is part of the culture war and/or us being snowflakes. Now you tell me if the heroes who took on the racist sus laws were snowflakes?

But when it comes to the colour bar I don’t think I’ve delved too deeply as to why they existed and who perpetrated them - or the conditions they thrived in. This is why I often get questions from people completely flummoxed that segregation would exist in the UK in towns and cities they lived in.

(NOTE: Just because it’s illegal, though, to refuse service to anyone on grounds of race, gender, sexuality etc it doesn’t mean it still doesn’t happen.)

I do feel that more context - or indeed some context - is needed when it comes to the colour bar.

There’s two simple reasons why I don’t present a fully rounded explanation as to why a publican banned non-white customers from certain rooms. Firstly, I don’t want to give racists a voice (and when I do they only sound even more culpable). Secondly, there’s very few reliable sources as to why whole communities wanted - or if I was being generous - tolerated segregation.

But a few researchers and academics, such as Rob Waters who I speak to today, have delved into these thorny subjects to give some much needed explanation as to the practicalities of historic segregation in the UK. (NOTE: this Wikipedia page didn’t exist until I created it, which shows this is subject even historians want to forget about. It even has an example from 2022.)

There are also a few colour bar cases that were so well-known and well reported contemporaneously that we can use them to explain how segregation worked in the past.

The first is the Blue Gates in Smethwick, which Malcolm X visited with Avtar Johal Singh, which I’ve written extensively about, not least in my book. The second is walking distance from my house: The Dartmouth Arms in Forest Hill.

The colour bar at the Dartmouth Arms in Forest Hill was well known in 1964 and grudgingly allowed by owners Courage, Barclay & Co.

After a report of segregation it gave this obtuse comment to newspapers: “Of course we don’t apply a colour bar in any of our businesses. In fact, we are dead against this sort of thing. We in fact employ a great many coloured people in our breweries.

“But the management of all our pubs is left to our landlords, and it’s entirely up to him who he serves.”

The Dartmouth’s landlord was Harold Hawes who would tell non-white customers to drink in the public bar and leave the saloon if they dare enter. The context here is this is as much a class-based issue as it is a race one because Hawes barred people from the saloon if he deemed them not worthy or respectable.

Britain at the time was a fiercely hierarchical country even before you put its empire’s subjects into the mix. So for someone like the racist Hawes to equate colour with being lower down the pecking order, wasn’t a huge jump in his muddled thinking.

In effect, he was conforming with everything he had been educated and socialised by despite living and breathing examples to the contrary entering his business and wanting to be his customers. He as much as his non-white customers was a product of empire, which divided on grounds of colour, race, religion etc.

Which doesn’t fully explain why he said: “I object to coloured people drinking in my saloon because of improper behaviour. They have quarrelled with each other, and I have seen them putting their arms around the necks of white girls who have resisted.”

He also claimed a coloured man threatened to throw an ashtray at his wife.

“One way of reading it is,” Rob Waters, senior lecturer in modern British history at Queen Mary University, London, tells me, “is the impossibility of these publicans imagining black or brown respectability. I guess they kind of thought it was obvious that people of colour would go to the public bar because they couldn’t be respectable enough to be in the saloon bar.”

The saloon bar in a class- (and race-) segregated pub was often more salubrious - nicer furnishings - and the drinks were often more expensive. In 1964, some pubs had this multiple-roomed-class-based segregation but still refused to serve non-white customers at all but Dartmouth Arms operated what I would call a classic colour bar.

Rob says that these class-based distinctions were prevalent in the 1960s, especially in literature of the time where the protagonist of the novel L-Shaped Room wanted coffee shops to be segregated like pubs, so she could avoid the riff-raff.

And these class distinctions were also firmly embedded in the minds of the people who found themselves subject of the colour bar.

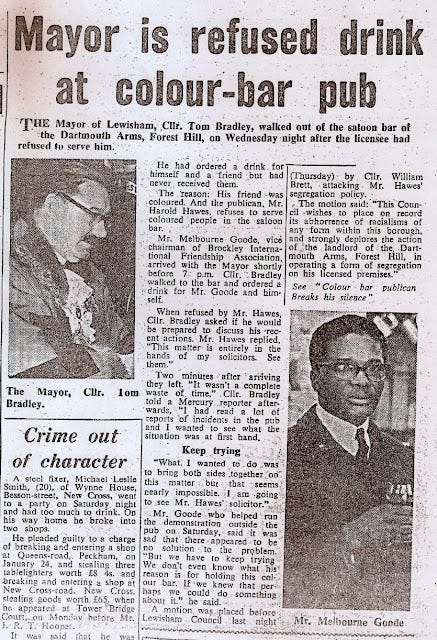

In September 1964, Geoffrey Browne 34, a Lewisham company director, found himself subject to the colour bar at the Dartmouth when he was told by Hawes and a reporter at the Sydenham, Forest Hill & Penge Gazette: “Sorry, I don’t serve coloured people here. You have to go to the public bar.”

That same month, Browne, McFarlane and manager of an employment agency George Brown, 53, of Brockley, manager of an employment agency visited with a Hong Kong-born Sydney Hollands, a 36-year-old journalist.

“I accompanied the four men into the lounge bar and ordered drinks,” says Ken Vass. “The barman would not serve me.” Hawes was called. He refused to explain why he had barred coloured customers and said: "I can refuse to serve anyone I like. If you want a drink, you will all have to go to the public bar."

“Hawes then ordered us to leave. No one moved, so Hawes went out. He returned a few minutes later and said he had phoned the local police and complained that we were causing a breach of the peace. The police had not arrived after half an hour so we left.”

Brown said: “I have been in England for 10 years and this is the first time I have met this discrimination."

It’s unlikely that the police would’ve been called as it wasn’t a matter then - and afterwards - that would’ve concerned him. The subsequent discrimination legislation, hurried through after cases like these and in Smethwick, made it a civil matter.

No, the interesting thing to note is the black customers, Browne, Brown and McFarlane, had the type of professions that would’ve led them to naturally gravitate towards the saloon bar. These were a management class but they still had to drink in the public bar even if they were with white contemporaries.

Segregating someone due to class would have been something perhaps they were used to living under the British empire abroad. “They might be thinking of themselves as the kind of people who go to a saloon bar if it was in Jamaica.” Rob says. “[When they’re told to go to the public bar] they are experiencing a re-racialisation of how they understood themselves.”

The protagonists in the fight against the colour bar could’ve been radicalised by this segregation after they unwittingly found themselves butting against a system that publicly discriminated against them.

It’s why it made no sense in the case of Smethwick for publicans to argue that the colour bar was a poverty bar, when non-white doctors, teachers and lecturers found themselves discriminated against.

Angering anyone - especially learned people - is a mistake as they can mobilise against you. Hawes now had a choice to capitulate against protestors or seek help from people sympathetic to his cause. The far-right were more than happy to help him.

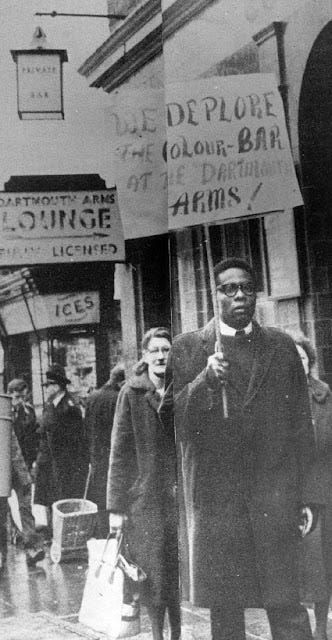

Friday 11 December 1964 - “Silent, grim-faced demonstration on Saturday afternoon.” Banners held saying “If you drink at the Dartmouth Arms you support colour prejudice”. The police were on hand to arrest anyone for creating a disturbance. Future Labour MP and child welfare campaigner Joan Lester was present.

“This picket is stage 1 in getting the ban removed,” said Roy McFarlane, 33, sec of the International Brockley Fellowship Association. “We will not call it a success until the ban is removed. If the ban is not removed stage 2 might be for us to stage a ‘sit in’ but I cannot confirm that until the committee decides.

“The demonstration has been peaceful as we planned it that way. People keep asking us when the fireworks are going to start but we do not want any fireworks.”

West Lewisham Conservative party supported the picket in practice but left it to individual members to choose to join them. In 1965, local fascists pledged support for the Dartmouth Arms’ colour bar.

The matter truly came to a head when the mayor of Lewisham, Tom Bradley, visited with Melbourne Goode, vice chairman of the International Brockley Fellowship Association in January 1965. Both were refused service by Hawes with Lewisham council condemning the segregation at the pub.

In 1965, Britain’s first Race Relations Act (a year after the the US Civil Rights Act) it was made illegal to discriminate against non-white customers. It made discrimination a civil matter, though, not a police matter meaning segregation did continue in some venues, like this one, until the 1990s.

Rob has found evidence of publicans aligning themselves with the far right but extreme groups being involved with pubs was far more ‘widespread’ because they saw cases like the Dartmouth Arms as an opportunity.

There were other colour bars but this was one that exploded in the media - with two sides that were happy to talk to the press. The calm, assured campaigners and the hapless Hawes.

“The far right,” Rob says, “were generally not supported by newspapers - they were seen as rabble rousers and uncouth people. But it doesn’t mean local papers were embracing racial harmony and multiculturalism. [The newspapers’] racism just operated in a different way and the public/saloon bar was part of it.” It was a part of it in that a colour bar could be pitched as ‘we’re still serving non-white drinkers’.”

Hawes cowardly claimed it was his customers who didn’t want to drink with non-white patrons and when the pickets took place he claimed he had a “roaring trade”. But what’s interesting is how sympathetic a press Hawes gets when interviewed despite his spurious claims - at the time a lot of people found the local press itself racist.

“[Hawes’ and other racist justification] is a kind of ‘kidding themselves’,” Rob says. “This was the conclusion I came to when reading justifications [of racism].”

What Rob says is Hawes is being half honest and saying it’s his customers who are prejudiced but not acknowledging he is in the same orbit as them. And to conclude, this is why it’s important to report the mundanity of people like Hawes because racism isn’t always at the extreme end of criminal violence.

“If we only expect racism in the form of the far right,” Rob says, “with people frothing in the mouth, swearing and using racial slurs then we miss the ways that it operates when the people perpetuating it don't even really recognise that they're doing it sometimes, or can excuse themselves from it.”

Today, the Dartmouth Arms is home to Meat Liquor, apparently the only pub where you can buy a fast food fantasy, according to its garish website. The saloon/public bar pub signs remain but little is present to give a clue that this site is an important part of Lewisham social history.

Like the New Cross Fire and the Battle of Lewisham, it changed how we perceive south London and how the black people and their white allies involved fought for a less racist world.

Rob sums it up when he says the Dartmouth Arms became a cause where “people rallied for different versions of the future”.